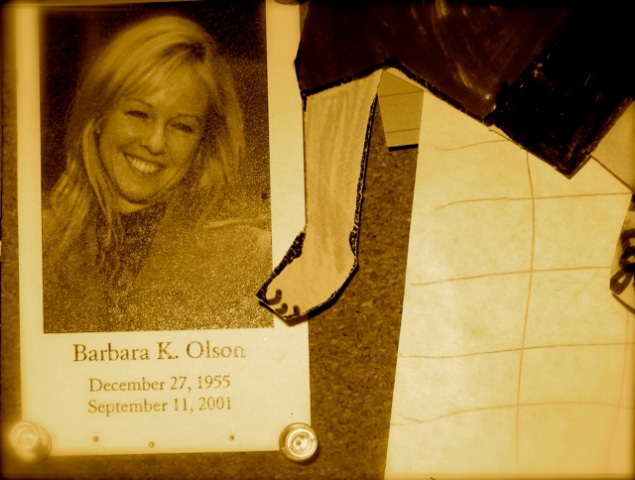

On my kitchen bulletin board is a 2" X 4" photo of a beautiful blond woman flashing a radiant smile. Sometimes the photo goes missing under a school notice or a temporary "art installation"--but the photo is never removed. It was first pinned up eight years ago on our old bulletin board; it resumed its position on our new one, immediately after we renovated our kitchen.

It was only during the past year that my youngest child, Beatrice, now seven, asked after this otherwise total stranger who peers out from amongst the detritus of our family life.

"Barbara K. Olson." She sounded out the words below the photo slowly but with the pride of an improving reader. "December 27, 1955. September 11, 2001."

"Mom," she asked, "why are there dates on this photo? Who is she? Why is she on our board?"

Over the years I've wondered how long it would take for Bea to ask about 9/11. Her two elder siblings--Miranda, now 18, and Nathaniel, 15--lived through it in the harrowing, close-up way so many others in New York and Washington did that day. They were both students at a Jewish day school in a near-in suburb of the capital, about a 20-minute drive from our home. Their father at that time worked in the White House. Barbara Olson was on the plane that smashed into the Pentagon. The students were herded into the main gymnasium and told what was going on--or rather, as much as anyone knew at 10 a.m. what was going on. Miranda found herself trying to console a weeping girl whose father worked in the Pentagon--while wondering about the status of her own father. Had the White House been hit? Would it be? Who knew?

"Barbara Olson was a very good friend of ours," I answered Bea. "She was killed--"

"How?" would be the next question, I knew. And what was I going to say? Bea has no idea how intimately her pre-natal existence and early infancy is tied up with 9/11, at least in my memory. My last photo of Barbara was taken on our back porch, in the summer before the attacks; we are sitting with a group of female friends. You can just see the curve of my pregnancy under a coral blouse. Everyone was "tanned and relaxed" as they say, like those lounging hotel guests photographed during the summer of 1914.

On 9/11, Nathaniel was the same age as Bea is now--so astonishingly young to witness, as we did together, the live footage of the second plane hitting the tower. My mother had called me, screaming to turn on the television. Nathaniel was home from school feigning a stomachache. I didn't attempt to shield him from the footage because...who knew?

"How?"

I hesitated. "In a terrible attack. By terrorists." Bea is old enough to know about terrorists: sinister people in faraway lands whose presence she is occasionally made aware of if she sees the news. But to her they are not vivid, real, and potentially nearby--as they are to her brother and sister. She does not think about them every time she boards a plane. She did not know the Manhattan skyline before its two front teeth were knocked out. She can't remember the orderly buzz of F-16s patrolling the airspace for months afterwards--a buzz that coincided with her 2 and 4 a.m. feedings during her first weeks of life. She doesn't remember the beautiful and vivacious "Mrs. Olson"--nor the hysterical phone call that day from a mutual friend informing me of her death.

Do I want her to? Not especially.

But that's not right either.

A couple of weeks ago, we went to the recently re-opened American History museum. A visiting nephew was in town. Among the war exhibits was a new display of 9/11. Bea and I had just wandered through the first two world wars and Vietnam. My son and his cousin lingered behind, interested in absorbing everything they could. Bea tugged on me impatiently whenever I paused: She'd already "done" the First Ladies dresses and was keen to go see "the big flag." War, I'm afraid, bored her.

But in the 9/11 exhibit, I insisted she stop and look. "Remember you asked me about Mrs. Olson--the woman on our bulletin board?"

"Yes."

"This exhibit shows the attacks in which she was killed. The terrorists attacked New York City and Washington. See those flaming towers? They were taller than the Empire State building but they are gone now. That's why you hear about wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. We are fighting people who would want to do this to us again. And who did it once. We don't want it to happen ever again."

Her little face was solemn. I did not point out that the terrorists' missiles of choice were commercial airliners filled with passengers like her: no need to download that new nightmare "app" for now.

"That's why I keep Mrs. Olson's photo on our board. So we always remember her. And we never forget what happened."

Her quiet nod indicated that she had no further need to ask,"Why?"