You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

University of Chicago

New data about time to degree in Ph.D. programs from the American Academy of Arts and Sciences complicate some current reform efforts to help students get through graduate school faster. At the same time, the data suggest that real time to degree is shorter than many people think it is, and that it’s decreasing in some disciplines – albeit slowly.

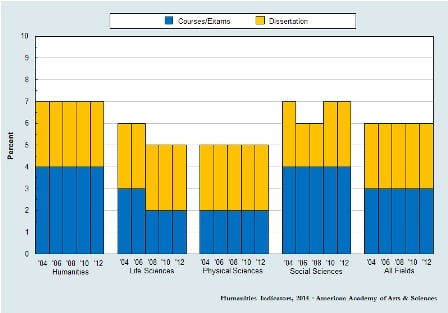

Among the key findings is that the median time is longer in the humanities than in any other field, at 6.9 years in 2012, compared to a 5.9-year average for all Ph.D.s. That won’t surprise anyone following the national time-to-degree conversation, but just where in their studies humanities Ph.D.s are stalling might. It’s been largely assumed that students accrue extra time during their dissertation phase, once they’ve finished their course work, and when their efforts are overwhelmingly solitary and funding is harder to secure. According to the academy’s new data, however, humanities graduate students spend more time studying before starting on their dissertations than their peers in other fields – about four years, compared to two for physical and life sciences students. Social sciences Ph.D.s spend about four years studying, too.

Humanities Ph.D.s also spend less time on their dissertations than their course work – about three years. That’s the approximate average for all disciplines.

Robert Townsend, director of the academy’s Washington office, said in an interview that the course work/dissertation split seemed to be generating discussion Monday among faculty and others interested in the humanities and graduate study. Colleagues outside the humanities seem to find the difference between study time for humanities and other disciplines “mind-boggling,” while colleagues within the humanities worry that the finding "undermines the current focus of various reform efforts,” such as shortening dissertation time and using coursework to prepare for a variety of career possibilities.

Of course not all discussions about shortening time to degree in the humanities involve the dissertation stage. Important questions about streamlining coursework, or “coverage,” also have been asked, including in the Modern Language Association’s recent report recommending that universities develop five-year plans for students and try to guarantee funding all the way through.

Russell Berman, professor of comparative literature and German studies at Stanford University — which has been a national leader in the five-year humanities Ph.D. movement — led the task force that produced the MLA report. In a formal response to the new data, which was published by the academy, Berman praised the findings as clues to the larger puzzle of reducing time to degree.

“The academy’s figures provide some useful clarification,” Berman said. “While the median time spent on the dissertation in all fields is fairly constant — three years — there is noticeable variation in the time required to complete course work and examinations.... If humanities departments could reduce the time required to complete the pre-dissertation phase to the median in all fields or, more ambitiously, to the two years required in the physical sciences, the recommendation in the MLA report of Ph.D. completion within five years would become attainable: two years for course work and exams plus three years for the dissertation.”

Reaching this goal, he added, will require “effective coordination of curriculum with examinations, as well as sufficient funding to support graduate student progress.”

Other commenters were more critical of the data. In their response, Harriet Zuckerman, professor emerita of sociology at Columbia University, and Sharon M. Brucker, coordinator for the Survey Research Center at Princeton University, criticized the study’s methodology and said it feeds into a kind of “fast finisher” bias in academe. They also said there are fundamental differences to courses of study in the humanities and physical and life sciences that don’t come across in the numbers.

“A cursory look at the published Ph.D. requirements by five universities in physics and history provides clues to why fields differ in time spent in course taking,” they wrote. “Some physics departments do not specify any course requirement; others require a minimum number, e.g., four to six courses. Some allow proficiency to be demonstrated in lieu of courses..... By contrast, history department requirements are heavy and specific. Two or three courses are required each semester; completion of research and seminar papers and mastery of two or more languages are routine; exams and dissertation proposals are often expected by the fourth to sixth semesters.”

Zuckerman and Brucker also said that excessive dissertation writing time remains a problem, regardless of the new data.

The academy picture is based on a custom tabulation from the Survey of Earned Doctorates for the Humanities Indicators project. The survey itself includes data about 50,000 new Ph.D.s annually, and tracks such information as time to degree, funding and job prospects. It’s sponsored by the National Science Foundation and other federal entities.

New data reflect the time students spend in the program that confers their degree, instead of published calculations from the Survey of Earned Doctorates that only record time since finishing undergraduate studies and time since start of the graduate studies at any institution and in any subject.

Townsend said that methodology provides a slightly more accurate and optimistic look at time to degree than the other, more common metrics — which put average time to degree for the humanities at eight years or more. He acknowledged that earning a humanities Ph.D. may well require more course work, to fulfill a foreign language requirement, for example. But he said that even though reducing Ph.D. programs to five years still poses lot of challenges, and its ultimate success remains to be seen, a seven-year starting point makes it at least more "attainable."

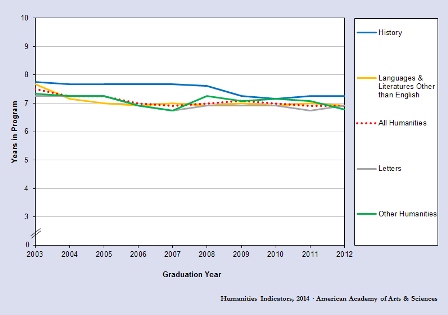

Other data show that reforms already in place might be working; there's been a slight decline in over all humanities time to degree since 2003, when it climbed to above seven years -- even by the more modest metric. Even history, which has been and remains the most lengthy humanities Ph.D., at 7.2 years in 2012, is seeing reduced time to degree.

James Grossman, executive director of the American Historical Association, said he didn't find the difference between time to degree for history and literary studies, the next-longest discipline group, to be "significant," at about three or four months. And he, too, said the course work dynamic may be more complex than mere data let on.

"In many [science, technology, engineering and math] disciplines, graduate students move quickly into a lab and their dissertation grows out of their work in that lab," he said. But that's less true in the humanities and social sciences, "where students are more likely to be thinking more broadly for a longer time, and moving to a dissertation topic only after their qualifying exams."

Grossman also said the data on time to degree needs to be paired with data on how students pay for their doctoral studies, and he cautioned against "reflexively" suggesting that a program is too long. "Seven years might be required to do it well, and there's nothing wrong with that, per se, if the university can provide opportunities for graduate students to support themselves," he said.

Cheryl E. Ball, an associate professor of digital publishing studies at West Virginia University who has published career advice columns in Inside Higher Ed, said she would have chalked up the time delay to both coursework and dissertation, due to "lengthy archival work required of many humanities-based fields" and "students’ inability to focus on a research question."

But, she said, via email, "I think humanities students in the U.S. take a lot of needless coursework, and it does often extend out into their third year, if they are going full-time. I am more and more becoming a fan of the European and Scandinavian (and elsewhere) models of Ph.D. work in which students propose a research project as part of their Ph.D. application and then work in cohorts, research groups, or with their advisers to follow through on those projects."

She added: "I mean, not everyone needs an entire semester of Foucault, for instance, to write their humanities dissertation."