NASA Finds Ingredient for Plastic on Saturn's Moon Titan

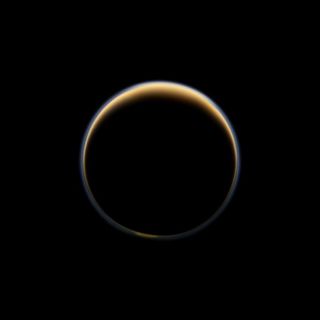

For the first time, a chemical essential for the creation of plastic on Earth has been found in a far-off part of the solar system: Saturn's largest Titan.

The discovery, made by NASA's Cassini spacecraft currently orbiting Saturn, found that the atmosphere of Titan contains propylene, a key ingredient of plastic containers, car bumpers and other everyday items on Earth. NASA scientists announced the discovery with a video describing the propylene find on Titan.

"This chemical is all around us in everyday life, strung together in long chains to form a plastic called polypropylene," Conor Nixon, a NASA planetary scientist and lead author of a paper detailing the new research in today's (Sept. 30) issue of the Astrophysical Journal Letters said in a statement. "That plastic container at the grocery store with the recycling code 5 on the bottom — that's polypropylene." [Amazing Photos: Titan, Saturn's Largest Moon]

Scientists used Cassini's composite infrared spectrometer (CIRS) instrument, which measures infrared light given off by Saturn and its moon, made the discovery.

The new study helps piece together a long-standing mystery about Titan's atmosphere. When Voyager 1 conducted the first close flyby of the moon in 1980, it recognized gasses in the moon's brown atmosphere as hydrocarbons.

Scientists have found that hydrocarbons — which make up fossil fuels on Earth — form on Titan after sunlight breaks apart methane and the chemicals reform into chains of two or more carbons. Voyager found evidence of the heaviest three-carbon hydrocarbon, propane, and the spacecraft also discovered propyne — one of the lightest in the family.

The middle-weight chemicals like propylene, however, were missing from the Voyager data.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"This measurement was very difficult to make because propylene's weak signature is crowded by related chemicals with much stronger signals," Michael Flasar, Goddard scientist and principal investigator for the CIRS instrument, said in a statement. "This success boosts our confidence that we will find still more chemicals long hidden in Titan's atmosphere."

Titan is about half the size of Earth and is the second-largest moon in the solar system — only Jupiter's Ganymede beats it out in size. The moon is also the only one in the solar system that harbors clouds and a planet-like atmosphere, which is mostly composed of nitrogen and methane.

Cassini launched to space in 1997, arriving in orbit around Saturn in July 2004. The mission — centered on understanding Saturn and its many moons — is expected to continue until 2017 when the spacecraft will be crashed into Saturn's atmosphere.

Follow Miriam Kramer @mirikramer and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on SPACE.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Miriam Kramer joined Space.com as a Staff Writer in December 2012. Since then, she has floated in weightlessness on a zero-gravity flight, felt the pull of 4-Gs in a trainer aircraft and watched rockets soar into space from Florida and Virginia. She also served as Space.com's lead space entertainment reporter, and enjoys all aspects of space news, astronomy and commercial spaceflight. Miriam has also presented space stories during live interviews with Fox News and other TV and radio outlets. She originally hails from Knoxville, Tennessee where she and her family would take trips to dark spots on the outskirts of town to watch meteor showers every year. She loves to travel and one day hopes to see the northern lights in person. Miriam is currently a space reporter with Axios, writing the Axios Space newsletter. You can follow Miriam on Twitter.