The World’s Most Intense Fitness Program

When a longtime triathlete took on a Kokoro camp—a beyond-extreme fitness challenge modeled on the Navy's Hell Week for SEAL candidates—his first question was purely about the pain: Can I survive this? The second was more metaphysical: Should I even want to?

Heading out the door? Read this article on the Outside app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

I was a multisport burnout, searching for a new challenge, when a Web trawl served up a fitness program I’d never heard of: Kokoro Camp, a civilian version of the infamous Hell Week that the Navy uses as a grueling test of the men who hope to serve as SEALs. Kokoro is run by coaches working for a company called Sealfit, based in Encinitas, California. Most of them are active or former Navy SEALs, and for $1,595 they put you through a rugged training regimen that’s spread out over three days. In exchange for your effort and money, you’re promised a painful, supremely difficult, and ultimately transformative experience.

“Kokoro Camp is designed to help you discover the deep power of your resilient spirit over your mind, and your mind’s control over your body,” the Sealfit site explains. “You’ll be pushed to your limits, because that’s where the biggest breakthroughs happen. That’s also why this is not ‘something you try.’ … You must have a deep and powerful reason for attending this camp, and be ready to pay the price for the ultimate freedom you’ll gain by the end.”

It sounded menacing, if a little out there. Later I learned that a friend who lives near my hometown of Palo Alto, California, Greg Amundson, had done a Kokoro in 2011. Amundson is locally revered as a CrossFit god, but he’s also a former SWAT team member and a retired officer with the Drug Enforcement Administration. He told me, emphatically, that Kokoro is for real. “Brother,” he said, shaking his head, “it’s legit.”

I’d been drawn to the camp because, after a quarter-century of running marathons and triathlons as an amateur, I was bored. My last triathlon had been Ironman France, which I did in 2005 when I was 43. Climbing into the mountains and pedaling through the medieval villages of the Côte d’Azur was a treat, but the 26.2-mile run consisted, in part, of a series of three-mile out-and-backs on the Nice promenade—a treadmill next to the Mediterranean. With a gimpy foot and a bad sunburn, I lurched over the finish line of my fifth Ironman. I shrugged and considered what, if anything, was next.

Over the past ten years, two divergent offerings have been added to the menu of come-one-come-all endurance events. The first is a rebranding of traditional road races into mobile parties and moveable feasts. The Rock and Roll marathon series features live bands at every mile and luxurious VIP tents. Then there are the Hot Chocolate races—fondue awaits you at the finish line!—and the so-called happiest 5K on the planet, the Color Run series. Every half-mile or so, you’re doused with Hippie Powder.

In the other direction are the sufferfests: obstacle-course events, all barbed wire and blood, like Spartan Race and Tough Mudder. Roughest of all is a brand of extreme endurance challenges that aren’t races at all, modeled instead on rigorous military training. Goruck Selection, created by a former Green Beret named Jason McCarthy, is a nonstop, two-day beatdown that involves heavy load-carrying and endless rounds of calisthenics. Kokoro Camp, created by a former SEAL, 51-year-old Mark Divine, is a similar composite: intense physical and psychological torment compounded by exciting extras like sleep deprivation and full immersion in ice-water baths.

As I realized when I learned more about Divine, pain and sacrifice had definitely been transformative for him. In the 1980s, he was a mild-mannered Wall Street accountant with soaring career prospects. But he wasn’t happy with his life, so he took up Seido karate to stave off the drudgery, earning his black belt. His teacher used a memorable phrase during a class—“One day, one lifetime”—and that was it. In 1989, Divine chucked his job to try out for the SEALs. The move shocked his family and his boss, but Divine was never happier. He served six years of active duty as a SEAL, then downshifted to the reserves. In 1996, he opened a brewpub near the SEAL training base in Coronado, California. In 1997, he bought the URL navyseals.com and started an e-commerce business selling tactical clothing and gear.

[quote]The guy below me was worse off, groaning as if he was being crushed. Cerrillo paused for a beat and listened to the pain, then leaned into his megaphone. “This is what you paid for, you idiots!”[/quote]

A crucial moment for Divine occurred in 2004. He was studying yoga in Encinitas—while pursuing a Ph.D. in leadership studies—when he was called up and sent to Iraq. During a C-130 flight into a combat zone, Divine felt nervous. He found space next to a cargo net and started doing sun salutations and deep-breathing exercises, provoking odd glances from a Marine general who was also on board.

While stationed in Baghdad, Divine would often set aside his M4 and perform 90-minute workouts of yoga, squats, and kettlebell swings—all while the occasional mortar shell whistled overhead. The routine purged the stress of wartime, focused his mind, and drenched him in sweat. He knew he was on to something.

Divine went into the fitness business in 2006, leasing an office building in Encinitas that featured, in a central plaza, what he calls the grinder—a small, old parking lot that he uses to grind athletes down with brutal calisthenics. Divine began playing with the mind-body ideas that eventually became Sealfit, and that same year he put on his first intensive camp. The idea was to create a setting where people can experience kokoro, a Japanese word meaning, roughly, “the merging of heart and mind into spirit.”

The Navy’s Hell Week happens early during a SEAL’s training and lasts five and a half days, with round-the-clock physical exertion. Candidates are permitted only four hours of sleep the entire week. The purpose is twofold: to wash out all but the most committed men and to build strong loyalty to the team among those who survive it.

“Kokoro Camp is different than what the Navy does,” Divine told me. “Navy training is designed to find the few who already have the mental toughness needed to become a SEAL. The purpose of Kokoro is to help you reach a psychological benchmark of what is possible.”

As with SEAL training, Divine says, chances are good that you won’t make it. But if you do, you’ll have passed into a different mental and physical realm. Or, as he puts it: “Life after Kokoro just gets easier.”

Kokoro campers are expected to have met rigorous fitness standards before signing up—for example, you need to be able to march 20 miles with a loaded pack in under six hours. Even if you exceed these, Divine says, his coaches will find a way to push you to the point of breakdown. Every attendee is forced to rely on teammates. “No one gets through Kokoro alone,” he says.

Derek Price, a former Detroit Lion who started doing Ironmans after he retired from the NFL, did a Kokoro in 2010. “I couldn’t believe what they were putting us through in the first hour,” he recalls. “I thought for sure it had to let up. It never did.” I ask Price if the camp was as hard as playing pro football. “Kokoro was the hardest thing I’ve ever done,” he says.

“We had eight people enter our first camp in 2007,” Divine says. “Most were special-ops candidates.” The original camp was downright wimpy compared with the show he puts on today. “I didn’t know how far we could push the envelope,” he says. “Every camp, we turned the dial up a bit more and pushed harder and harder.”

Word of the camp spread beyond the armed forces. People with no military aspirations began to trickle in, and Divine started offering five Kokoros a year. As the participants kept coming, with roughly 40 men and women per camp, the ratio tilted toward civilians. These days, only one in five campers is from the military. The rest are CrossFitters, business people, and endurance freaks in search of something else.

For me, identifying that something else was a puzzle. Divine emphasizes that if you’re going to do a Kokoro, you have to have your “why” squared away. Obviously, I had no plans to become a SEAL—at 50 I was two decades over the age limit. Bragging rights can be a motivator for doing a marathon or an Ironman, but nobody I knew had even heard of Kokoro. As Price would later tell me: “Do Kokoro and no one is going to care. What happens inside you is the only thing that matters.”

[quote]Derek Price, a former Detroit Lion who started doing Ironmans after he retired from the NFL, did a Kokoro in 2011. It was “the hardest thing I've ever done,” he told me.[/quote]

In more than 30 editions of the camp, not once has everybody in a group made it through, and I was told that only a handful of 50-year-olds had managed to succeed. So I had plenty of fearful motivation as I trained in advance of my Kokoro, which happened last June.

I put together a regimen combining CrossFit, distance runs, and what SEALs call grinder P.T.—long sessions of push-ups, sit-ups, burpees, leg lifts, and the like. I also started doing ruck marches—carrying a full pack uphill at a fast pace, with a 35-pound plate thrown in to make it even heavier. I used SealgrinderPT.com to find new workout ideas, like the Fat Angie Sandwich: 25 burpees, 100 pull-ups, 100 sit-ups, 100 push-ups, 100 squats, and another 25 burpees, all with a loaded rucksack on my back.

Over a period of 20 weeks, I burned off about 15 pounds and was feeling strong. In the nineties, I had been fit and fast as a runner—I’d done a 2:38 marathon and a 15-minute 5K—but now I felt like I was in better all-around shape than I’d been since I was a teen.

The thirty-second Kokoro Camp began on a vintage SoCal day: dry and hot, under a cloudless sky the color of faded jeans. I was standing in the middle of Divine’s training compound with 16 other people—14 men and two women—in a two-line formation.

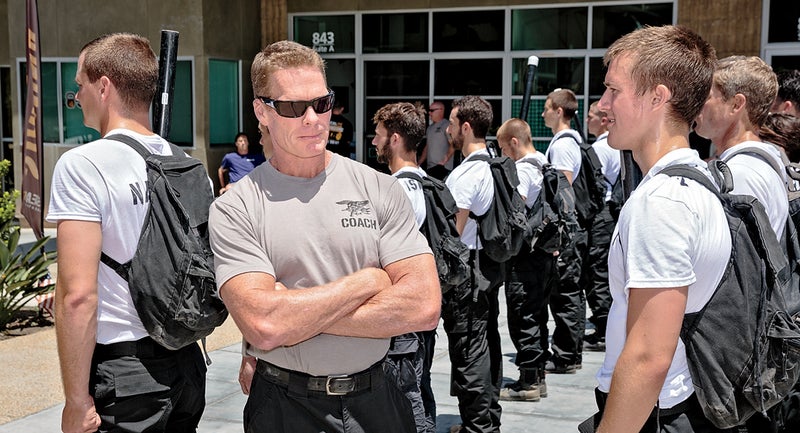

We were wearing white T-shirts stenciled with our last names, black tactical pants, and lightweight combat boots. We each shouldered a black canvas rucksack and carried a dummy rifle—a length of capped PVC pipe filled with sand. We’d just done a one-mile run to the beach and back. We stood at attention, breathing and sweating under the noontime sun as the coaches circled us, doing a remarkable imitation of hammerhead sharks. I counted seven, including Divine, making a two-to-one camper-to-coach ratio.

It was nerve rattling, for sure. Divine, with his military flattop and diamond-cut features, is built like a decathlete, scorched of body fat and radiating a potentially violent combination of speed and power. He spoke quietly and encouraged us to breathe deep and slow.

I didn’t see him walk away, but suddenly a coach named Dan Cerrillo* stood in his place and started cursing through a megaphone. Cerrillo is a square-shaped former instructor in the Navy’s BUD/S program, the punishing six-month training course that transforms recruits into active-duty SEALs. In SEAL-speak, Kokoro is broken up into segments called evolutions. The first evolution is called a breakout, and it’s meant to create the kind of panic and chaos that combat does.

Cerrillo used his megaphone to share his thoughts about what spoiled candy-asses we were. “You idiots!” he yelled. “You don’t need to buy a new plasma TV! You don’t need a new car! You are stupid sheep that I and others like me have to risk our lives to protect.”

He had us drop on our backs and hold our feet six inches off the ground. Before long I got a bucket of water dumped on my face, and it went into my sinuses. During the foot raise I held out longer than some, but after about four minutes I gave up and my heels hit the ground. A different coach put a megaphone to my ear and whispered, “There’s nowhere to hide. We see everything.”

We were then ordered to build a cabin using our bodies as the logs. I was on the second layer off the ground. As the others climbed on, somebody’s forearm jammed hard into my throat. But the guy below me was worse off, groaning as if he was being crushed. Cerrillo paused for a beat and listened to the pain, then leaned into his megaphone.

“This is what you paid for, you idiots!”

The main lesson from Kokoro is this: teamwork is superior to individualism. That idea is central to the SEAL code of conduct, but it didn’t come naturally to me. Teamwork is contradictory to the time-trial nature of an Ironman, and the very notion of racers helping other racers—by drafting one another during the bike leg, for example—is forbidden by the rules.

Divine thinks the lone-wolf style is too easy. “Training with others makes you accountable to others,” he told me. The ideal mindset is to feel like a member of a team on a mission. You aren’t caught up in your own drama; instead, you’re focused on helping the buddy next to you.

In my preparations for Kokoro, I mostly trained by myself, aside from a few visits to a CrossFit gym in Palo Alto. Looking back, it was a mistake to directly apply what had worked during my preparations for solo races. As Divine warned, I should have found others to train with and arrived with a firmer sense of why I wanted to do a Kokoro. I didn’t, and I got in serious trouble on the first afternoon.

At around two o’clock, we were broken into teams of four and given a 250-pound wooden log to lift, as a group, over our heads. Then we circled a 600-pound tractor tire and lifted it to our chins. The coaches thought our lifts looked sloppy, so they made us do it more than a dozen times. To put more force into my lifts, I was contorting my back like a rabid dog, but I could feel myself fizzling. There was no sign of a break coming soon. A two-word daydream wafted through my mind: Snickers bar.

Later, I found myself alone in the parking lot, lugging 53-pound kettlebells in each hand as several coaches stood side by side, egging me on with abuse. One told me to farmer-carry the bells to the gym; another hollered at me for not bringing them to him. I was running toward the gym when things went black and I passed out, still carrying the weights and going down hard.

I came to moments later and was guided to a bench in the shade. My heart registered 70 beats per minute, apparently a sign of low blood sugar. I downed two cartons of Muscle Milk and rejoined the others on a march to the Encinitas beach. Single-file, we moved down a wooden staircase, passing beach-goers who seemed to wonder why a paramilitary unit was doing drills in a town known for surfing and yoga. Descending the steps, we were teased by a light ocean spray and the sparkling aquamarine waters of one of the area’s prime destinations.

First up for us was “surf torture,” in which you lie down in the shoreline breakers and get whapped in the face. Then we swam out far enough that we had to tread water. After about an hour of this, I was struggling to stay afloat and slurring my words. I was ordered back to the beach.

Sitting under a sandstone bluff, I watched campers come out and fireman-carry each other across the sand. I pondered my status. Kokoro coaches reserve the right to drop a trainee for performance problems, but no one had said anything. They were leaving it up to me. If I decided to quit, I would have to own it all.

So I did quit. I hated to, but I worried that I was taking a serious risk. The only thing the Sealfit doctor offered was sarcasm, suggesting that I hadn’t trained right. On the way back to the compound, one of the campers, Michael Israelitt, tried to talk me into hanging on.

“We’ll get you through,” he implored, and his generosity hit me hard. We’d only met that morning, yet he was pledging to carry me for the rest of the camp, multiplying his own suffering. I thanked him, saying that, unfortunately, my only contribution to the team would be 185 pounds of dead weight.

Mark Divine offered words of genuine compassion, then said, “You’ll have to find a silver lining.” I stuffed my gear into a duffel bag and unceremoniously walked out of the compound into an alley. The final insult: I couldn’t remember where I’d parked.

I went to the hotel, showered, bandaged my cuts, and ate a turkey sandwich. Then, like some fanboy of pain, I went back to Sealfit HQ to watch the rest of the camp unfold. By the end of the first 30 hours, two other people besides me had dropped out. The coaches rotated back and forth as they kept pushing the remaining 13 campers through epic CrossFit workouts, additional surf torture, and a dusk-to-dawn ruck march on Palomar Mountain.

It was inspiring to watch people tough it out. Danielle Gordon, a 35-year-old local CrossFitter who works in marketing, flew through the camp until early Sunday morning, when she tripped and fell during the Palomar descent, slamming her head. She got no sympathy from the coaches—only a warning not to stew in self-pity. She kept going. Garrett Dietrich, a 32-year-old salesman from Pearland, Texas, suffered what felt to him like an asthma attack, compounded when he got severe chills in an ice bath. He finished the camp wrapped in a space blanket. Peter Feer, a 53-year-old executive coach from Basalt, Colorado, injured both legs on the first day but managed to finish.

And in a moment that won’t be soon forgotten, Jon Hofius, a 27-year-old mechanical engineer from San Francisco, was sitting in an ice bath—after being dunked by a coach named Adam Stevenson—when a blob of saliva and mucus started rising in his throat. His dilemma: Do I spit it into the water or onto the pavement? Which will earn me the lesser penalty?

Hofius chose to burst out of the water and cough the blob onto the pavement. Stevenson’s glare surged with menace, and Hofius figured he’d blown it. So, in a Hail Mary to buffer the coming punishment, Hofius snorted the spit off the ground. It was a rare moment in Kokoro history: a trainee went further than even a coach would have asked.

“I can’t believe you just did that,” Stevenson said.

On Sunday around noon, the group was getting hammered in a final breakout. They were ordered to do 450 burpees—penalty burpees, imposed on everybody because a few campers had fallen asleep during the van ride back from Palomar. Then they were divided into two groups and assigned physical training using logs. Coaches came out with water hoses and buckets. As the campers hoisted the logs over their heads, they got hosed while Cerrillo laid into them. Divine, with his arms folded across his chest, watched carefully from the perimeter. Then he took over the job of yelling commands.

As I watched campers move around under the logs, it was obvious that a transformation had occurred. In only two days they’d become cohesive—there was fatigue in their eyes, but they were working efficiently and in unison. Divine was satisfied with what he saw. “Class 32,” he said, “you are secured.”

It was over, and the 13 campers who made it all the way whooped and hugged each other in euphoric relief. Nobody seemed to care about all the cuts and abrasions on their arms, legs, and backs, their skin ravaged by crawling through thorns and sand.

Divine had told me that when successful SEAL candidates emerge from Hell Week, there is a new look in their eyes, a gleam of inner knowledge. I could see something like that in my former teammates. At long last, I may have found the answer to my original question. Before, when Divine talked about the Kokoro spirit and his belief in an integrated, holistic training program, I was leery, and in the first few hours after quitting, I bitterly pledged never to return. But now I could see what he was talking about and what had been missing for me at Ironmans. There, if things go bad, you just slow down. No such option exists at Kokoro, forcing you to scour the depths for some hidden, stronger self.

But will I actually go back? My plan is to train to a level where I know I can finish—assuming that’s something I’m still capable of. Then I’ll decide.

*The print version of this story misspelled Dan Cerrillo's mame. Outside regrets the error.

T. J. Murphy (@Burning_Runner) is the author of Inside the Box, about the rise of CrossFit.