A post by guest contributor, Eugene R. Schlesinger, Marquette University

It’s hard to find something that raises the hackles of Evangelical Christians quicker than the suggestion that the Eucharist is a sacrifice offered to God, unless it’s the suggestion that in addition to being a sacrifice, it is the sacrifice of Christ offered to God. Is this not the height of the vain superstitions from which the Reformers purified the church? Doesn’t such an idea call into doubt the sufficiency of Christ’s work on the cross for human salvation? Didn’t Anglicans in particular reject this idea when Article Thirty-One of the Thirty-Nine Articles of Religion said:

The Offering of Christ once made in that perfect redemption, propitiation, and satisfaction, for all the sins of the whole world, both original and actual; and there is none other satisfaction for sin, but that alone. Wherefore the sacrifices of Masses, in the which it was commonly said, that the Priest did offer Christ for the quick and the dead, to have remission of pain or guilt, were blasphemous fables, and dangerous deceits?

Well, maybe. But to my mind these questions are not the point. I am not going to address them directly. Instead, I want to do a bit of ressourcement—a retrieval of Scripture, the Church Fathers, and the Liturgy, to establish not only that the Eucharist is a sacrifice, and has been understood that way from the beginning, but that recovering the notion of eucharistic sacrifice is important for Evangelical Christians precisely because of a concern about the sufficiency of Christ’s sacrifice.

Sacrifice at the Origins of the Eucharist

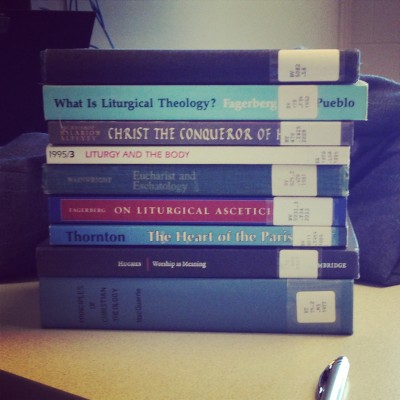

So, first, my claim that the Eucharist has been understood as a sacrifice from the very beginning. Rather than reinvent the wheel here, allow me to refer readers to three important studies: Kenneth Stevenson’s Eucharist and Offering (Pueblo, 1986); Andrew McGowan’s Ascetic Eucharists (Oxford, 1999), and Rowan Williams’s Eucharistic Sacrifice: The Roots of a Metaphor (Grove, 1982). These books show just how early in the tradition the Eucharist was discussed as a sacrifice. In fact, it was sometimes described as a sacrifice without any explicit mention of Christ’s body and blood, or the sacrifice of the cross.

McGowan, in particular demonstrates that it was inevitable for the Eucharist to be conceived as a sacrifice because of its character as a meal in antiquity. Pretty much any public meals in the Græco-Roman milieu were inextricable from sacrifices. This, of course, recalls Paul’s concerns about meat sacrificed to idols when he writes to the Corinthians (1 Corinthians 10:1-22). More than this, though, when we read Paul’s contrast between the Table of the Lord and the Table of the Demons in 1 Corinthians 10:18-22 with this knowledge in the background, we see that Paul is actually contrasting one sacrificial meal with another. Christians don’t partake in sacrificial meals associated with demons because they take part in a sacrificial meal associated with Christ.

Augustine and True Sacrifice

The contrast between the Eucharist and sacrifices offered to demons is also central to Augustine of Hippo’s thought. Augustine has inherited a long tradition of thinking of the Eucharist in sacrificial terms. What’s especially interesting, though, is this: his use of sacrificial language is limited almost entirely to contexts where he is opposing worship offered to demons (e.g., De Trinitate IV and XIII), or speaking about the Eucharist (Confessions IX, Sermons 227 and 272), or both (City of God X, Confessions X, Sermon 198). In other contexts, he uses other concepts to describe Christ’s death. Sacrifice, though, was especially suited to his anti-demon polemic and to his eucharistic thought.

As he explains in book 10 of City of God, sacrifice should be offered to God alone, and not to demons. He was particularly concerned with the practice of theurgy, which, according to Platonists such as Porphyry and Apuleius, would allow its practitioners to be purified by means of sacrificial offerings designed to secure the help of demons. In contrast to sacrifices offered to demons, Augustine insists that Christians have but one sacrifice, which is Christ’s, and that only God should receive sacrifice.

He further explains, by appealing to the Old Testament (e.g., Psalm 51), that true sacrifice is a matter of the heart. A visible and material gift is given as a sacramentum of the invisible sacrifice that God truly requires. Indeed, a true sacrifice is any act of mercy that is undertaken in order to bind together humanity with God in a holy fellowship so that we might be truly blessed (City of God, X.6). He goes further, though, to explain that the one true sacrifice was offered by Christ on the cross so that he might be the head of his body the church, and so that the whole redeemed city could be offered to God by him as the high priest.

That last transition is an important one, because it shows that for Augustine sacrifice is not just something that happened to the historical Jesus, but something that is going to happen to the church as a whole. He conceives of our final salvation as a sacrifice where we are offered to God by Christ. And he understands this offering to be at one with Christ’s sacrifice on the cross. The key insight behind this idea is Augustine’s understanding of the church as the totus Christus, the whole Christ, head and members.

Augustine’s thought here is, of course, deeply indebted to the Pauline image of the church as the body of Christ (e.g., 1 Corinthians 10 – 12; Ephesians 1:15-23). Suffice it to say that for Augustine, salvation is a matter of us returning to God, and that this return happens because we are united to Christ as members of his body. Sacrifice is one of the ways that he talks about that return.

We need to take two more steps to get where we’re going with this. First, immediately after he talks about the church as a whole being offered as a sacrifice to God, he also says that this sacrifice is the one offered on Christian altars, namely the Eucharist (City of God, X.6). Later in the same book, he’ll say that the Eucharist is a daily sacramentum of Christ’s sacrifice, through which the church learns to offer itself (City of God, X.20). This is important, because earlier he identifies the pious acts and ethical lives of Christians as sacrifices (City of God, X.3). Once more this is a very Pauline idea. In Romans 12:1-2, Paul begins the entire ethical section of the letter by describing ethics as a sacrifice offered to God.

Second, because of all the work he’s just done with the totus Christus, such that the sacrifice of the cross, of the whole church, and of the Eucharist are really one sacrifice of Christ, the lives of the faithful are themselves interior to the sacrifice of Christ. This is because the faithful are Christ’s members.

Conclusion: Eucharistic Sacrifice or Semi-Pelagianism

Here’s the point to which I’ve been driving, Augustine provides us with a way of synthesizing Romans 12:1, “Offer your bodies as a living sacrifice,” with 1 Corinthians 10:16-17, “The bread that we break, is it not a sharing in the body of Christ? Because there is one bread, we who are many are one body, for we all partake of the one bread.” And this synthesis is vital. Because it allows us to talk about our moral behavior in a way that is connected with Christ’s one sacrifice. Apart from a synthesis like that, we have two options before us. Either we envision spiritual benefits coming to us from a source other than Christ’s sacrifice, or we completely sever any ethical dimension from Christianity.

If the Eucharist spiritually benefits us, it must, somehow, be Christ’s sacrifice, because this is the only source of salvation. If our ethical lives are of spiritual benefit, they must be connected to Christ’s sacrifice, otherwise we are left with a Pelagianism where our moral conduct benefits us apart from grace, or with a semi-Pelagianism where our moral conduct is purely a response to grace. The Augustinian account of eucharistic sacrifice I’ve sketched here allows us to uphold the benefit of the Eucharist and the importance of our moral lives, even as it upholds the bedrock Evangelical commitment that salvation is to be found only in the sacrifice of Christ.

The Eucharist is not a repetition of Calvary, and it’s important to realize that this has never been the teaching of any church. The Eucharist is not a re-sacrificing of Christ any more than our moral lives are a re-sacrifice of Christ. There is but one sacrifice which Christ offered once for all. It is through this sacrifice that he returns us to God. And in the eucharistic sacrifice, he brings us and our lives into that one sacrifice so that through him we may once more come to God. Through his one sacrifice, he transforms our lives into a sacrifice pleasing to God, a sacrifice which is only pleasing to God because it is united to his own.

Eugene R. Schlesinger is a Rev. John P. Raynor Fellow at Marquette University, where he is completing his dissertation, “Ite, Missa Est! A Missional Liturgical Ecclesiology.” He lives in Milwaukee with his wife and children.