Everest’s Darkest Year

The true story of the mountain's most horrific day, the Sherpas who paid the price, and the aftershocks that will change the mountain forever

Heading out the door? Read this article on the Outside app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

At 3 A.M., Lhakpa Gyalgen’s alarm went off at Base Camp, but he dozed until 3:07, when Tenzing Chottar rattled his tent fly. “He had been reading holy books and prayers,” said Lhakpa Gyalgen, who is from Thame, in Nepal, and was a lama at Kathmandu’s Kopan monastery before becoming a climber. Tenzing Chottar, 27, grew up in Ylajung, a mile up the Bhote Kosi River from Thame, and had a wife and a four-month-old boy. Lhakpa Gyalgen, 30, also had a young son, a two-year-old born blind. He and Tenzing Chottar lived near each other for most of the year in Kathmandu’s Sambala neighborhood.

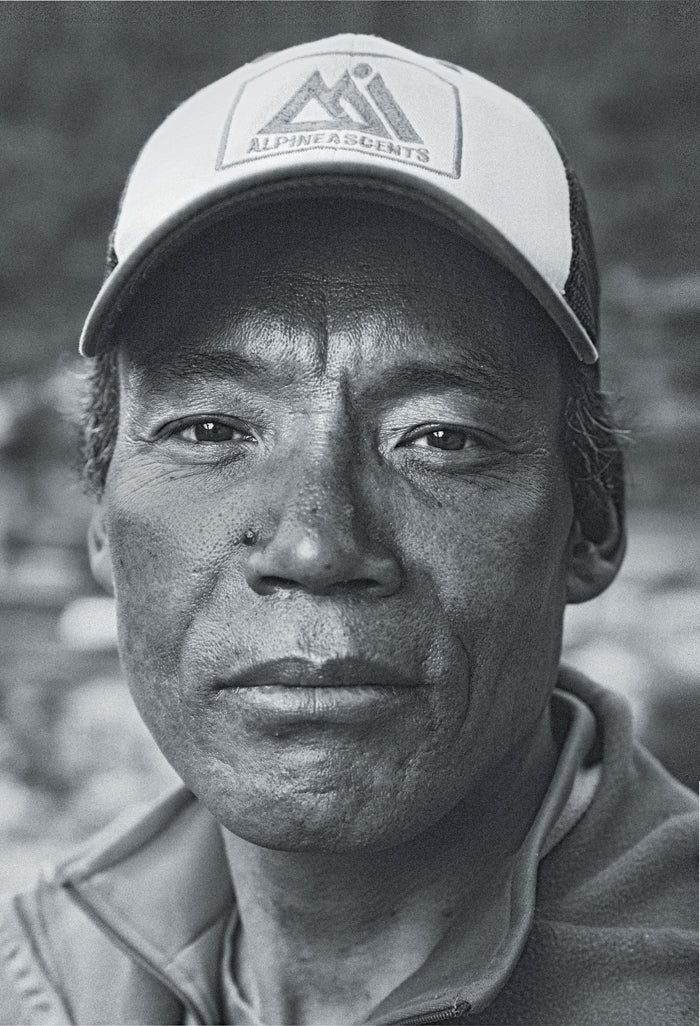

Lhakpa Gyalgen, who is five foot nine, with closely set eyes that have trouble focusing, had worked on Mount Everest for several years, but this was Tenzing Chottar’s first expedition. Physically, he was just right—short, strong, and energetic—but in the Himalayas, there’s no substitute for experience.

“He’d climbed trekking peaks, but he’d never been to the big mountains,” said Lakpa Rita, the longtime sirdar, or Sherpa foreman, for Seattle-based Alpine Ascents International, one of the top guiding companies working the south side of Everest.

The plan was for the two men to stay close on the way up. “Tenzing Chottar was new, but I was new, too,” said Lhakpa Gyalgen. “I have been three or four times, but the first day is always difficult for me. I couldn’t walk well, so we walked together.”

Ten Sherpas clipped to the same line as Dawa Tashi had received fatal, bone-crushing blows, and the avalanche piled them into a stack that became their communal grave.

On that morning, April 18, Lakpa Rita had 27 Sherpas gearing up to carry loads through the Khumbu Icefall, most of them from his home village of Thame—or from one of several other small villages, consisting of a few dozen houses each, that hug the plunging downward path of the Bhote Kosi. For the 2014 climbing season, Alpine Ascents had been hired by the Discovery Channel to provide logistical support for its live broadcast of BASE jumper Joby Ogwyn’s attempt to do a wingsuit flight off Everest’s summit. (Ogwyn himself was to be guided by Madison Mountaineering, launched this year by Alpine Ascents’ former head guide Garrett Madison.) Lakpa Rita also had 12 paying clients trying to reach the top.'

Lakpa Rita—who is 48 and has the small, wiry frame of an endurance athlete—and his younger brother Kami Rita, his chief lieutenant, had long since earned the right to sleep until sunrise: between them, they had 37 Everest summits. Among the men working for them that day was Ang Tshering, who at 56 was the oldest of the crew. He’d been the Camp II cook for more than 20 years and had just completed construction on a teahouse in the village of Thamo for his retirement.

I’d met Ang Tshering on a reporting trip to Thame in the fall of 2012. He’d spoken proudly about the famous Lakpa Rita—“the great sirdar,” he called him, who “rescues on all expeditions, always.” He’d told me how Lakpa Rita had dug out and saved his younger son Mingma that summer, after an avalanche on Manaslu that killed 11 people. For 2014, Ang Tshering’s last season, he had to make just one lap through the treacherous Icefall at the start—up to Camp II at 21,300 feet—and a return trip at the end.

Ang Tshering started out with his son Pemba Tenzing, who is 36, and the younger man quickly moved ahead. Then, from the other outfits in camp, came more than a hundred bobbing headlamps, almost all of them Sherpas converging on the route.

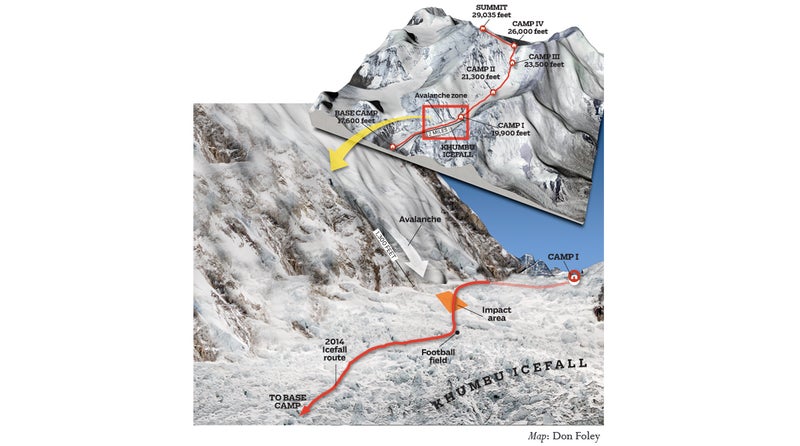

The Khumbu Icefall is the first major obstacle to climbing Everest and one of the mountain’s most relentless killers. Over time, as it migrates downhill from Camp I (19,900 feet) to Base Camp (17,600) at a rate of a few feet per day, the Khumbu Glacier fractures into towering columns, crumbling ice ledges, and deep crevasses that are constantly moving and whose walls are prone to collapsing. Each year, a group of Sherpas known as the Icefall Doctors are hired by Nepal’s government, through the Sagarmatha Pollution Control Committee. The Doctors are responsible for a single, dangerous job: snaking a route through the Icefall, stringing ropes and placing aluminum ladders over the crevasses and up the cliffs.

Rising directly above the Icefall is Everest’s west shoulder, a mile-high face that supports a giant hanging glacier. As that glacier creeps downward, it regularly calves, sending ice blocks rocketing toward the route. In recent years, the route to Camp I has run up the left side of the Icefall, directly under the overhang, because of unstable conditions through the middle.

Around 6:30 A.M., Tenzing Chottar and Lhakpa Gyalgen reached the top of a series of flat benches, at about 19,200 feet, known as the football field, where the terrain begins to roll. A triple ladder, laced together with the ubiquitous cheap Korean rope that lines much of the route, led up an ice cliff to a knoll. On the other side was a descent to two more ladder crossings balanced on narrow ice pillars, where the glacier flaked apart over a 100-foot chasm. Pemba Tenzing was in the first group to reach these ladders, one of which had been damaged by falling ice. The lead Sherpas put down their packs and set about repairing the ladder while a queue of people formed behind them.

“When I reached the spot, people were saying, ‘In the mountains, you have to stand in line, just like in Kathmandu for petrol,’ ” Lhakpa Gyalgen recalled. “They were taking photographs.”

Things were soon moving again, but the backup would take time to clear. There were more than 100 Sherpas strung through the top half of the Icefall, with the majority having already passed the bottleneck. Lhakpa Gyalgen crossed the ladders and looked back. Ang Tshering was on top of the rise, among a cluster of a dozen people, waiting his turn to cross. He waved. Nima, a Sherpa working for Alpine Ascents, was on a ladder taking a photo with his cell phone, and Tenzing Chottar had just stepped off.

At that moment, a quarter of the way up the west shoulder, an ice chunk the size of a ten-story apartment building peeled off and fell. In Madison Mountaineering’s communications tent, Base Camp manager Kurt Hunter was on the radio with his sirdar, Dorjee Khatri. He heard the rumble from above, then a scream over the air, then nothing.

What came crashing down on the men that day was an avalanche only in the sense that it involved frozen water. Beyond that, it more closely resembled a comet.

When the serac calved off, it initially fell as a mostly solid chunk of blue ice. A Chinese client with the outfitter Jagged Globe later analyzed before and after photos of the missing piece of glacier and estimated its size to be 130 feet wide, long, and tall—nearly 2.3 million cubic feet, weighing 64,000 tons. The ice block was roughly 1,300 feet above the route, and by the time it had finished crashing down Everest’s west shoulder, it hadn’t just pulverized—it had detonated, blasting loose scree and even bedrock as it roared over the slope with unimaginable fury.

For the men in the Icefall, there would have been a soul-chilling gap between the sound of the ice block’s release—a solid kerchink, like railroad cars uncoupling—and a brief moment when it actually sailed through the air. Then all hell broke loose as the serac exploded and re-exploded, vaporizing the ice into fine, aerosolized crystals, recruiting new projectiles from the slope below until it resembled a thrumming white cloud of boulders and grapeshot.

As the April 18 disaster unfolded, many of the men—both the survivors and the 16 who died—probably heard a sound like a rolling thunderclap. Others who survived said they heard nothing, but everybody surely felt what was coming. From a distance, a big avalanche on Everest can be mistaken for an earthquake: the low waves produced by the tumbling mass aren’t just audible but palpable. Between the first sound and the final impact, those below had about ten seconds to react.

Lhakpa Gyalgen said he ran uphill “very fast” and grabbed onto Pasang Dorje, another Alpine Ascents Sherpa. The two turned sideways behind a narrow fin of ice that offered some degree of protection. Lhakpa Gyalgen’s chest was sticking out just a bit, and a fist-size piece of ice whizzing past pierced his down jacket and poofed feathers into the air, as if from a shotgunned game bird. The Chinese thermos that Pasang Dorje carried in his pack was crushed by the impact from an ice chunk, but he was unhurt.

“I don’t know how my back was saved,” Lhakpa Gyalgen said later, when I interviewed him in Namche Bazaar. “I had a big bag, inside which I had cashews and rice that I’d offered at the puja,” a religious ceremony held by each team before the beginning of a climb. Four other men who’d cleared the worst of the blast zone—Wongdi, Mingma, Mingma Tshering, and a lowlander named Rakesh—were bruised and lacerated but otherwise all right.

On the mountain, amid the scrum of porters, was a Sherpa named Dawa Tashi, who was working for UK-based Jagged Globe. When everyone else turned away and crouched, Dawa Tashi stood his ground. As he later described it from a hospital bed in Kathmandu, he counterintuitively aimed his chest directly toward the avalanche, taking blows to the torso and head. “I remembered my wife in Kathmandu,” he said. “I remembered my parents. Then I was knocked out.”

At the time of the avalanche, two Adventure Consultants Sherpas, Kaji and another young man named Chhewang, were also getting ready to cross the ladder, behind Nima and Tenzing Chottar. They saw a small overhang next to them, and Chhewang pulled Kaji behind it.

“There was a little hill-like structure that broke off and fell straight down and broke into pieces,” said Kaji, who is from Taksindu, below Lukla, the town where most people fly into the Khumbu region. In the next moments, he likely witnessed the death of either Nima or Tenzing Chottar. “One person ahead of me was blown off the top and thrashed below,” he said. “It was like a thunderbolt. I realized what it was, but there wasn’t a way out. It knocked me unconscious.”

Just below them was Madison Mountaineering’s sirdar, Dorjee Khatri, who was standing at the top of the triple ladder, talking into his radio. The main avalanche hit and buried him boots up. It also knocked loose more ice that killed one of Madison’s Sherpas, Phur Temba, at the bottom of the triple ladder.

In Base Camp, Alpine Ascents’ Michael Horst, a veteran American guide living in British Columbia, had just woken up when he heard the crash and rumble. “I opened the tent door, looked toward the south to the moon, and then heard the initial fall of the avalanche and watched it sweep across the route,” he said. “I realized right away that there was almost no way people weren’t involved.”

Horst ran to Lakpa Rita’s tent and shook the nylon to wake him. Lakpa Rita kept a handheld radio nearby at all times, and he switched it on. When he made contact with Lhakpa Gyalgen, he said, he was quickly told that “a terrible thing has happened up here.”

Horst next roused his Base Camp manager, Joe Kluberton, who would coordinate radio traffic, and U.S.–based guides Andy Tyson and Ben Jones. From there, news spread to a few guides from other camps who frequently assist on rescues, like Argentine Damian Benegas, of Benegas Brothers Expeditions, Rainier Mountaineering’s Dave Hahn, and the crew at International Mountain Guides (IMG), who had several clients and Sherpas on the football field when the avalanche hit. By the time these men had gathered, Lakpa Rita and Kami Rita were already on the trail. Getting from Base Camp to the impact zone involved a hike of 1,600 vertical feet, which at that altitude took Lakpa Rita and his brother 90 minutes to cover.

Up in the Icefall, the surviving Sherpas were in shock but were making rational emergency assessments. The wave of pulverized ice swept over them with a blast of wind, coating every man in ghostly white. The powder cloud stretched across the entire width of the Icefall and dampened any sound waves, producing an eerie blizzard of silence.

Sherpas believe that the spirit lingers close to a dead body for three weeks. Any climber lost in a crevasse is thought to have a restless ghost loitering nearby.

“I was holding on to Pasang Dorje’s bag, so we shook it off and found the radio,” said Lhakpa Gyalgen. “Both of us had turned white with the ice.” They told Lakpa Rita that a disaster had taken place. Their gear had been destroyed, and they needed help.

“I said, ‘Don’t worry about all the gear,’” Lakpa Rita said. “‘Just take care of yourself. If it’s not safe to stay there, move away.’”

The towers that had braced the two upper ladders were now filled in with avalanche debris, but they still contained dangerous gaps. Tenzing Chottar had been swept away, as had Nima, and there was no telling how many others were dead. They moved downhill, over the debris, and back up onto the hill where Ang Tshering had waved at them.

“I saw someone whose body was half in the ice, and vapor was coming from his mouth,” said Lhakpa Gyalgen. Pasang Dorje shouted, “There’s Tenzing!” but it was Dawa Tashi, who was alive and unconscious. They kept moving. Twenty or thirty yards farther down, Lhakpa Gyalgen and Pasang Dorje came to the edge of the cliff that had been served by the triple ladder. “I peeked down and saw the ropes cut. I saw a leg hanging,” he said. This was Madison’s sirdar, Dorjee Khatri.

Dawa Tashi came to on the hill after a few minutes. “There were about ten of us, but when I regained consciousness I was the only one there—with half my body in the snow,” he said. “No one was crying. Everyone was buried.” He was encased in ice and could see in only one direction.

“I cried and shouted, but after no one came soon, I started to dig myself out,” Dawa Tashi continued. “I used my right hand to dig out my left hand.” He tried to stand, but his harness was still clipped into the fixed line, which was buried in debris. He had suffered four broken ribs and a broken scapula.

The area quickly filled with people who had descended from Camp I and from higher up in the Icefall to help. Madison Mountaineering’s Jangbu Sherpa, a 32-year-old who divides his time between Nepal, the U.S., and South America, began to assist Dawa Tashi. “We started digging him out, and he was conscious,” said Jangbu. “He recognized us.”

Lhakpa Gyalgen, Pasang Dorje, and several others still needed to climb down the triple ladder on the back side of the hill, which had also been damaged. A Sherpa named Wongdi, who worked for Jagged Globe and was bleeding from his right ear, slid down the fixed line with his gloved hands and then leaped for the bottom. “When he came down, it created a big sound, and I was very scared,” said Lhakpa Gyalgen. “Some people jumped off, but I couldn’t jump.” Eventually, though, he did.

Kaji regained consciousness higher up, near where the pillar ladders had been, and radioed Base Camp. “I was buried in the snow, hit by the hump, but I wasn’t fully buried like those who died,” he said. His friend Chhewang was panicked but alive. (In a cruel twist, ten days later, Chhewang was killed by lightning back in his home village of Nunthala.) “One guy who was strong carried me on his back,” said Kaji. “It hurt even more.” His rescuer laid him down near the top of the hill, above the triple ladder, where most of the others had been buried. He’d suffered two broken ribs.

As other rescuers arrived, Lhakpa Gyalgen and Pasang Dorje retreated. “I wanted to stay, but I couldn’t, as I was shivering badly,” Lhakpa Gyalgen said. “Others were taking out the dead bodies.”

Within minutes, more rescuers who’d been above the avalanche started to arrive, but as of 7:36 A.M. the trail up to the accident site was still inaccessible from below. Justin Merle and Max Bunce, both from IMG, had been in Camp I when the avalanche hit, and they quickly mobilized and headed down. Lakpa Rita called Ang Tshering’s son Pemba Tenzing and Tenzing Chottar’s brother, Fura Tenzing. He asked them to grab the heavy landscaping shovels from Camp I and hurry down to the avalanche field.

Pemba Tenzing remembers being struck by the sight of abandoned backpacks along the trail. “I only saw bags, a lot of bags, but nobody was there with the bags,” he said. Then he rounded the corner to the impact zone, which was 100 feet wide where it crossed the route. He saw Jangbu Sherpa and several others working to free Dawa Tashi.

By 8:12, Merle, Bunce, and Austin Shannon, another IMG guide, had reached the three most seriously injured survivors. Bunce took charge of the effort to rescue Kaji; Dawa Tashi, who was the worst off, was aided by Merle; another Sherpa, Ang Kami, who worked for IMG and was able to walk to the football field before collapsing, was looked after by Shannon. Kluberton had radioed at 7:57 to let the rescuers know that helicopter pilot Jason Laing, a gruff New Zealander who works for Nepal’s Simrik Airlines, was en route with a long-line-equipped heli but would take two hours to reach them.

“An IMG guide had come with a doctor, and another group brought me oxygen and a stretcher,” said Kaji, referring to Dr. Rob Casserley, who was attached to the expedition led by Henry Todd, a longtime outfitter from the UK. “They put me on the stretcher,” Kaji said. “Some of them were making the helipad”—marking a big H in the snow by pouring out lines of red sports drink—“while some stayed by my side. They gave me warm water to drink. I was shivering, my hands and legs had turned blue. They massaged my hands and feet and gave me new gloves to wear. My body gradually began to warm.”

Just below them, Jangbu Pemba Tenzing and Fura Tenzing finished digging out Dawa Tashi. Beneath him, in the hole he’d just been pulled from, they saw something horrifying and unforgettable: another set of legs. As they uncovered that man, there was another below him, then another, then another. Ten Sherpas who had been standing near Dawa Tashi had all been clipped to the same line he was. They had received fatal, bone-crushing blows, and the avalanche piled them into a stack that became their communal grave. Only Dawa Tashi, who was beaten up but stayed at the surface, survived.

In Base Camp, Kluberton and the radio operators at Adventure Consultants and Jagged Globe were struggling to figure out who was missing. By 8:25, Alpine Ascents knew that five of its Sherpas were unaccounted for: Nima, Tenzing Chottar, Ang Tshering, Mingma Nuru, and Dorji. Adventure Consultants soon reported that it had lost three men (Phurba Ongel, Chhiring Ongchu, and Lhakpa Tenjing) and that one—Kaji—was unable to walk. But it took several more hours for the full scale of the tragedy to become apparent.

When Lakpa Rita arrived at the scene with Kami Rita at about 8:45, Jangbu Sherpa, Pemba Tenzing, and eight or nine others had already found four bodies. The men had only had time to cover their faces with jackets and neck gaiters before they were killed.

Pemba Tenzing began the grim task of identifying his father, Ang Tshering, who was the seventh body found in the hole. “I recognized him by his shoes,” he said later. Once he was certain his father was gone, he decided to leave the scene. “I came back to camp quickly, phoned my mother, and left with money for the monks from Thame.” Sherpas believe that an elaborate funeral, with many displays of devotion, will help lead to a better rebirth for their loved one. Pujas, which are also held after deaths, often cost several thousand dollars.

At 9:09, Damian Benegas, who reached the accident site just ahead of Lakpa Rita, reported that he’d counted ten dead. Before day’s end, the total would rise to 13 confirmed dead, with Pem Tenji, Gurung Ashbadur, and Tenzing Chottar still missing. The others who perished were Ang Kaji, a second Sherpa named Dorjee, Phur Temba, Pasang Karma, and a second lowlander, Asman Tamang. All the men died from either blunt-force trauma or suffocation.

In the slide zone, Horst joined Merle in the task of caring for Dawa Tashi. They packaged him into a stretcher and, on the advice of a doctor in Base Camp, gave him eight milliliters of dexamethasone, a fast-acting steroid that can help trauma patients overcome shock.

At 10:05, after landing in Base Camp and picking up American climber Melissa Arnot, a paramedic, and Adventure Consultants guide Dean Staples, Laing set his heli down in the football field. He retrieved IMG’s Ang Kami, then Adventure Consultants’ Kaji, returning each man to Base Camp helipads before equipping the craft for the long-line rescue of Dawa Tashi, whose perch between two steep walls didn’t allow for a landing.

Once he was in Base Camp, Dawa Tashi received rapid and effective emergency treatment. “The anesthetist began looking after his airway and the head and facial injuries and we cut him out of his wet down suit, got a drip in, gave morphine and performed an abdominal ultrasound,” wrote Adventure Consultants doctor Sophie Wallace on the website Adventure Medic. “He had bruising all across his lower abdomen from where the harness had stopped his fall, just like a seat belt injury in a car crash.”

By 10:49, the three severely injured survivors had been evacuated and were en route first to Pheriche, then to Lukla, then, by low-altitude heli, to Kathmandu for treatment.

The Rescue mission now switched to body-recovery mode, a dangerous proposition since the glacier wasn’t any less likely to calve. Dave Hahn arrived from Base Camp at about 11. He and Andy Tyson had heard a report that there may have been a pair of legs sticking up through the snow.

“We got to the lowest extent of the debris, and we could see a glove on the snow and a backpack attached to someone,” said Tyson. While Hahn and his crew went off to investigate, Tyson climbed the triple ladder, now repaired, and found a lone boot, the leg inside it fractured badly, sticking out of the ice. It was Dorjee Khatri. His body heat had melted the snow around him, which then refroze.

Tyson, Garrett Madison, and Ben Jones chipped carefully around Dorjee Khatri’s body with the adzes of their ice axes, but by 2:30 P.M. they still hadn’t freed him, so they had to come back the next day. The weather was deteriorating, and New Zealander Russell Brice—founder of Himalayan Experience, who was coordinating heli flights from Base Camp—told them they should stop for the day if they wanted to fly down.

Below them, Hahn guided in the last body-recovery flight of the day, raising his arms in a Y signal to bring the long line down to him. Watching from Base Camp, Dr. Wallace reflected on the horror of the flights. “The lifeless bodies hanging from below the chopper, still with their helmets and crampons broke my heart,” she wrote. “We initially thought that confirming death in profoundly hypothermic patients might pose some problems, but the extent of some of their injuries made it depressingly easy.”

Once he’d done all he could, Lakpa Rita walked wearily down to Base Camp. “When I got to the lower helipad,” he said, “all the boys were lined out and they had badges”—pieces of duct tape, with names written on them, identifying the corpses.

To reach the Khumbu region of Nepal, climbers typically fly the 85 miles from Kathmandu to the mountainside airstrip at Lukla. Below Lukla, which sits at 9,000 feet on the Dudh Kosi River, are foothills and lowlands. Above it, the trail to Everest slants upward along the Dudh Kosi, past Namche Bazaar (12,000 feet), the monastery at Tengboche (12,700 feet), Pangboche (13,000 feet), and Pheriche (14,000 feet), before leaving the river and climbing onto the Khumbu Glacier just below the tiny seasonal outposts of Lobuche (16,000 feet) and Gorak Shep (16,900 feet). The Thame Valley follows the Bhote Kosi River northward from Namche Bazaar toward Tibet, passing the towns of Phurte, Thamo, Thame, Ylajung, and Taranga, before the landscape gets too high for permanent settlement.

At Base Camp on the afternoon of April 18, Lakpa Rita jumped into a heli with Laing and made the five-minute flight to Pheriche. There, he was horrified to discover that a Nepalese army officer had confiscated ten of the bodies that had been recovered and that most of them had already been flown in the military’s Super Puma helicopter to Lukla, where they were laid out on the tarmac in full view of tourists landing there to begin their trekking vacations.

“I was so upset,” said Lakpa Rita. “My people did not need to go to Lukla.” So he flew there and negotiated with an officer to let him take three of his four dead back up to their families in Thame. Lakpa Rita signed over the fourth, Nima, to his uncle and brother, who wanted to fly him to Kathmandu for his series of pujas. The other six Sherpas were flown to Kathmandu and given to their families.

Tenzing Chottar’s body was never found, causing serious distress to his family in Ylajung, since that meant his soul might be wandering lost. After Lakpa Rita signed for his three men—Ang Tshering, Mingma Nuru, and Dorji—he flew back to Namche Bazaar, the Sherpa commercial capital, to meet Todd Burleson, co-owner of Alpine Ascents.

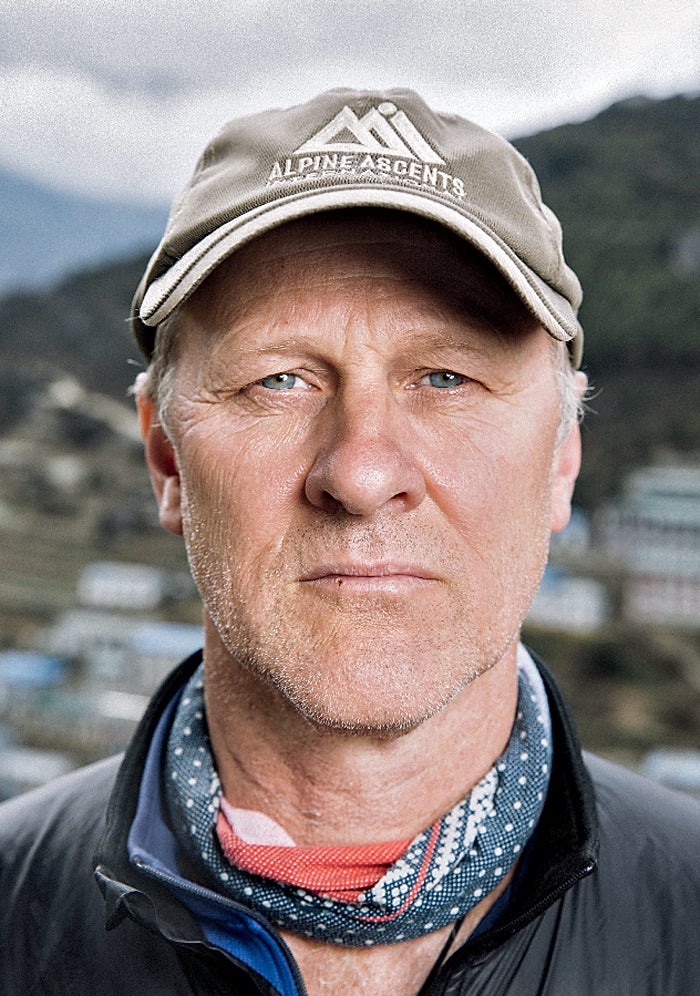

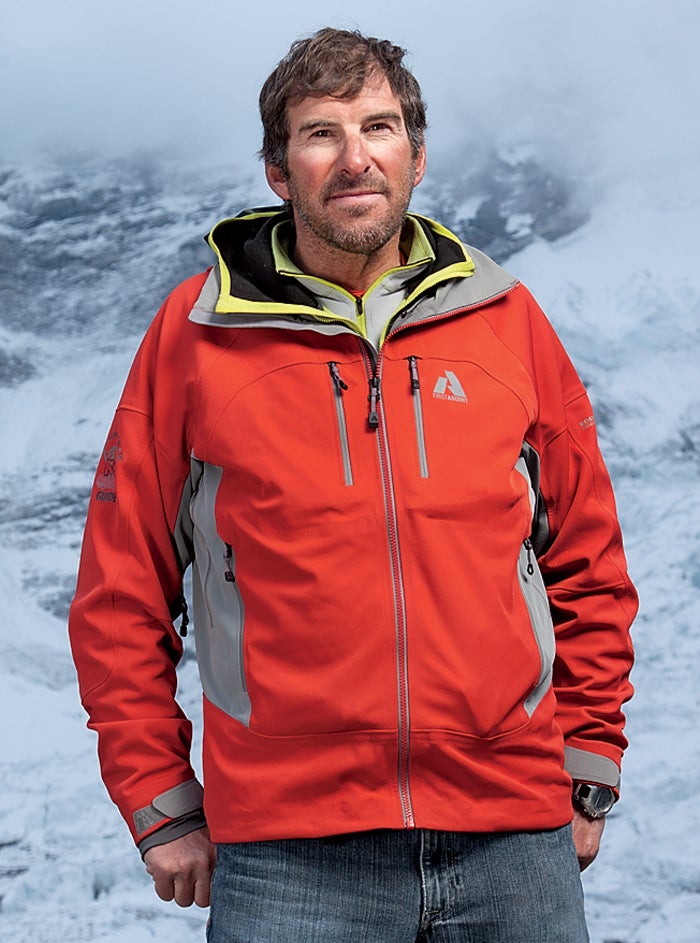

Burleson stood waiting on the helipad in Namche Bazaar. He’s big—six foot three—and graying now at 54. Like his employees, he constantly wears the logoed baseball cap of the guiding company he launched in 1986.

The hundred-foot-wide landing platform in Namche Bazaar, at 12,000 feet, is constructed without mortar, using granite hunks. When Lakpa Rita choppered into view, the pre-monsoon mists were already rolling across Thamserku and Kongde Ri, the 20,000-foot peaks above town, and a group of monks were on their way down the Bhote Kosi River trail from the monastery above Thame. The helicopter touched down, its rotors still spinning, and Lakpa Rita stepped out.

“I started to unload the dead bodies, and I got a hug from Todd,” said Lakpa Rita. “We were crying.”

“We hadn’t seen each other since all this,” said Burleson, who’d been in Kathmandu when the avalanche hit. Burleson’s regard for Lakpa Rita, a naturalized U.S. citizen who lives most of the year in Seattle, is boundless. He calls the years they’ve spent guiding together “the best partnership I’ve ever had.”

They laid out the bodies, and the heli took off. Ang Tshering, Mingma Nuru, and Dorji were bundled in their sleeping bags, which were wrapped in blue tarps laced shut with Korean rope.

“The police were asking us to take off their harnesses,” said Lakpa Rita. “I undid all the harnesses so the police could take pictures.” The officers inspected the bodies for wounds, to determine a cause of death that could be given to Kathmandu-based Shikhar Insurance as proof that each of the men had died in a climbing accident, qualifying his stated beneficiary for payment. During this two-hour process, the monks, in their red and saffron robes topped with polar-fleece jackets, began to arrive from Thame.

“Pemba Tenzing decided to take his father home that night,” said Lakpa Rita. “A bunch of monks came for Mingma Nuru and Ang Tshering. They had a stretcher, and they carried them to their houses.” Mingma Nuru lived a half-hour to the west, at a bend in the trail past Phurte. Ang Tshering lived in Thamo, 30 minutes farther on.

“There were a lot of people, maybe 18 or 19,” said Pemba Tenzing, “carrying turn by turn.”

That left the body of Dorji, who lived on the rocky flats of Taranga, half a day’s walk up the Bhote Kosi River from Namche Bazaar. “I didn’t know whether his wife had even heard the message or not,” said Lakpa Rita. “So we brought him to the police station here.”

Some locals carried the body to a set of barracks. Lakpa Rita went to the monastery, where Lakpa Doma, who with her husband, Sherap, runs an inn called the Panorama Lodge, helped him melt the fat and fill the brass cups and set and spark the wicks of 100 tea lights.

“There was a lot going on in my head,” said Lakpa Rita. “How to deal with the families, how to support them in the future.”

He and Burleson had dinner that night at the Panorama. They drank cans of Tuborg beer and sat in silence. “Then I took a shower,” said Lakpa Rita. “I really needed it.”

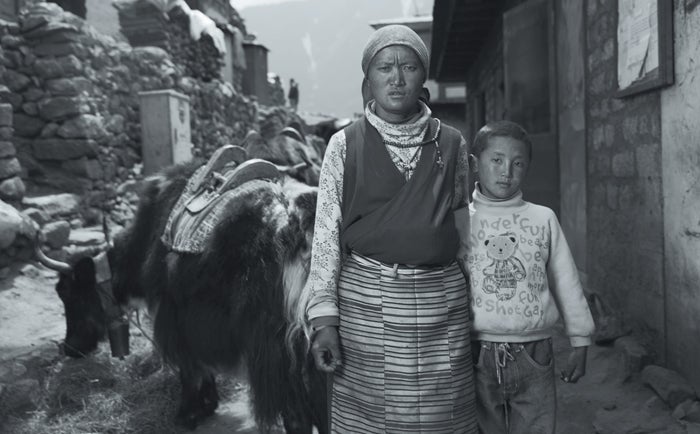

That same afternoon in Taranga, a barren huddle of 25 stone houses, Dorji’s wife, Ang Nimi, pack-saddled her yaks and drove them down to Thame to summon the monks and collect birch and juniper for the cremation of her husband. When she heard the news, she’d been brewing rice beer to give to the family of her uncle, Lakpa Dorje, who’d just died of gastritis.

“If I had received the message earlier, it would have been easier, since there were monks in my neighborhood who did the cremation of my neighbor” who had also died, Ang Nimi said. “The message came after all the monks were gone.”

Taranga sits at 13,200 feet on the road to Nangpa La, the 19,000-foot pass into Tibet that’s been used by traders and refugees since the 1500s. Two miles south, the Thame monastery is perched high on a cliffside above town, in the shadow of 21,000-foot Teng Kangpoche. But when Ang Nimi, who is 39, reached the monastery, it was empty.

“They were already taken to other villages,” she said. The disaster’s toll was large enough to cause a shortage of monks.

The fact that so many of the men who died were from this single drainage is not surprising. The Thame Valley is home to some of the most famous climbers in Everest history, including the late Tenzing Norgay—the first man to summit Everest, with Edmund Hillary in 1953. He lived with his grandmother in Thame before moving to Darjeeling, India, to find expedition work. Another notable local is Apa Sherpa, who is 55 now and lives in Salt Lake City. Apa is tied for the record number of Everest summits, with 21.

Thame’s finest climbers hold a geographic dominance not unlike the Kalenjin tribe of distance runners in Kenya, and it seems logical that it’s rooted in genetics. But Lhakpa Gyalgen, along with several other Sherpas from the area, offered a simpler explanation: “People are less educated here, that’s why.”

Since the commercialization of Everest climbing took off in the late 1990s, the Thame area’s economy has been dependent on Alpine Ascents and steered mainly by Lakpa Rita, who caught the climbing bug early. “I went to school in Khumjung and always wanted to be a climber,” he said. “Every year, Tenzing Norgay and Edmund Hillary used to visit us. We used to sing a song called ‘Our Tenzing Sherpa Has Climbed Everest.’ ”

Burleson met Lakpa Rita on the mountain’s north side in 1990, when the Sherpa was 24, carrying loads during an attempt of the direct route up the Japanese Couloir. That was the year American climber Jim Whittaker led the International Peace Climb that supported Ed Viesturs’s first Everest ascent. While Lakpa Rita didn’t stand on the top that spring, he made his first of 17 summits the following fall while working for a Yugoslavian team.

“As we were bringing Dorji in, his four little kids were crying, crying, crying,” Lakpa Rita said. “We said, 'We're sorry, but we are going to help you guys.'”

“He had an amazing pace and was able to manage people and do accounting,” Burleson told me, then recalled a story from the Yugoslavian expedition. “He carried a load to the South Col so quickly that, when he came back, they accused him of not making it.”

Two years later, and every year since, Burleson has hired Lakpa Rita to be his sirdar, a Hindi word for a local military leader, used during the height of British rule in India, between 1858 and 1947, when most of the early siege-style Himalayan expeditions were launched. Lakpa Rita marshals an army of local muscle to help Alpine Ascents’ clients reach the summit. Of the roughly 400 people who live in Thamo, Thame, and their outlying villages, most families have at least one person who has worked for Alpine Ascents, either directly or indirectly.

“This season I had almost 40 Sherpas working for me, most of them from Thame,” Lakpa Rita said. And that’s just on the mountain. Lakpa Rita also had to move 26,445 pounds of gear and food to support the Discovery Channel’s plans for a complicated live broadcast from the summit, which was quickly scuttled after the avalanche. He arrived in Kathmandu from Seattle on March 29. There he retrieved 98 cardboard boxes, each packed with 50 pounds of food that he and guide Eric Murphy had bought from Costco, Trader Joe’s, and Fred Meyer and then shipped to Nepal via Korean Airlines, at a cost of $120 per box, not including duty.

At the three-story Kathmandu warehouse of Alpine Ascents’ in-country trekking agent, Jiban Ghimire, Lakpa Rita and 30 of his 40 climbing Sherpas packed tents, gear, food, and oxygen into a large truck that was driven 16 hours to the end of the road in Jiri. It was met by a Russian heavy-lift helicopter capable of shuttling all that tonnage, in ten loads, to the Syangboche airstrip above Namche Bazaar.

“It’s not cheaper, but it gets there faster,” Lakpa Rita said. From the airstrip, porters and yaks can make what is usually a five-day walk to Base Camp in three days. “I don’t know the exact number,” said Lakpa Rita, “but we had at least 400 yak loads going to Base Camp and 300 porter loads.”

At Base Camp, each porter trades his load for a chit, a note with a signature that says what was carried—either a 66-pound single load or a 132-pound double load—and over how many one-day trail segments. A single load carried over the five segments between Namche Bazaar and Base Camp is worth a little more than $50 in wages.

On the mountain, the pay structure for Sherpas is similar. As is common at many companies, Alpine Ascents’ workers get a gear allowance of roughly $2,000 to $3,000 at the start of the season. Then they make $15 per day as a base rate and earn $20 per load to Camp II, $30 to Camp III, and $50 to the South Col, with a $500 to $800 bonus for summiting the mountain, a purse that roughly 200 Sherpas will claim each year. The best porters can make up to $6,000 per season, which is comparable to what a Kathmandu college graduate might make in a year. Sherpas who don’t make as many carries or who work for smaller local outfitters might make $2,000 to $3,000.

“Each sirdar hires people from his own town,” says Lakpa Rita. “One of the reasons is I know them better. The other is I want my neighbors to have the opportunity. I know climbing mountains is one of the best ways to make a living, especially in Nepal. I’m trying to keep the money in my neighborhood. Pretty much all, I hire from my hometown.”

For Dorji, Ang Nimi, and their four kids—two boys and two girls, ages six to twelve—Lakpa Rita and Alpine Ascents represented an escape. They lived in a single-story stone house no bigger than a garden shed. In the winter, when their neighbors moved to lower elevations with their yaks, they had nowhere to go. So they brought the animals inside the cramped space, with people and beasts eating the same potatoes grown in a few small patches of arable land. “There are maybe four other families that stay in the winter,” Ang Nimi explained to me.

The hope was that Dorji would work on Everest for a few more seasons and they would save enough money to build a winter house in Thame or Ylajung. But each year something would come up to delay the dream—including several family deaths prior to 2014.

“They all died in the past five years: his father, his mother, I think hers,” said Burleson. “All the money he made went toward pujas. He died broke, and they have no money.”

The next morning, as Ang Nimi was returning to Taranga from Thame, Burleson and Lakpa Rita followed a procession of Namche youth who carried Dorji’s body from the police station back to the helipad. There, around 8:30, they met Pemba Tenzing, who’d walked back to Namche Bazaar to help bring Dorji home. They flew west and then northwest, toward Cho Oyu, the world’s sixth-highest mountain, passing over Ang Nimi and her yaks before landing in a potato patch in Taranga. Lakpa Rita convinced the pilot to shut down the helicopter and give them 20 minutes to spend with the family, in hopes that Ang Nimi would arrive.

Burleson and the two Sherpas entered and set Dorji’s body down on the floor. “They had butter lamps lit, and they were doing their puja. The neighbors offered us tea,” said Lakpa Rita. “It was just too hard to drink tea. As we were bringing Dorji in, his four little kids were crying, crying, crying. And it broke our hearts. Todd and myself said, ‘We’re sorry, but we are going to help you guys.’ ” In all, the avalanche had left behind 28 fatherless, dependent children.

Burleson and Lakpa Rita told Ang Nimi’s neighbors that they would return to pay her Dorji’s salary and put the kids in school in Namche Bazaar. The pilot started up the helicopter. Then the three men climbed in and were gone.

For Burleson, the avalanche brought to mind an earlier episode, in 1995, when a Sherpa had failed to clip into a safety rope on Everest’s Lhotse Face and fell to his death. “Lakpa Rita and I carried the body down through the Icefall and then dragged it to Lobuche,” he said. “The mother and sister and brother, who was crippled, met us below Lobuche. She kept kissing my hand and thanking me for bringing him down. The brother wanted to drag the body himself.”

For the 1995 cremation, they chose a flat spot among a garden of chortens below the outpost of Lobuche. The memorial spot, on the Khumbu Glacier’s terminal moraine, now also includes engraved cairns for Scott Fischer, Alex Lowe, and other notable climbers who’ve since died in the Himalayas.

“When you’re burning bodies, it’s real,” said Burleson, wearily describing the gruesome practicalities of ritual body disposal in a cold, barren world. “It takes a lot of wood. You have to crush the skull and puncture the stomach, or else you just get a glowing bubble in the fire.”

In the Buddhist religion, the spirit undergoes bardo, a transitional period after death that lasts 49 days. During bardo, the soul gradually moves away from the body and toward reincarnation in one of the realms inhabited by gods, demigods, humans, animals, hungry ghosts, and devils.

The body lies in the home for three days before cremation. The entire village gathers at the deceased person’s house, where a kitchen tent is built and neighbors bring food and cash to help out. The family distributes gewa on behalf of the dead, handing out rice, butter, and money to anybody—even a reporter—who shows up. The gifts aren’t meant to please the receiver but to improve the rebirth prospects of the dead.

On April 29, at Mingma Nuru’s house in Phurte, I witnessed the gravity of the ceremony. Thirteen monks filled the house, meditating and praying during an event that was held under a new moon, to amplify goodwill. The belief is that the spirit lingers close to the body for three weeks. Any Sherpa climber lost in a crevasse is thought to have a restless ghost loitering nearby.

“The family has to talk near the body,” said Pemba Tenzing. “Before it we placed his favorite food, tsampa”—roasted flour mixed with broth to create a dumpling-like ball.

Mingma Nuru’s young wife, Dawa Jangmu, from Ylajung, sat in stunned silence on the floor of the kitchen, amid the commotion of monks and relatives. Widows describe this state in a way that’s always been translated to me as “paralysis.” She and Mingma Nuru hadn’t been formally married, and his mother was listed as the beneficiary on his insurance form.

“I don’t know what I’ll do,” Dawa Jangmu said quietly. She had also lost her brother Tenzing Chottar.

Lakpa Rita helicoptered back to Everest Base Camp in the early afternoon of Saturday, April 19. The last of the body-recovery efforts had just concluded. Three men hadn’t been found and likely won’t be for a long time. Like most victims of the Icefall, their bodies will gradually be moved, churned, and broken down by the currents of ice. Body parts and gear will rise up and melt out eventually, a femur emerging from the snow here, a glove there.

“I got a call from Jagged Globe’s sirdar, Pasang Tenzing, and he said we needed to make a report about the missing Sherpas,” Lakpa Rita said. “If you say ‘missing,’ sometimes it’s hard to get insurance.” They had to gather eyewitness reports saying that the men weren’t lost but entombed.

That afternoon, Lakpa Rita met the other sirdars at the camp of the Sagarmatha Pollution Control Committee. This was the first in a series of encounters that gradually spelled the end of the 2014 climbing season on Everest’s south side. It started with people giving statements to a government liaison officer about the lost men.

“Then the meeting turned to a different subject,” Lakpa Rita said. “A lot of other Sherpas and sirdars were bringing their own points, saying, We need to do this. We have to do that.” Specifically, the mood in the room was that everybody needed to go home.

“They decided to have a meeting the next morning at nine with the expedition operators,” Lakpa Rita said. “They asked me to present, but I said I can’t, because a lot of them were saying we should go home. I told them it was a big loss for me but I couldn’t tell people to go home. Everybody should make their own decision. I’m pretty sure I’d already made my decision, but I didn’t tell my climbers”—meaning the Discovery crew and 12 Alpine Ascents clients. “But I told my Sherpas, ‘This is it. We’re not going back up.’ ”

What followed was a historic rift in Base Camp that was soon being debated around the world. On every media platform, people weighed in about the fraught business of hiring porters to help Westerners reach the summit, with a clear majority deciding that it was fundamentally wrong for Sherpas to shoulder so much of the risk on behalf of guided clients who would never make it without massive human support.

“Sad day with Sherpas’ deaths in #EverestAvalanche; died prepping the route for rich Western climbers,” read a typical tweet in the days following the disaster. In a syndicated op-ed cowritten by one of Tenzing Norgay’s sons, Dhamey Tenzing Norgay, the avalanche was compared to last year’s Rana Plaza garment-factory collapse in Bangladesh, which killed more than 1,100 workers. “The loss underscores a growing divide,” the piece said, “between expedition members, who pay top dollar to reach the summit, and their highly skilled Sherpa guides, who are paid a relative pittance and too often are taken for granted.”

Others pointed out that everybody who sets foot on Everest is taking a gamble—and that, if the avalanche had happened later in the season, all the victims might have been guided clients. “They know the risks,” wrote climber Mark Jenkins on National Geographic’s website, noting that “Sherpas are not dragooned onto Everest.” IMG guide Mike Hamill, writing in The Wall Street Journal, sought to explain Everest’s labor problems as a private matter by blaming them on “media sensationalism… perpetrated by persons outside the Everest mountaineering community.”

Hamill’s take, that the climbers and Sherpas share a mutual destiny defined by the “brotherhood of the rope,” is what many Western guides feel in their hearts, but it falls short of reality when you consider how much more time Sherpas spend roped to their actual brothers than to Westerners and how many more trips they make through the Icefall.

Looking back on it now, the events of the week following the avalanche are probably best described as a complicated mix of posturing and political theater that reflected how much was at stake, for the Western climbers who’d paid their outfitters $18,000 to $90,000 (nonrefundable) to attempt the climb, for their guides, and for the Sherpas whose lives and livelihoods were in jeopardy.

Among the first to find themselves struggling with the explosive politics of Base Camp were the Discovery Channel and 39-year-old Joby Ogwyn, the Louisiana-bred adventurer who had done a months-long national media blitz leading up to what was supposed to be a live, televised wingsuit jump expected to attract tens of millions of viewers.

The Discovery Channel had invested heavily in the stunt, and because the prime-time broadcast was going to be live and would use multiple cameras, it required an enormous amount of satellite equipment and manpower. Broadcast crews were to be positioned at the summit of 27,940-foot Lhotse, at Everest’s Camp II, and also on the summit itself, at 29,035 feet. For these tasks, Discovery had hired AAI guides Ben Jones and Andy Tyson to assist the high-altitude cameramen, which included Scottish climbers Ed Wardle and Joe French and Jackson Hole’s John Griber.

But by the evening of Friday, April 18—the day of the avalanche—members of the Discovery crew began to send conflicting messages about what would or should be done next. “For something like this to happen makes the whole thing seem pointless to me,” Wardle told the UK’s Channel 4 News that night. “The agreement here among everybody at Base Camp is that the mountain is closed for now. Nobody will be climbing.”

That same night in Base Camp, Madison Mountaineering’s Jangbu spoke with Ogwyn, who told him the wingsuit stunt wasn’t important compared with the loss of life. “Whatever you guys decide,” Jangbu recalled Ogwyn telling him, “I will support that decision.”

The next morning, though, Ogwyn seemed to reverse field, posting a note on Facebook saying, in part, that he was not giving up. “Today is a brighter day,” he wrote. “We are staying on the mountain to honor our friends and complete our project.”

Behind the scenes, his cameramen were furious, as I learned after I arrived in Kathmandu on April 22. “He’s going to fly off the summit to honor his dead Sherpas? That’s pathetic,” Griber told me when I ran into him at a rooftop restaurant. “How many people have to die on Everest for you not to jump?” Wardle insisted that Ogwyn cancel his project, a call that Ogwyn claimed wasn’t his to make. “That’s a decision that’s going to get made in New York,” he told me when I talked to him in June.

On the 19th, a threat arrived via Base Camp’s oldest, most resilient communication system: the rumor mill. “It was basically that if Joby didn’t leave, something like what happened last year might happen again,” said Ogwyn’s guide, Garrett Madison. He was referring to a fight that took place at Camp II in 2013 between several Sherpas and three professional European climbers, who’d angered the Sherpas by climbing above them while they were fixing line on the Lhotse Face.

“It wasn’t like I was being run out of Base Camp, though I took it seriously,” Ogwyn said of the threat. He and Madison left Base Camp that day and walked to Gorak Shep. In a sign of the rising discord, a crew member from NBC changed the name of their local wireless network to “He ran away!”

The broadcast’s executive producer, Howard Swartz, had just arrived at Kathmandu’s Hotel Yak and Yeti, and on April 20, Ogwyn flew from Gorak Shep to Kathmandu to meet him. The decision that emerged from their talk was clear: no go. That day, Discovery released a two-sentence statement saying that, in light of the tragedy and out of respect for the dead, the jump was off.

“His heart was in the right place,” Swartz told me on April 23, of Ogwyn’s short-lived attempt to keep the project alive. “But, really, it was an easy decision.” Then his tone softened, and it was clear how shocked he was by what had happened to the Sherpas. “I had a binder of contingencies this thick,” he said, opening his hand wide enough to grip a pint glass. “This wasn’t in it.”

Discovery Channel, which had already secured airtime for its special, shifted gears. NBC crew members still in Base Camp shot a 90-minute documentary about the avalanche, which aired on May 4. Ogwyn set up a fund for the families of the 16 dead that eventually raised about $100,000. He left Nepal on April 24 and went on a media tour, giving a series of interviews—alternately informative, heartfelt, and tone deaf—that made it obvious he intends to go back. In New York, at the end of April, he told a blogger that Sherpas “are far from slaves” and that he would return to Nepal in the spring of 2015 to make his jump. “I have done a lot more producing and setting up lecture[s], and a lot is based on this,” he said. “Next spring will be my opportunity.”

When I spoke with Ogwyn, he confirmed that he’s going back next year, and he probably won’t have any trouble finding an outfitter to support his effort. Meanwhile, he was still angry with Wardle: “Ed Wardle, my cameraman, just couldn’t keep his damn mouth shut, which is incredible, because he’s a cameraman and has no business being on TV, much less challenging me in my expertise.”

“The show’s about me,” he continued. “The show was about a guy named Joby Ogwyn jumping off the tallest mountain in the world. Simple as that.”

The purpose of the gathering at Base Camp on Sunday, April 20, was never in doubt. It was an organizing meeting for a labor force, many of whom felt aggrieved. The 21-person group assembled inside the tent of the Sagarmatha Pollution Control Committee were mostly Sherpas, along with two low-level government liaison officers. A few Westerners were also present, including Dave Hahn, Canadian Tim Rippel of Peak Freaks, Russell Brice, and Greg Vernovage of IMG. A Nepali outfitter named Dawa Steven, who co-owns Asian Trekking, helped translate for the Westerners.

“The Sherpas were angry but peaceful,” said Lakpa Rita. The government had offered to pay the families of the dead an additional $400 on top of their $10,000 insurance payments, which was taken as an insult. “The money wouldn’t meet the cremation expenses,” said Pasang Bhote, a Sherpa from the Sankhuwasabha district, near Makalu, who was working for a small local outfitter called Seven Brothers.

Not everybody found the meeting so cordial. In an account written after the season ended, Brice recalled that “a brawl almost broke out between the liaison officers and some of the fired-up Sherpas, and it took the efforts of the Western members present to calm things down.”

The obvious leader for the workers would have been Dorjee Khatri, Garrett Madison’s late sirdar. He was vice president of the Union of Trekking Travels Rafting Workers Nepal and a member of the middle-left United Marxist-Leninist Party, which in 2005 had formed a coalition with the center-left Nepali Congress party and several hard-left Maoist parties to form the CPN-UML and replace Nepal’s monarchy with its current Constituent Assembly. Dorjee Khatri’s death politicized the tragedy almost by default. The following day, union leaders and Nepal’s CPN-UML prime minister from 2009 to 2011, Madhav Kumar Nepal, attended Dorjee Khatri’s funeral in Kathmandu. Party and union members draped his body in the flags of their respective organizations.

With Dorjee Khatri dead and the government paying attention, the Sherpas decided to air some grievances—about the dangers they face and about the modest money they make relative to the $3.4 million the government of Nepal collects from the climbing companies each year. Pasang Bhote, who had worked with Dorjee Khatri at Adventure Consultants for three Everest seasons, became the most prominent voice of the Sherpas, though he bristles at being called the leader of a movement or a Maoist, as several local news outlets dubbed him in the weeks after the avalanche.

“We were not affiliated to any parties,” he said. “Our sole understanding was we were laborers and the government had insulted us, and it was wrong.” Pasang Bhote came to the meeting with a list of demands for the government. After he read them off, others began adding to the list, and a liaison officer dutifully scribed the results into what became known as the 13-point charter.

Sumit Joshi, who co-owns Himalayan Ascent and has lived in Australia for the past 15 years, explained the demands to the Western guides present. The charter called, in part, for a second doubling of accidental-death insurance payouts—coverage was increased in the spring of 2013—to about $22,000. The Sherpas wanted $10,000 in disability coverage for workers permanently injured in the mountains, a $1,000 funeral stipend, a permanent relief-and-education fund carved from 30 percent of the government’s permit royalties, a plot of land in Kathmandu to build a memorial to the 16 dead, and official recognition of the cursed season as a lo nak (“black year”), by making April 18 a national holiday. Most important to the Westerners present, the charter stated that no team should be prevented from climbing.

“One of the points was that each expedition would decide on its own whether to continue, and that nobody would be pressured by those not continuing,” Dave Hahn told me. “That was one of the things we were agreeing to. And I think by the following day I heard that list read out to a chanting crowd, and it had been changed to: ‘And none of us will climb this season.’ ”

Almost everybody inside the tent signed the original 13-point charter. Outside, a crowd of Western guides and Sherpas had gathered. Pasang Bhote stood and read out the list. He and Sumit Joshi became the town criers, with Pasang orating and Sumit translating. “There was no microphone,” Pasang said. “I had to shout.”

“Obviously, because it’s political and everything, Pasang Bhote also said to people, ‘Do you want to continue or not continue?’ ” Sumit Joshi later explained. “And everybody yelled, ‘Yeah, we don’t want to continue!’ ”

Sherpas from outside began filing into the tent to add their names to the document. An additional 274 signed the paper, which threatened protests if the demands weren’t met. Pasang Tenzing, the secretary of the Nepal National Mountain Guide Association, delivered a copy of the charter to the Ministry of Culture, Tourism, and Civil Aviation in Kathmandu.

The document stipulated that any expeditions whose Sherpas wanted to continue could continue, but that’s not how things played out. “After the avalanche, people were really scared,” Sumit Joshi said. “Underneath, I don’t think there was one single Nepali in Base Camp who wanted to go up again. Whatever these Western leaders are saying, that’s all false, I think.”

Initially, his assessment was probably right. “Their relatives were telling them, Don’t go up there,” Hahn said. “Two days afterward, my guys didn’t feel like climbing—quite understandably—but that changed a few days later, to the point where my Sherpas wanted to climb again.”

This matched a pattern that several other Western outfitters described to me. But the movement to keep going was outweighed by stronger pressures to go home.

On April 22, with the body-recovery effort officially called off, everybody in Base Camp gathered for a memorial puja. Between 400 and 500 people were on hand. Many Sherpas had returned to their villages, but many were still there. By all accounts, the service went smoothly. Juniper was burned, tears fell, black tea was offered, and prayers were made.

Afterward, the crowd lingered. “People were angry more because there hadn’t been any response from the government,” said Sumit Joshi. Fist-pumping and chants calling for the season to end started up. Then came the source of the Base Camp talk about threats: somebody in the crowd shouted, “If anybody goes up, we might break their leg with an ice ax!”

IMG’s head guide, Greg Vernovage, was there with his company’s longtime sirdar, Ang Jangbu. “Jangbu and I were together near the end of the puja,” he said, “and someone said that if there’s climbing, they would go down to Kathmandu and burn the offices and homes of the local operators.”

By Wednesday, April 23, things had gotten worse. Base Camp was awash in gossip that Nepalese troops would soon arrive to restore order. After some backroom haggling that involved Brice and Altitude Junkies' Phil Crampton, the government finally announced that it would send tourism minister Bhim Prasad Acharya by helicopter to Base Camp to try and ease tensions.

That evening, a group of local and Western guides, most of them certified by the International Federation of Mountain Guides Associations (IFMGA), met at the Sagarmatha Pollution Control Committee camp to discuss conditions on the mountain and how they might keep the season alive.

“As we went round the circle expressing our safety concerns,” Alpenglow Expeditions owner Adrian Ballinger told me in a text message sent shortly after the meeting, “much less was about Icefall dangers and much more was about Sherpas.”

The meeting broke up, and that night several expeditions announced that they were pulling the plug. Canadian Tim Rippel, owner of Peak Freaks, canceled his climb, writing on his blog: “There is talk of retaliation on Sherpas who want to continue, and I’m not about to be part of this or put any of my staff or clients in danger.”

After interviewing numerous outfitters, sirdars, and other Sherpas, I was unable to find any specific threats beyond those shouted at the April 22 puja. But the environment was still hostile. “No one came to me directly to challenge me or threaten me to my face,” Asian Trekking’s Dawa Steven wrote in an e-mail. “I only heard through second-hand sources.”

IMG client Ellen Gallant, a cardiologist from Salt Lake City who trained and saved for 12 years and recently quit her job to climb the mountain, said she saw the effect that the chanting had on her sirdar. “Jangbu was clearly upset and crying about this,” said Gallant, who like most Western clients found herself out roughly $50,000 that her insurer, Travelex, was unwilling to cover. “Ang Jangbu, if you know him, is a stoic man. Nothing upsets him.”

As for herself, she’s still coming to grips with the collapse of a goal she’d worked toward for years. “I know it’s a small thing in the midst of the rest of the tragedy, but I feel like there’s a hole in my heart,” said Gallant, who turned 48 on May 12. “For a decade, I imagined standing on the summit of that mountain on my birthday.”

Without exception, each of the Western outfitters that wanted to stay and climb believed that they had a special relationship with their Sherpas. “We have a full complement of loyal Sherpas who we have worked with for years,” British outfitter Tim Mosedale wrote on his blog. “They have all returned after the tragedy and even the ones who have lost brothers who were working for other teams are willing to continue.”

But some Sherpas obviously were frightened. In recent years, a new crop of local, Kathmandu-based outfitters has grown up with a goal of owning the entire Everest production rather than just the load-carrying part. The rift in 2014, which is the same one that arose during last year’s Camp II fight, is between younger Sherpas who are training to be independent mountain guides and older Sherpas who have done well by making a career working for the top Western outfitters.

Sherpas from the local outfitters who were at the center of this year’s uproar—ones who were willing to speak at all, that is—claimed to have no idea that any of this was happening. When I asked Tashi Sherpa, the director of Seven Summits, whether there was some sort of Sherpa-enforced climbing moratorium, he said, “I don’t know about that, man. That is a personal decision if you want to climb up. But the route is not fixed.”

Ultimately, what was going on was both mind-numbingly complicated and also pretty simple. There was no blanket Sherpa or Western position, but rather a messy soup of grief, labor politics, service-industry customer relations, and government posturing that caught many experienced guides by surprise. While mountain climbers tend to be both liberal and freedom loving by nature, the realities of collective bargaining, especially done informally and without clear leadership, must have come as a shock.

An American woman named Cleo Weidlich vowed to complete her solo climb of Lhotse, proclaiming on Facebook, “I refuse to give in to the pressures of the Everest mafia.”

Another factor was a famous Sherpa tendency to avoid conflict—even if conflict is what they desired. “Most of them are scared of dying but also of losing their jobs,” explained Nyima, a climber who owns Cafe de 8848 in Namche Bazaar. “You’re brought up in a culture where you treat Westerners with great hospitality.” Some of those men were willing to simply say that they didn’t want to climb or that their families were terrified for their safety. But more of them probably needed a way to save face about not wanting to go up. Blaming the threats of others, real or exaggerated, provided that.

“Some of the sirdars used it as an excuse. There was no renegade Sherpa group going camp to camp threatening people,” said Sumit Joshi. “If anyone can prove that, you know, that person should be in jail.”

Even as the 2014 season headed toward final collapse, there were undoubtedly plenty of Sherpas willing to climb. But there’s no such thing as a partial labor strike. “It’s absolutely real, the social pressure that’s going on not to cross the line,” said David Morton, a cameraman and former Alpine Ascents guide who was in Base Camp working on the forthcoming feature film Everest. It’s just that some Western outfitters didn’t recognize what they were dealing with. That’s because their workers told them it wasn’t a strike, a semantic feint in a country famous for relentless deference.

So rather than appeal to their employers for better compensation and benefits, the Sherpas stopped working and aimed their protest at the government—a dysfunctional body that has seen six different prime ministers since its democratic reform in 2008.

And perhaps owing to those close relationships with their own employees, many outfitters believed what they were being told. “The Sherpas state that the situation is between them and the government,” Mosedale wrote on his blog. “The government are stating that the mountain is open for business. We are going round and round in circles.”

The loop finally closed on Thursday, April 24, when I hitched a ride to Base Camp to witness the day’s events. I ran into Madhu Sudan Burlakoti, joint secretary of Nepal’s Ministry of Culture, Tourism, and Civil Aviation. As he waited to board his helicopter, he assured me that the Sherpas were “ready to climb.… They are going to climb.”

My main takeaway from this was that nobody wanted to be seen as responsible for shutting down the mountain. For the government, doing so might have led to calls to refund the permit fees it had collected. The Sherpas, meanwhile, worked in one of the highest-paying industries in Nepal, though the cost of living in the Khumbu region has also risen sharply as a result of tourism’s success there.

When Minister Bhim Prasad Acharya and his entourage arrived in Base Camp around 10 a.m., a crowd had already gathered and was in a heckling mood. He addressed them while taking in oxygen through a nose tube and looking frail. “Please sit, please sit,” a handler said.

“Put some more chile in his soup!” somebody shouted.

“Turn off his oxygen and see if he notices!” somebody else yelled, to much laughter.

The minister spoke for an hour, saying that the government had agreed to let the expeditions roll their $10,000 permits into another year, a step that would make the shutdown a little less costly for clients. He told them he would put their 13-point charter in front of the cabinet. It was hardly a capitulation, but he’d shown up, and that was something.

After Acharya left, the expeditions began packing up. In an ironic turn, the lone group of Sherpas actually employed by the government, the Icefall Doctors, were the only ones required to stay, though they stopped maintaining the route. Climbing ceased almost entirely, but not quite. An American woman named Cleo Weidlich vowed to complete her solo climb of Lhotse, which shares the route up to Camp III with Everest.

“I refuse to give in to the pressures of the Everest mafia,” she proclaimed on her Facebook page at the end of April. During the second week of May, she and Wang Jing, owner and director of a large Chinese outdoor-gear retail chain, choppered to Camp II to begin their climbs. Jing made it to the top of Everest in late May, but Weidlich abandoned her Lhotse attempt, deciding that you can’t truly say you’ve climbed a mountain if you’ve flown halfway up it.

After the helicopter assists to Camp II, the government launched an investigation into the lawfulness of the flights. As the politics of Base Camp played out in April, several outfitters, especially HimEx’s Russell Brice, made their case that helicopters should be used to ferry gear over the Khumbu Icefall. It’s a move that could lead to fewer Sherpa deaths. But such a policy might also result in less work for them, more helicopter crashes, and widespread condemnation from climbing purists who think the mountain has already been brought low for the sake of commercial clients.

In the aftermath of the avalanche, half a dozen organizations raised nearly a million dollars to benefit the families of the 16 Sherpas who died. In addition to Ogwyn’s $100,000, a group of photographers from National Geographic and Outside raised $450,000, and there were major efforts by the American Alpine Club, the Juniper Fund, the American Himalayan Foundation, and a Japanese climbing team.

Most of the charities have pledged that all of the funds will directly benefit the families of the men who died. I was involved with the photographers’ effort, and half of that will go to families who lost climbers—either this year or in years past. The rest will pay for programs at the Khumbu Climbing Center, which trains Sherpas in safety and mountain rescue.

In the wake of past accidents, like those in 1996 and in 2012—when six clients and guides died over a two-day period—climbing Everest has only got more popular, since risk is part of the allure. But the impact of 2014 may be different, in part because of the political fault lines revealed so starkly in Base Camp. People who are saving up for the experience of a lifetime may have second thoughts about forking over upwards of $100,000, after airfare and gear purchases, when there’s no guarantee they’ll even set foot on the mountain.

So far, very few climbers have gotten any money back. The outfitters had already spent most of it moving equipment onto the mountain and paying guides and workers. And while it’s true that climbers may have a second chance to use their permits in the next five years, they’ll also have to pay the other Everest bills again.

And make no mistake: some climbers are angry. “We have been screwed by the Sherpas,” said Damien Francois, a 49-year-old Belgian who paid $28,000 to climb with an outfitter called Ever Quest Expeditions. “We are the hand that feeds the whole business, so without us, no operators. Without operators, no jobs for the Sherpas or their workers. But then we’re told, ‘Go home and come back next year.’ ” Francois, who says he’s writing a book about the 2014 “mess,” said he tried to speak out about all this at Base Camp but was told to shut up.

Among outfitters, the talk has already begun to shift from how to care for the families of the fallen to how to prevent more Sherpa deaths in the future. Besides using helicopters to shuttle gear to Camp II, it has been suggested that Camp II become a lot less luxurious, so there’s less stuff to haul back and forth. Many of the dead men in this year’s tragedy were carrying tents whose poles were big enough to be fashioned into makeshift stretchers. Adding helicopters to haul gear could change the equation, but whether that happens is still being debated.

Another way to reduce the number of Sherpas on the route is to restrict the number of permitted climbers. American alpinist Conrad Anker has suggested raising the bar by making a successful climb of another big peak in Nepal—like Makalu or Baruntse—a prerequisite for attempting Everest. That move might actually make money for the government, but it would put Everest even further out of reach for all but the wealthiest clients.

Meanwhile, the quality of maintenance in the Icefall route has come into question. Several guides I spoke with, including Hahn and Burleson, want to see some accounting for the $500 per person—or roughly $175,000—that outfitters annually pay the Sagarmatha Pollution Control Committee to fix the route. Hahn believes the level of route fixing and maintenance has not kept pace with increased traffic on the mountain. And the committee readily acknowledges that it uses a lot of that money for maintenance elsewhere in the national park that contains Everest.

As for the 13-point charter, the government has announced that it will require $15,000 in life-insurance coverage for climbing Sherpas (up from the current $11,000), but outfitters could elevate that to $20,000 at a cost of only about $200 per worker. Beyond that, it’s unlikely the government will forgo any of its royalties for the sake of a Sherpa relief fund. In the end, Everest’s economic ecosystem is as fragile as its natural one. Unless people are suddenly willing to pay half a million dollars to climb it, the steady pull of gravity will be toward the status quo.

Last January, before any of this had happened, Lakpa Rita tried to quit climbing. The spring of 2013 was also a bad year on Everest, mostly because of the fight that took place at Camp II. “After that incident, I told a lot of people I wasn’t going to climb anymore,” he said. The mood had changed. He didn’t understand what was driving some of the younger Sherpas anymore. In the initial aftermath of that fight, many people rushed to the defense of the Sherpas, who’d been shamed when the Europeans climbed past them on their home turf. But in the year since then, many people have begun to suspect that there is something more going on.

The great sirdars of the nineties and early aughts—men like Lakpa Rita, IMG’s Ang Jangbu, Adventure Consultants’ Ang Dorjee, Rainier Mountaineering’s Lam Babu, and HimEx’s Phurba Tashi—have lost some of the authority they once had to dictate decisions in Base Camp. Many young Sherpas are not mere porters anymore. A dozen have earned their IFMGA certifications (a long, expensive process that gives a guide the ability to work anywhere in the world and command a higher wage) and work for local outfitters based in Kathmandu’s touristy Thamel neighborhood. They have their own cliques and hierarchies.

It’s a rift that’s likely to deepen. Local outfitters and ascendant young Sherpas will continue to assert themselves as the government pretends that it has everything under control. And established Western outfitters, who still bring the best logistics, most qualified clients, and most experienced guides into the country each year, will struggle to compete with those local outfitters, who want a bigger piece of the pie but are also consistently the worst at taking care of their workers and their families after an accident. Many local companies charge their clients less than $30,000 for an Everest trip.

For Lakpa Rita, these shifts finally prompted an attempt, earlier this year, to find another way to make a living. The man whose image covers an area the size of a handball court on the side of the Sherpa Adventure Gear headquarters building in Kathmandu, began looking for work in Seattle.

“I drove an Uber,” he said. “I also tried landscaping.” He applied for a job as a mail carrier. “They hired me, but the next day I said I’m not going to do it.”

And so he didn’t. Instead, he returned to Everest in 2014. “I mean, this is what I know. This is what I’m good at. And this is what I enjoy doing,” he said. Plus, his neighbors in Thame count on him for work.

On that black Friday morning in the Icefall, as Lakpa Rita raced to the aid of the boys he’d watched grow up, his cell phone rang. He stopped and answered it. News of the avalanche had already reached Seattle, and his wife, Fur Dikee Sherpa, was on the line in tears.

She said, “No more Everest. No more K2. We can survive without climbing. You don’t need to climb. I don’t want to lose you.”

“I told her yes, I won’t climb anymore,” Lakpa Rita said. But then he hedged, as Everest climbers always do. “I will come back just to manage the Base Camp.”