Part of the Project

First Published in

Milton Glaser: We have to distinguish between a professional practice where a client and audience are concerned, and a personal practice where you are interested in the development of ideas that violate professional assumptions. Unfortunately they get lumped together in education but I think you have to be very careful when you are serving a public and a client. Students today frequently don’t understand that the profession is not about doing so-called experimental work. Schools are not clear about separating those activities.

Massimo Vignelli: Design is a profession and has a different set of responsibilities compared to those who consider graphic design an art form. While the artist can and should perhaps transgress, the professional cannot transgress, as they have to deal with client needs.

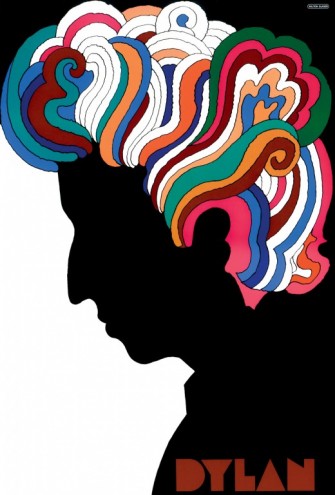

Milton: Every once in a while though, somebody who thought they were doing design, does enter into the realm of art. That happens because there are some things produced that go beyond the specific problem and somehow do something else, which in my view is to create attentiveness. Certain practitioners have managed to occasionally produce art. I have a very specific definition, which has served me over the past couple of years. I believe that art at its best is a meditation. If you look at something and it changes your idea of what is real, it is art. A glass or a piece of furniture can produce this effect. It is very hard to do intentionally. Then, every once in a while, something enters the world that goes beyond its functional requirement and gets into what you might call an experience.

Massimo: People ask me that very often: What is the difference between art and design? I say design is utilitarian; art is useful and non-utilitarian. Design is utilitarian, but sometimes it is not even useful. So in design, the more you go towards art, the less it is designing. In art, the more you work to do a design, the less art it is.

Milton: Some things function in both ways. It can be a work of design that does what it is supposed to do, while also elevating your understanding of reality. That is what happens at the very best level, but it occurs infrequently.

Massimo: And when an artist reaches that level, automatically it is timeless. It becomes good forever.

Milton: If it performs another function, the question is: What is that function? Beauty and aesthetics is part of what we do and, in my construction, beauty is merely a device to lead someone to attentiveness. You are led to awareness through beauty, because beauty is so attractive. We are programmed as a species to move towards beauty. The idea of aesthetics is in our brain, in our cells, and we are moved by the idea of beauty. What does it mean about the shape of a glass that makes one beautiful and another ugly? We have to examine this judgement that we all make. The issue of beauty in some way affects all professional practitioners.

Massimo: I don’t have that intent first and foremost. I am fascinated by the problem. Maybe it is because of my semiotic approach to life, where I like understanding what that product should be: What is the destination of it? What is the market for it? Will that alter? Who is the client? What kind of position must that type of product have compared to its competition? I am fascinated by all these elements and, by finding all these things, the answer comes about without thinking. The second element is the syntactical element when I start to work on the product and try to be consistent about every detail, matching everything – this means this and that means that, or this is right and that is wrong – according to the goal that you set for yourself. Thirdly, the pragmatic aspect of being confirmed by the client. When they understand what you have done, that expresses what you wanted to do. So I’m not motivated by something being noticeable, because I think that being noticeable is more of an artist type of endeavour.

Milton: Nobody good in this field or at the highest level has done it for either notoriety or money. They all loved their work. They were passionate and curious about it. Nevertheless we’re in business and one of the problems is getting significant work. You want people to come to you with a big project, not just a little paperback book. This is the reason why fame or notoriety is important. If you don’t become known, you will only get modest assignments. In order to have a career, you have to be conscious of the effect of your work on the world. If the work is not extraordinary, you are not going to get anywhere.

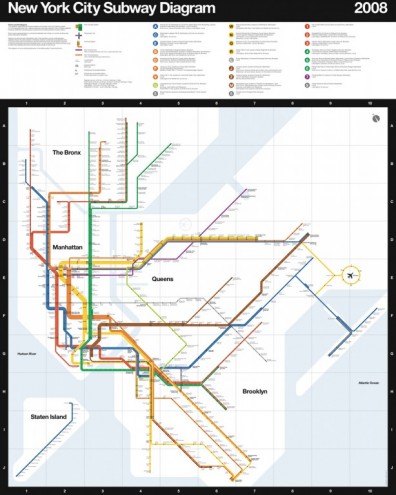

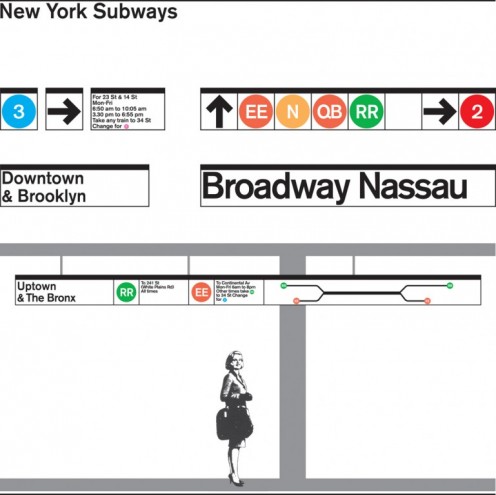

Massimo: To me, the work was always the by-product of an approach and a concept. Looking back at my life, when I started, I was anxious to do certain kinds of graphic structures and typography based on understanding the product – the semantics, syntax etc. Once I became good at doing small jobs, I wanted to get big jobs, which is why we started Unimark. We realised that large corporations didn’t like to talk to studios, they like to talk to other corporations. So we started Unimark with offices all around the world – a huge structure – so that corporations would feel comfortable and we could finally get jobs that we wanted to do. This is exactly what we got and the theory really worked out. The aim was to perfect the environment and substitute the trash with things that we thought were less trashy, which was our kind of design.

Milton: But that was not your client’s aim. Your client’s aim was not exactly your aim, although they were often congruent. Your client’s aim was to make more money, by presenting a style that was acceptable to a public who would feel secure by seeing things within a corporate vernacular.

Massimo: A good building costs no more or less than a bad building, and a good design costs no more than a bad design. Our aim was to transform these guys, giving them a different motivation for doing things besides the obvious one. There are tangible and intangible aspects. The profession takes care of the tangible aspect and the good professional can inject intangible values. Even a bad designer can cover the tangible aspects in a fairly good way unless he is very bad.

Milton: My problem is with the definition of good and bad. At this point, helping a bank sell more phony products to the public is not a good objective, so my instinct would be not to do anything for the bank.

Massimo: You can refuse the client. Or you can do it in a way that is less offensive, more consistent, more economical and more elegant, raising the standard of the cultural level to a higher level of appreciation.

Milton: If you could convince the bank that by virtue of more elegant typography, they would be more honest in their dealings with the public, that would be something. I sense that you believe that by elevating all this stuff to another level of understanding that even the bank’s president would feel more inclined to be more honest in his dealings?

Massimo: Not necessarily honest, but might acquire a better sense of quality. Therefore when he chooses an architect, he will choose a better architect than before and a new sense of quality that he didn’t have before will start to permeate his life. But if he is an unethical person, chances are that he will never understand anything good. You can’t give good design to Al Capone – he would never get it.

Milton: I would not easily admit this, but we have done some consulting for a big drug company that is doing extraordinary architecture with only the best architects in the world. But at the same time, they were just brought up on charges for milking the public and sued for a billion dollars for some kind of scam. How do you fit those two things in your mind? Is consulting on the aesthetics of the building unrelated to the activity of the corporation?

Massimo: Moral issues in our profession are very important. When I was a student in architecture, one of the typical conversations was: Will you ever design a church? You’d say: Yeah. Would you design a theatre? Oh yeah! A hospital? Yes, yes. Would you design a whorehouse? And there was the no. But then you grow up and begin to think that if the whorehouse exists, why should it be so gross and kitsch? Can’t we design a whorehouse that is elegant, which the world is full of now, as it turns out. It is similar to the issue that you just mentioned. Should we work for a client that does that? I think that what they do in the pharmacy business is their business and really doesn’t relate to their image in a sense. A building is a building – why have a bad building when you can have a good building? The communication, package, signage, exhibitions and all those things, can be good. By doing all these things well, they cast an image of themselves as a terrific company. If they are a terrific company and the answer is rotten, then our thinking collapses. But that might just be a detail on a specific aspect of their product, while the cultural benefit is positive. Do I like a company that does these things or do I prefer a company that makes a terrific ethical product, but has a lousy image? I think I may go with the first!

Milton: Given the choice of a terrific product badly sold or a fake product beautifully sold, I would have to go with the good product. I wrote a piece called the “Road to Hell”, which is a series of complex questions about ethics and in the middle of it I asked: “Would you work for a manufacturer who used child labour to make T-shirts?” In a class of 20 kids, none would work for anybody who uses child labour. The final question is: “Would you work for a manufacturer whose product could cause the death of the user like cigarettes?” In that question, half the kids said that they would. They said that because people know that cigarettes cause cancer and that they could die, they choose to do it, which is fine. But why do you want to be part of that? Suppose it is true that people know that they may die and that it is their responsibility, why do you want to have anything to do with designing a cigarette package even as a consequence that somebody is aware? Sometimes people don’t think things through – they are willing to participate in somebody’s death but they are not willing to do work that employs child labour. I don’t get it!

Massimo: That’s funny because I designed a lot of cigarette packages long before anybody said that it could kill you.

Milton: I think it is a tough question because, besides the unintended consequences, very often you don’t know the consequences of what you do.

Massimo: You mentioned this intriguing issue of the rational versus the passionate or romantic earlier.

Milton: A colleague of mine went to the Mothball a few weeks ago. It is an event where people stand on a platform and just tell a story of about five or ten minutes long on any topic. She was amazed at how emotional she was listening to the stories. This is as direct an experience as you can get: one person by themselves, telling a story, that’s all. It is also a good example of there being form and content in every experience. The content is what the narrative is, what the story is. The form is the way it was told, which is the person that told the story. In every case there are four options: an interesting story badly told; an interesting story told interestingly; a bad story told badly; and a bad story told interestingly. The last is the most mysterious part: a person can tell you the stupidest story, a story that has virtually no content, but you are fascinated because of its form, that is the way they tell it. Everything we do is divided that way, every job you ever do. Either you have a good piece of material to work on and you do an excellent job of it, or else you have a terrible or ordinary thing to work on and you transform it. Of course, that is what designers really get paid to do more often than not – to take ordinary content, an ordinary service, bank or anything, and make it seem like something else. The magic occurs when you can’t tell the difference between form and content: when the distinction between the narrative and its expression is not separate. When we say that could not have been done any other way. Those are the hardest to do. I think that the longer you are in the field and the more ambitious you are, the more you aspire to that objective.

Massimo: That leads to the issue of subjectivity and objectivity again. In design, I always try to be as objective as I can toward the content, although even objectivity is subjective. Nonetheless, I look for objectivity and like to be as transparent as possible. The issue of style never really comes to my mind. In fact, I negated the search for style from the very beginning. Style in our profession is like handwriting. You might control your handwriting in the beginning to a certain extent, but in the end it goes its own way, becoming what it wants to be, what it has to be. When style prevails over the content or task, I think it is detrimental as it becomes contrived.

Milton: I would agree to a large extent, but the interesting thing about style for me is style of thought. Style of thought is a way of thinking. How do you think about things? There is a distinction in style in the way that people think – some think obliquely, some surrealistically, some in terms of harmony, and every other way as well. You are quite right that it gets disturbing when somebody approaches something with a style in mind as opposed to the style emerging from the act of doing the work. However, there is no question about there being a style of the moment. If you are young and want to work, in most cases you have to work within the vernacular of the moment. Your work must look like other work of its period. If you introduce an entirely new way of working, you will be isolated or marginalised.

Massimo: Sometimes you might see trends reflected in certain solutions and things that you do. If it is too trendy, you must throw it away because you don’t want to be caught in that trap. Lella is very good at pointing trends out all the time.

Milton: It also depends on what products you are in. If you are not conscious of trends, you should not be in the design business. I mean trends are what the design business lives on. Fashion lives on trends.

Massimo: Fashion lives on trends, but not design.

Milton: Typography is trendy. All this stuff is trendy because they are of the moment. On the other hand there are those things that you hope will transcend their mobility, but that is not much of the field. Most of the field is based on acknowledging what is around and responding to it – that is the biggest part of the work.

Massimo: In my work, I really react strongly to clients in explaining why it is important that something is not trendy because I feel a responsibility toward the client to design something that is going to last a long time and doesn’t have to be thrown away in a few years from now.

Milton: You are lucky that you have been able to build a position that is about durability and not trendiness. It is about values that seem enduring and that somebody can depend on, as it will not vanish or look stupid next year. But that is not actually a position that many can take – it is a rare position.

Massimo: There is a moral imperative for designers that are dedicated to these issues to convey this issue to their clients. It is partly the role and responsibility of the designer towards themselves and the company, the products, the clients and the market not to do things that are trashable next year.

Milton: When you use the term trashy, I would suggest that not all trendy things are necessarily trash.

Massimo: Trendiness is trash because next year, when it is over, it becomes trash right away!