Wes Craven wasn’t the only rebel at Wheaton. Many students in the 1960s and 1970s echoed his cultural critique.

Much of the dissent centered on the mandatory ROTC program at the college. Support for ROTC weakened in the mid-1960s, as did support for the elaborately staged annual Veterans Day chapel services and the regular features in The Record on the exploits of the “Crusader Battalion.” After one Veterans Day chapel service in which 550 cadets marched into Edman Chapel in full military dress, a student wrote that it was “an example of this continual attempt to condition our decision—so that it is hardly a decision at all. God and country are whispered to us in the same breath. We march, guns in hand, to ‘Onward Christian Soldiers.’” Another student provocatively asked, “You know where else they have May-day military exhibitions?”

When Armerding’s administration told antiwar students that “You didn’t have to come to Wheaton,” one student retorted, “Must we cease to think, to evaluate upon admission to the college?” The dissenting students complained that “the administration has done its best to keep honest critics out of official school functions, and off the chapel platform. The admissions office has been careful not to admit too many of the more radical types.” “We had better start listening to the very ones we are turning away,” a 1974 student complained. “If not, we may never wake up.” The result was “so many basically lonely people among the students and faculty of Wheaton College.”

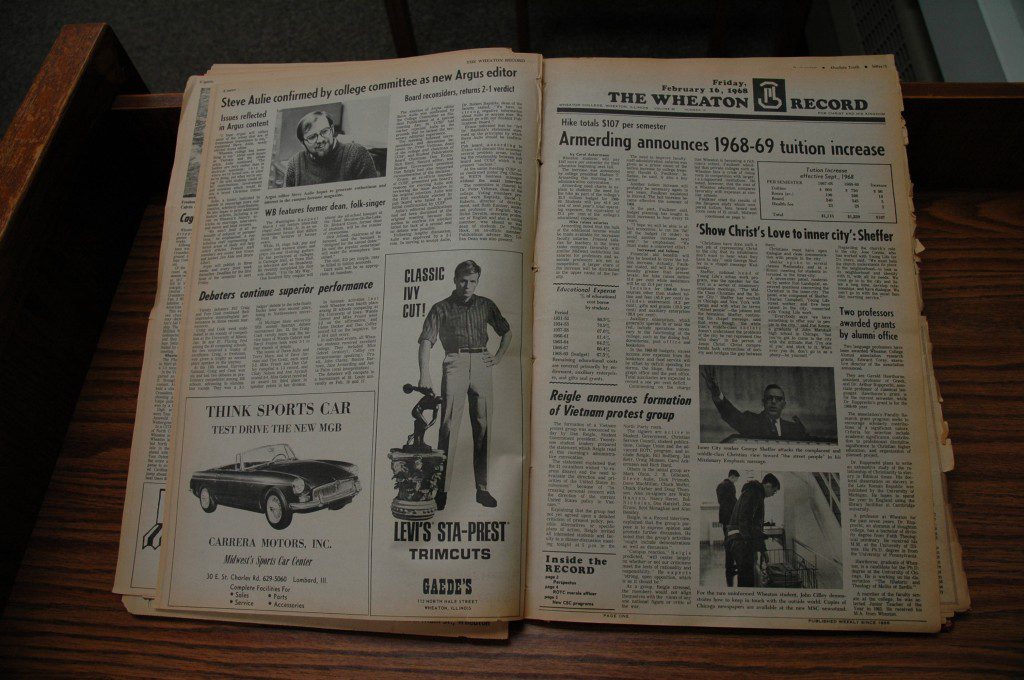

The campus newspaper, the Wheaton Record, published regular editorials and letters condemning fundamentalist insularity and calling for social action. They heralded a new age of evangelicalism that would send churches and workers back to the cities from the suburbs. Reporters wrote weekly articles on students’ participation in the Peace Corps, the National Student Association, and the Model United Nations. The newspaper’s editors published elaborate spreads of Wheaton students protesting for civil rights in Selma. They denounced “the coercion from the far right” upon Wheaton from donors. They protested presidential candidate Barry Goldwater’s 1964 appearance on campus and campaigned for Lyndon Johnson’s candidacy, purchasing a half-page ad in The Record that featured 120 signatures.

Many of these signatures and dissenting articles came from students and faculty with ties to the nascent social science division, a haven for progressives seeking some measure of distance from the conservative evangelical subculture. Students and faculty in the social sciences dominated the Clapham Society, a group of self-proclaimed “liberal” students, who vehemently argued against capital punishment, nuclear proliferation, elements of free enterprise, and invited Democratic Party candidates to speak to their club. A succession of progressive clubs—Social Action Forum, Americans for Democratic Action, the Young Democrats, and the Jonathan Blanchard Association—carried on this progressive tradition through the 1980s.

The latter organization strategically used the memory of Wheaton’s founding president, a stalwart abolitionist and economic reformer. Claiming to be the true heirs of Blanchard, progressive students in 1970 wrote a headline in a parody newspaper that read, “Blanchard Rejected by Admissions; Bearded Founder Not Welcome Here.” The reasons: Blanchard’s views on civil rights, postmillennialism, government land grants, facial hair, and pacifism. Longing to reclaim Blanchard’s legacy, students worried that their college had become “an introspective island in a world desperate for action.” The sixties had finally found its way to Wheaton.