‘The Book of Jokes’ by Momus

The Book of Jokes

A Novel

Momus

Dalkey Archive: 200 pp., $13.95 paper

Jokes are a genre of fiction, but the best way to deliver a zinger is to disguise it as autobiography. Comedians know this and the good ones transform themselves into quasi-fictional subjects, weaving long strings of jokes into anecdotal memoir. “The Book of Jokes,” a new book by Momus, marries the self-aware comedian to unreliable narrator, joke to plot and filthy humor to experimental fiction.

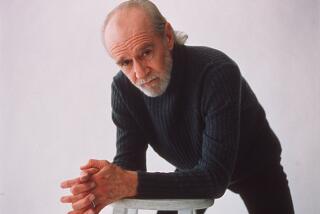

Momus (a Scot named Nick Currie) is known as a prolific trickster songwriter of farcical dream-pop and literary bedroom folk. He also works as a journalist covering design and calls himself a “polymath-dabbler.” “Pop music,” he once said, “was what you could scribble in the margins of literature.” For his novels, Currie continues to use his Momus moniker, suggesting that his fiction is not entirely discrete from his songwriting. This year has seen two publications for Momus: “The Book of Scotlands,” an amorphous fiction concerning “solutions” for alternative Scotlands (its subtitle is “Every lie creates a parallel world. The world in which it is true.”); and “The Book of Jokes,” which is somewhat more novelistic and understands its own parallel worlds by way of the old-fashioned joke.

In “The Book of Jokes,” a nameless protagonist retells his family saga, in which everything that happens to the family is the premise of a joke. His uncles, for instance, are “[t]he Englishman, Scotsman, Irishman and the Welshman.” In the way that Robert Coover and John Barth reinterpreted fairy tales and American urban myths in their fiction, Momus uses the folklore of humor.

Also like Coover and Barth, Momus enjoys his postmodern self-reflexivity. The narrator tells his joke-stories while in prison as a way of postponing his own death at the hands of two inmates named Murderer and Molester, who, he explains, “were hated men, but they hated me more.” He compares himself to a modern Scheherazade (recalling Barth’s “Chimera”), the type of storyteller who knows that she is using seductive narrative as a tool for deceit. Momus writes that, like a used condom, “a used character from a joke is something pathetic and sad, the kind of thing you find abandoned in a forest whose trees are draped with polyethylene bags.”

The condom metaphor is just a tepid sampling of Momus’ in-your-face humor, with most of the book’s story lines orbiting around taboos, including scatology, pedophilia, bestiality and talking, chess-playing penises. One of the book’s central conflicts poses the question of whether two men can be each others’ uncles, which can be answered only with some of the most lurid, labyrinthine incest in literature.

Still, Momus’ book is funny -- sometimes laugh-out loud, sometimes wincingly -- and the humor is delivered in Joycean puns, dry British parody and spoof: “Will I be able to play the trumpet after the operation?” a man asks a doctor. “Certainly,” the doctor says. “That’s wonderful,” the man says, “because I can’t play it now.”

The book is less a single narrative than what it says it is: a novel-in-jokes, an episodic account of the joke’s ability to grab attention and flip expectation. Even on the level of the sentence, Momus constructs setups and twists: “It was a snowy night in late June and milk was spilling from the broken world’s murdered head.” He shows his love of the one-liner with evocative language nuggets, and he stretches two-line jokes into full stories. Less successful are the chapters of bing-bang-boom joke trains that move at the campy pace of sitcoms. But then again, Momus wants people to despise some of these jokes. He knows that the best way to pull readers into one of his parallel universes is to shove them out of their comfort zone and into a zone of shocked disbelief. What could do that better than a 200-page-long tasteless joke?

Simonini is interviews editor at the Believer.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.