In his newest book, postChristian, fellow Patheos blogger Christian Piatt takes up some important questions about Christianity in the 21st century: Because Christianity “is not what it should be, what it claims to be,” Piatt asks: What’s left? Can we fix it? Do we care? He frames his reflections on these subtitle questions using seven vices (deadly sins, if you will) and seven virtues associated with the tradition, suggesting in part that for each vice and scandal that humans living in and through the church confront, there is a corresponding virtue and message of good news and grace.

In his newest book, postChristian, fellow Patheos blogger Christian Piatt takes up some important questions about Christianity in the 21st century: Because Christianity “is not what it should be, what it claims to be,” Piatt asks: What’s left? Can we fix it? Do we care? He frames his reflections on these subtitle questions using seven vices (deadly sins, if you will) and seven virtues associated with the tradition, suggesting in part that for each vice and scandal that humans living in and through the church confront, there is a corresponding virtue and message of good news and grace.

It’s honest, accessible, and compelling. It opens up conversation about the meaning and purpose of church and Christian life in a way that invites believers as well as the disaffected into dialogue. But I’m stuck on something. The vice and scandal of postChristian is its complete lack of attention to gender and sexism. How can we possibly hope to fix whatever is left of the Christian tradition and its churches without addressing sexism? Without women’s voices meaningfully present in the pages of a book hoping to do so?

I counted. Eight women (other than a few biblical women) are named in the book’s 206 pages. One is Piatt’s wife Amy (actually, I might want to read a book that she’d write) and another is his aunt Sandra. Sherry Turkle, Anne Lamott, Brene Brown, Hanna Rosin, Kate Bowler, and Heloise (she the beloved of Peter Abelard). That’s it. In a book where names practically fall off the page, from the classical to the contemporary. Constantine to Louie C.K. John Calvin to John Piper.

One chapter that might have actually substantively addressed sexism and gender, the one on lust, is about abstinence, sex addiction, and pornography. Men’s stories. Fine stories, instructive and relevant to the points that Piatt is making, but only a small part of a much bigger, richer, and more complex picture.

Christian theological discussion of sin as pride that doesn’t take account of the classic feminist critique of that model as reflective of men’s experiences alone is simply incomplete. Piatt’s chapter on pride makes that mistake through its sin of omission. He calls for Christians and the church to “lay ourselves bare” and “look at the path of service, humility, and radical openness to which Jesus leads us.” For people who have fully and over-developed senses of self, yes. Indeed. Humble yourself and serve your neighbor. For those whom our culture repeatedly humbles without their consent and expects to serve a master, no. No.

And when it comes to contemporary discussions about women’s experiences with sexism in the church, especially those seeking to lead through various Christian denominations ordination practices, I refer you to Sarah Sentilles’ 2012 book A Church of Her Own.

As Piatt models, however, for each vice and scandal there is grace and virtue sitting nearby. His sin of omission can be partially corrected by some of the virtue in his work. He says “I care more about the lives we’re choosing to live, as individuals, as members of society, as churchgoers, skeptics, seekers, doubters,” than about beliefs or dogma or labels. And as he relates through many personal stories, it seems that Piatt lives a life seeking justice for gay and lesbian people who have been harmed by this church, embracing doubt and questions and human failings, recasting millennia-old traditions so that they might have relevance and meaning today.

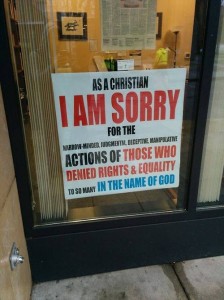

Additionally, I have a colleague who says you can tell a lot about a man by the woman he chooses to marry. In this way, Piatt’s stories about his wife Amy’s ministry, including her public apology-for-narrow-minded-judgemental-deceptive-manipulative-actions-of-so-many-in-the-church sandwich board (based on this postProp 8 billboard) worn around the Portland Gay Pride Fest make me respect his work more.

Additionally, I have a colleague who says you can tell a lot about a man by the woman he chooses to marry. In this way, Piatt’s stories about his wife Amy’s ministry, including her public apology-for-narrow-minded-judgemental-deceptive-manipulative-actions-of-so-many-in-the-church sandwich board (based on this postProp 8 billboard) worn around the Portland Gay Pride Fest make me respect his work more.

So in a good many ways, Christian Piatt gets gender justice and lives into it. Yet if you aren’t naming it, you’re making the sin of omission possible for too many others. If you who ‘get it’ aren’t weaving women scholars and pop culture figures as sources into your book, how can we expect those who don’t ‘get it’ to see that there’s still a problem? The concept of postfeminist seems to linger in the background here, the erroneous belief that at some point in the recent past, we fixed sexism and don’t really need to talk about it anymore. In many churches, this takes the form of believing that if we ordain women, we’re good on gender.

Maybe not. I invite Christian Piatt to apply his own typology of “four responses” to injustice and inequality to gender justice in the church, to sexism and women’s inequality in society, and to interrogate his own work individually.

-

Freely giving time and material wealth toward a cause (here, the cause is women’s equality).

-

Working for systemic change to rectify imbalance in existing systems (here, the imbalance is seen in women’s inequality).

-

Identifying and confessing the complicity we have in being a part of corrupt systems (here, complicity with androcentrism and patriarchy).

-

Actively seeking to subvert the system entirely, acknowledging that it is inherently built on a set of values that perpetuate injustice. (p.119-120)

The key, as Piatt notes in his analysis of churches responding to injustices like poverty, is that 1 & 2 are not enough. He shows that for churches themselves, doing the first is relatively easy. The same can be true for individuals. The second is also possible if one is civically minded and engaged in institutions like the church as well as politics. I can see how Piatt himself is probably good at the first two when it comes to gender justice. I’d like to see more evidence of the latter two in any book that proposes to advocate for a future of any sort of church.

This ultimately matters because it bolsters some of the proposals in postChristian. Because if any part of the answer to “can we fix it?” is yes, then gender justice will need to be part of the solution.

Image via.