See How a Single Cell Dies in Gory, Intricate Detail

Today alone, some 50 billion cellular corpses will pile up inside you — and somebody has to clean them up.

Scientists have long known that special immune cells called phagocytes serve as the body’s waste management crew, tirelessly patrolling your tissues and hoovering up remnants of dead cells, invading bacteria and, sometimes, tattoo ink. Still, how exactly these amoeba-like phagocytes do their job remains somewhat mysterious.

In a paper published March 19 in the journal Nature Cell Biology, researchers added a new piece to the puzzle of how cells dispose of their dead. By watching an unusual cell death process over and over in a microscopic worm, biologists from The Rockefeller University have discovered that some cells rip themselves apart bit-by-bit in order to attract certain specialized proteins in phagocytes that will gobble them up and carry them away.

Watching cellular suicide

In the new study, researchers watched cells grow and die inside several specimens of Caenorhabditis elegans, a microscopic roundworm regularly used in scientific experiments. The team focused on a special type of cell called the tail-spike cell, identifiable by a long, pointed tail like you might see in a child's drawing of a devil. Roundwormsemploy these cells as scaffolding while forming their own tails; after a worm's tail is fully grown, the tail-spike cells heave a sigh and self-destruct through apoptosis.

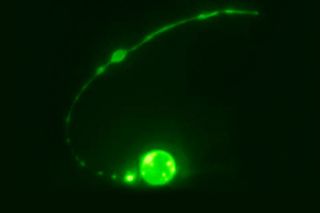

Watching through a custom-built microscope, the researchers captured this moment of cell death in 14 different worm specimens. As the dying cell slowly ripped itself into pieces, the researchers saw an unusual and intricate process unfold.

"Curiously, the middle of the cell is spliced out first," lead study author Piya Ghose, a postdoctoral fellow at The Rockefeller University in New York City, said in a statement.

After the cell's main core split apart from its spiky tail, the two sections began to degenerate separately. While the core rolled up into a sphere and slowly disintegrated, the tail began to break up into little, bead-like lumps and the pointed tip retracted into a ball. Eventually, phagocytes descended to engulf the little-bitty pieces. The whole process took about three hours.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

A pattern in the victims

Wondering whether this was a fluke or a process common to many cell types, the researchers turned their microscope to another complex cell — a neuron that only survives in male roundworms — and watched the death unfold. Sure enough, the neuron died and disintegrated in a series of separate stages, just as the tail-spike cell had.

"Since we see this phenomenon in two different cell types with complicated shapes, it is conceivable that similar death events occur in many animals, and perhaps even in human disease," study co-author Shai Shaham, the head of The Rockefeller University's Laboratory of Developmental Genetics, said in a statement.

Studying this process allowed Shaham and his team to identify specific proteins involved in specific phases of cellular corpse disposal. A protein called EFF-1, for example, appeared to be crucial in corpse-cleanup by allowing phagocytes to seal dead cell remnants within its encircling pseudopods, or makeshift arms, enabling them to quickly scarf down the pieces.

Mutations in this protein resulted in a dangerous breakdown of dead cell cleanup, the researchers wrote. Further investigation into these processes could help researchers identify where and why phagocytosis breaks down in humans.

"There is a lot we don't understand about this remarkable death process," Shaham said, "and we are hot on the trail of additional players."

Originally published on Live Science.

Brandon is the space/physics editor at Live Science. His writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. He enjoys writing most about space, geoscience and the mysteries of the universe.