From 537 until 1453, Hagia Sophia was a Christian cathedral, mainly for the Orthodox church and briefly for the Catholic Church. Captured by Islamic forces in 1453, it was stripped and transformed into a mosque until 1931, when it was secularized and began being used as a museum in 1935.

Its full name in Greek means “Shrine of the Holy Wisdom of God,” a reference to the Logos, the second person of the Holy Trinity, a foundation doctrine of Christianity. Famous for its dome, it’s considered the epitome of Byzantine architecture. Later, Islamic features, such as minarets, were added, but the original Byzantine creation inspired the building of domed mosques of a similar style.

Now a UNESCO World Heritage site, Hagia Sophia’s future remains an open question, with debate over whether it continues to be a museum or gets turned back into a mosque. Pope Francis visited it and offered prayers last November, saying:

Contemplating the beauty and harmony of this sacred place, my soul rises to the Almighty, source and original of all beauty, and I ask the Almighty to always guide the hearts of humanity on the path of truth, goodness and peace.

On Wednesday, Feb. 25, at 9 p.m. ET, on PBS stations (check local listings), “NOVA: Building Wonders” looks at “Hagia Sophia: Istanbul’s Ancient Mystery.” It focuses on understanding how the structure has survived this long, through a dozen devastating earthquakes, and what can be done to prevent any future quakes from destroying this crown jewel of Byzantine culture.

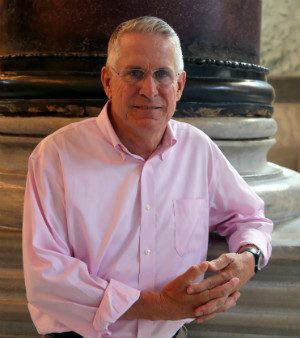

Among the people talking about Hagia Sophia is University of Pennsylvania architectural historian Robert Ousterhout, a major adviser to The Byzantine Institute at Dumbarton Oaks. He’s also the author of many published works, including “Master Builders of Byzantium.”

adviser to The Byzantine Institute at Dumbarton Oaks. He’s also the author of many published works, including “Master Builders of Byzantium.”

Interviewed via email, here’s what Dr. Ousterhout had to say:

Q; Hagia Sophia has been stripped of much of the sacred art put into it by its builders. As an expert in Byzantine architecture, how does that make you feel?

A: It actually challenges me as a scholar. Buildings are forever in the process of becoming — not just buildings like Hagia Sophia, which has seen dramatic transformations throughout its history, but all buildings. This is one of the sources of excitement for a historian like myself. The Byzantine churches of Italy or Greece pose similar challenges, even though they have not witnessed a change of religious usage. For example, Hagia Sophia’s contemporary in Ravenna, San Vitale, had its dome mosaics replaced with a bizarre illusionistic fresco in the 18th century that seems completely insensitive to the original building — and comes as quite a shock to the first-time visitor. The changes in Hagia Sophia are relatively tame by comparison! For me, within Hagia Sophia, the original effect of seven acres of gold mosaic, covering all the vaults, is hard to imagine today. Nevertheless the building continues to inspire visitors of all faiths.

Q: There is talk of the building being again used as a mosque but no mention of it ever returning to its original function as a Christian church. What is the current outlook for the future of Hagia Sophia?

A: My concern is for the building as a historic monument — that it remains accessible to tourists and scholars alike– we have still a lot to learn from the building, and that all interventions in the building follow inter-nations preservation guidelines. For this it is best served as a museum. Buildings have many stories to tell, and to emphasize a single dominant narrative (i.e., the building IS a mosque, or the building IS a church) runs the risk of silencing all others.

Hagia Sophia should be allowed to tell all its stories, to represent all its history. Within Turkey. interest in the building right now is really more political than religious — the potential symbolism of the building is greatly attractive to the the Islamist government. But a building like Hagia Sophia shouldn’t be a pawn in a political struggle, but that seems to be its fate — always.

In 1921 a special service was held in St. John the Divine in New York with prayers in seven languages for the reopening of Hagia Sophia as a Christian church — a heavy-handed symbolic move supported by all major Western powers after the breakup of the Ottoman Empire. This more than anything may have led Atatürk to transform the building from a mosque to a museum. Today, any discussion of reopening the building as a church is moot and only muddies an already complicated issue. The issue of cultural heritage should take precedence over any political agenda.

Q: What, to you, are the most striking and significant features of Hagia Sophia?

A: The sense of spaciousness in the interior is almost magical. While engineers continue to debate the structural system of the building, it is the aesthetic experience that dominates the interior impression — we’re not meant to see the structure, only to experience its seemingly weightless transcendence.

Q: What do you want modern Christians to know most about Byzantine culture, much of which has been overrun by Islamic culture?

This question touches on a very sensitive topic and warrants a complex answer. I suggest reading Averil Cameron’s book “Byzantine Matters,” for additional insight on Byzantine culture.

Q: What are the top five examples of Byzantine architecture that you’d like people to experience firsthand?

A: It’s hard to limit it to 5.

1. Hagia Sophia, of course, for the grandest gesture of Byzantine architecture.

2. The Church of the Chora (Kariye Museum in Istanbul) for a more intimate personal experience, characteristic of later Byzantine architecture. It’s decorative program is well preserved, with both mosaics and frescoes.

3. The medieval Armenian capital at Ani (now in eastern Turkey) for architecture in context — a more dramatic setting is hard to imagine.

4. The lovely little Mausoleum of Galla Placidia in Ravenna. there are other larger churches in Ravenna (like s. Vitale), but this is a real jewel, with the vaults covered with mosaics, forming the starry sky of heaven.

5. The monastery of Hosios Loukas in Greece, near Delphi, for a functioning monastery and site of pilgrimage, with a very elegant church.

And an extra one for fun:

6. The Parthenon on the Athenian Acropolis — it also functioned as a Byzantine church through the Middle Ages, although this is hard to imagine today (and you won’t see it mentioned anywhere on site!)

Here’s a preview: