The 2016 presidential election wasn’t kind to the news media. While some journalists did their finest work—among them Washington Post reporter David Fahrenthold, with his Pulitzer-worthy investigation into the Trump Foundation’s finances, and Fox News anchor Chris Wallace, with his skillful questioning in the final debate—many of the pundits, pollsters, and political reporters who covered the campaign were chastened by the fact that they never saw Trump’s victory coming. “The news media by and large missed what was happening all around it, and it was the story of a lifetime,” observed Jim Rutenberg, of the New York Times, in a postmortem that was published on November 9. One day earlier, on Election Day, the newspaper of record had put Donald Trump’s chances of winning the presidency at 15 percent.

One of the few journalists who were not caught off guard when the returns came in was Dan Rather, who had insisted from the very beginning, and throughout the tumultuous campaign, that Trump should not be underestimated. A little more than two weeks before Election Day, when conventional wisdom held that the race was all but over, Rather went on CNN’s Reliable Sources to warn that “talk about a sweep for Hillary Clinton and a so-called mandate is way premature.” Laying out a scenario that proved to be eerily prescient, he noted that if white men and “silent voters who don’t show up in the polls” turned out in great numbers, and if traditional blue-collar Democrats swung right, Trump could win. “I’m reminded of the old saying in Texas and Louisiana, ‘Don’t taunt the alligator until after you cross the creek,’ ” he added.

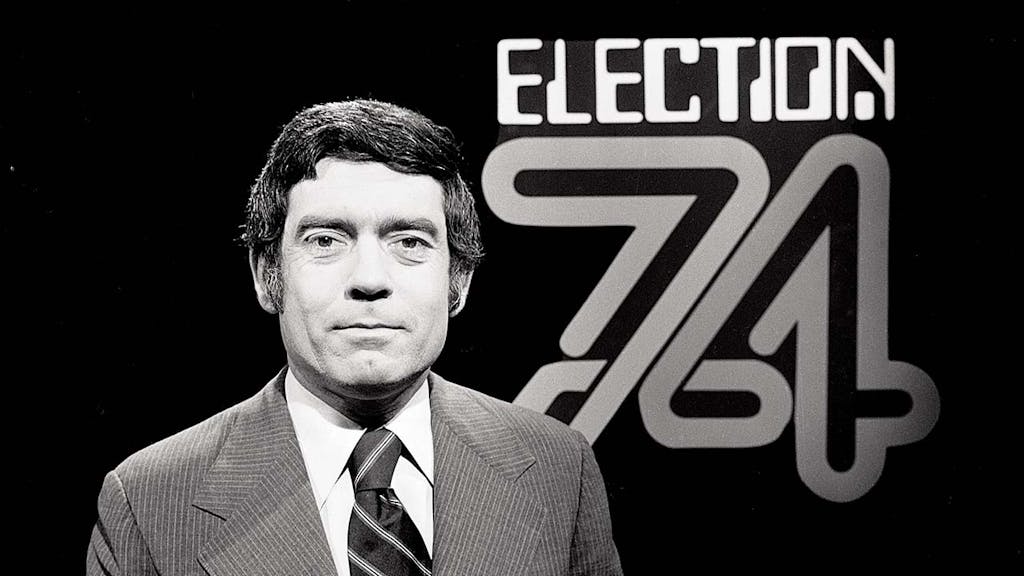

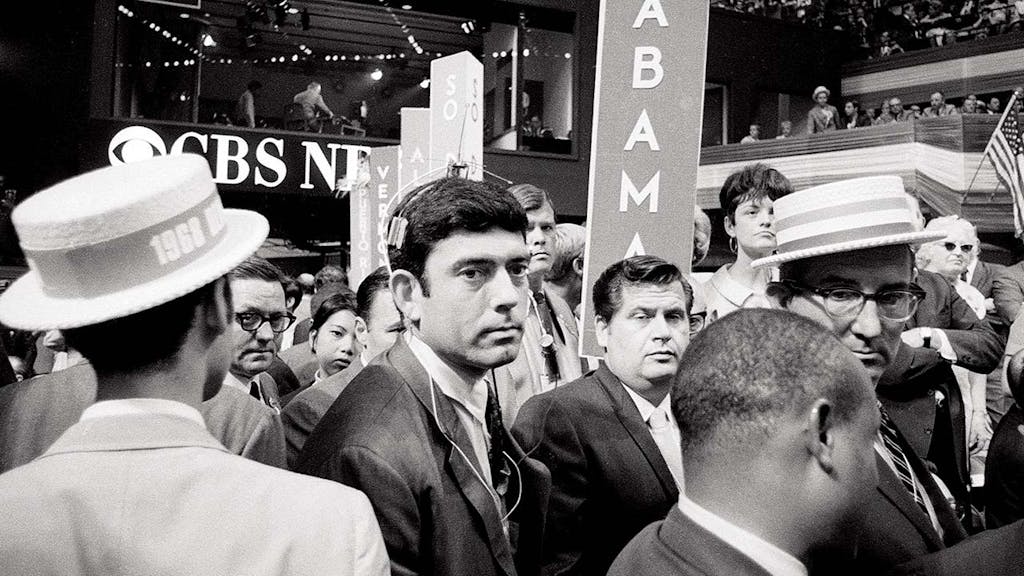

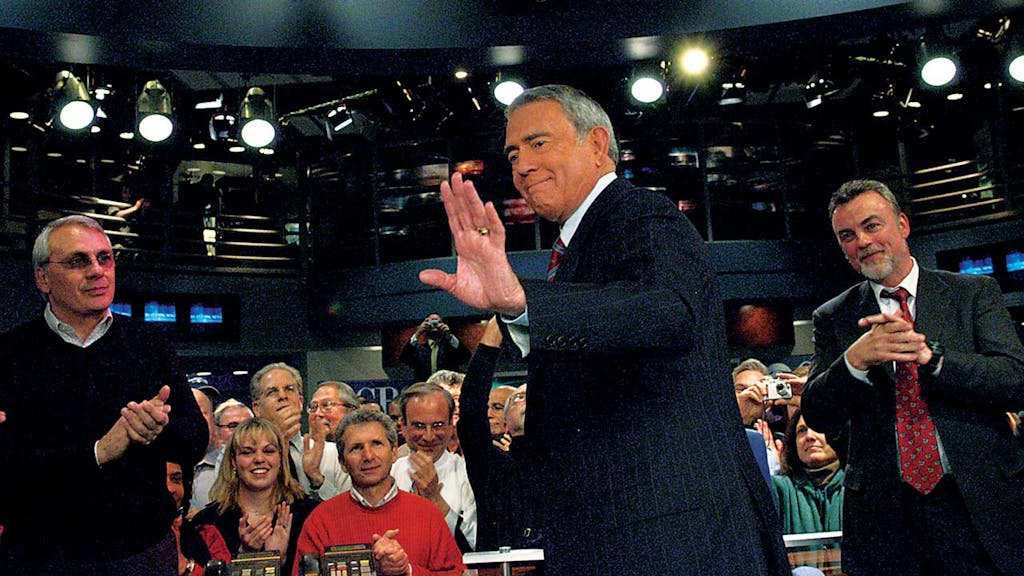

During the nearly quarter century that Rather anchored the CBS Evening News, he was one of the defining voices of his generation, crisscrossing the globe to report from war zones and natural disasters, and as a reporter in the field, he almost always outshone the competition. There was his live coverage of the JFK assassination from Dallas; his composure after being slugged by security guards—while the cameras were rolling—at the 1968 Democratic convention; his famously combative exchange with Richard Nixon at the height of the Watergate investigation, in 1974; his grilling of vice president George H. W. Bush about the Iran-Contra Affair, in 1988; his steady, reassuring presence after the Twin Towers fell, in 2001; and his exclusive interview with Saddam Hussein shortly before the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq two years later. But when he left CBS in 2006 following questions about the accuracy of a 60 Minutes II segment on George W. Bush’s National Guard service, his legacy was suddenly thrown into jeopardy. He kept busy on Mark Cuban’s cable network, HDNet (relaunched as AXS TV in 2012), but in the years that followed his departure from the nightly news, he was no longer at the center of the conversation.

Then something unexpected happened in the heat of the 2016 election: Rather found his voice again. On Facebook, he began posting eloquent, often spirited meditations on the presidential race and the direction of America today. “To anyone who still pretends this is a normal election of Republican against Democrat, history is watching,” he wrote on August 9. “And I suspect its verdict will be harsh.” His posts—by turn outraged, optimistic, troubled, patriotic—struck a chord. Though he was entirely unfamiliar with the medium, the onetime radio newsman found a large and devoted following. One missive, which focused on Trump’s suggestion that “Second Amendment people” could take action if Clinton were elected, reportedly reached an audience of some twenty million. The Daily Beast soon christened him “the only good newsman on Facebook,” and of Rather’s viral posts, a news editor, Ben Collins, wrote, “Nobody seems to know why they’re catching fire, and Rather is not interested in precisely why. But here’s one good reason: Each post is filled with equal parts foreboding and hope.”

And so, at the age of 85, Rather is back. This time, he’s not sitting behind the anchor desk but instead at his computer, where he tries to make sense, day by day, of what is certain to be the most unpredictable presidency in modern American politics. Unencumbered by the trappings of the network news, with the ratings wars behind him, he is free, finally, to speak his mind.

Pamela Colloff: One of the greatest criticisms of the media after the election was that reporters—who largely live on the coasts—did not understand, or care to understand, places like Indiana or Michigan or, for that matter, Texas. Going forward, what should media organizations do differently when it comes to covering so-called flyover country?

Dan Rather: The criticism is valid. It’s something I find myself talking to other journalists about in the wee hours of the morning over an adult beverage. First, there’s no substitute for what used to be called “feet on the street,” which is just another way of saying that the only way to understand what’s going on “out there” is to go there. You have to go to the heart of the story, or get as close as you possibly can, whether it’s a combat zone halfway around the world or the American heartland. Unfortunately, the old business model for journalism doesn’t work anymore, so there are far fewer resources, and that’s had a profoundly negative effect on all aspects of journalism, including deep domestic reporting. Many reporters nowadays don’t really understand the middle of the country. Because I’m from Texas and because I’ve stayed connected to many people back home, I said right from the beginning, when Trump got in the race, “Don’t underestimate him.” I knew that some of the things he said during the election—many of them outrageous, repulsive things—would resonate with a lot of people. I thought he could win right up to the moment he did, because he had a path. He played to people’s fear, resentment, and, yes, some racial prejudices, and that was the path that he tread. Meanwhile, the Clinton campaign was basically tone-deaf about how this was resonating, and unfortunately, many in the press were tone-deaf as well.

PC: But Trump did more than just stoke fear and resentment, don’t you think? He had a very clear economic message, and he used that message to connect with his audience—in the heartland and beyond—in a powerful way.

DR: Absolutely agree. That was a very important part of it. He hit that note repeatedly, that globalization needs to be rethought. He understood that global economic forces, combined with major demographic changes in America, were making people worry—“How am I going to make a living? How are my kids going to make a living?”

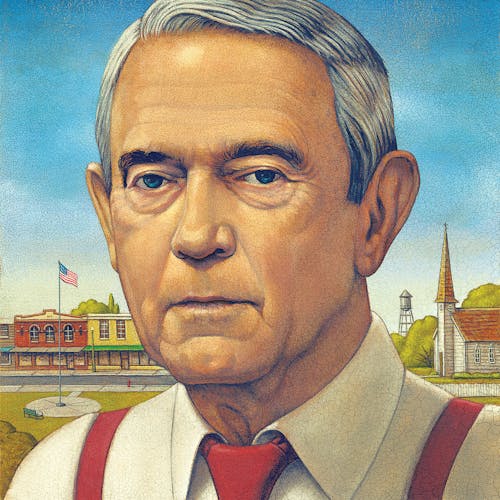

PC: In Wharton County, where you were born, Trump won by almost 69 percent. That’s a pretty remarkable number. What has, or hasn’t, changed about Wharton County? Why do you think Trump found such deep support there?

DR: Well, what hasn’t changed in Wharton County is that it places a high value on individuality. It places a high value on personal responsibility and on being able to provide for your family. But there is no understanding Texas—and there is certainly no understanding Wharton County—unless you understand how deeply people are tied to the land. Wharton County was at one time great cotton country, and then it became great rice country. But agriculture has changed so tremendously that there’s no doubt in my mind that people feel caught in a kind of economic time warp. So now there is uncertainty about whether you can provide for your family. There is a sense that a certain way of living has disappeared, or is in danger of disappearing.

PC: During the course of the campaign, what did the national media get wrong about Texas?

DR: I was slightly amused—maybe “bemused” would be the better word—with the stage in the campaign when people were saying that Hillary Clinton might carry the state. I never in my wildest imagination thought she would. In any election in Texas, strength is valued. I saw this when I was a young reporter coming up in Harris County. Whether it was a race for the school board or city council or county judge, the person who projected the most strength always won, even if he was a little less principled.

PC: Still, it seems notable how much of the state Clinton did win. Most people outside Texas consider it to be uniformly red, but she won virtually all the urban centers—Dallas, Houston, Austin, San Antonio, Laredo, and El Paso.

DR: The state is very clearly divided between urban and rural. And only the urban parts of the state are growing. So I do subscribe to the theory that Democrats will have increasingly better chances as the years go by—if they get their act together.

PC: You recently reflected on Facebook about Trump’s habit of misrepresenting the facts, as when he tweeted, “I won the popular vote if you deduct the millions of people who voted illegally.” You wrote, “In times like this, I sometimes try to imagine what my journalistic hero Edward R. Murrow would do.” How would Murrow have advised journalists to cover a falsehood propagated by the president-elect?

DR: Around the old Houston Chronicle newsroom, there was a saying: “Trust your mother, but cut the cards.” And that is what Ed Murrow believed. He always saw himself as an honest broker of information, as drained of bias and personal prejudice as is humanly possible. He had been known to say—and I heard him say it—“You can know all the facts and still not know the truth.” He wanted us to gather as many facts as we could, but then he wanted us to go a step further—to scrutinize the facts, connect the dots, and come up with an analysis. An example that Murrow used was from the McCarthy era. He’d explain that a story that read “Senator Joe McCarthy said there are hundreds, if not thousands, of communists in the State Department” is a factual story. But unless you also added that McCarthy never once named those people, and that he refused to name them, it’s not a true story. You see where I’m going with that?

PC: Yes, absolutely.

DR: Reporting must provide context and perspective. Murrow would have compared Trump’s statements with the demonstrable record and shown where there was conflict. Murrow hated hypocrisy. Whether he was covering foreign leaders or politicians in his own country, the question that was foremost in his mind was always “What’s the hypocrisy quotient in all of this?” He considered hypocrisy worse than bad chili. But there’s been a steady erosion of journalists willing to state obvious truths, such as “What this candidate says is just flat wrong.” I don’t excuse myself from this criticism, because you know the sort of grit in the gut that it takes to say, “You know, folks, what’s being said is demonstrably wrong, and this person knows it’s wrong. And that equals a lie.” There was a lot of discussion during the campaign about the fact that no one wanted to use the word “lie.” Everyone, including myself, was looking for metaphors for “lie.” Later in the campaign, reporters got more comfortable using the word, but there’s still some resistance. A central question—not just for journalists but for society as a whole—is, Have we moved into a post-truth political era, where facts no longer matter? I hope and pray that we have not, but there are some signs, unfortunately, that we have.

PC: If the truth becomes more subjective, the media may have difficulty staying relevant.

DR: That is a central challenge for journalists right now. You know, this quote did not originate with me, but I don’t think we can say it often enough. And that is, “Everybody is entitled to their own opinion, but they’re not entitled to their own facts.”

PC: Another challenge facing the media right now has to do with Wikileaks. When hacked emails are released, what should reporters do? Run them, ignore them, cherry-pick the most illuminating ones? What is our moral obligation considering the source of the material? And if we run them, don’t we encourage more hacking?

DR: I come back to Murrow’s words about context and perspective. Try to put the hacked emails into context; try to provide perspective. Part of what’s changed about journalism is that now there’s a deadline every nanosecond, and that places an undue emphasis on speed rather than on taking the time to figure out where the material is coming from and provide some context for it. I understand the argument “This is news—it’s all over the internet, it’s all over cable television—and if you want to be a part of the conversation, you’d better get into it right now.” So this dilemma will not be easily solved, particularly in today’s environment, where the emphasis is on being the fastest.

PC: Do you see any parallels between this campaign and others you’ve covered, like the 1968 election, for example? Or was 2016 a wholly new phenomenon?

DR: The first national election I covered was 1952, and that was the Eisenhower-Stevenson race. And I’ve been covering national campaigns since then. I’ve not missed one. Each presidential election is unique unto itself, but, yes, the closest that we’ve had to this election was in 1968, when it was Nixon versus Humphrey. First, Nixon spoke directly to the silent majority, which Trump did as well. Secondly, Nixon’s campaign had all kinds of so-called dog whistles, or coded racial messages. And third, Nixon sought to dominate any landscape that he occupied. Unlike Trump, he was a very poor orator, so there are great differences, but Nixon refined the practice of using modern television to cast his image. Nixon did this with television advertising, whereas Trump put himself at the front and center of the day’s news.

PC: Nixon also had a testy relationship with the press. Are there any other parallels?

DR: There were not nearly as many questions about Nixon as there were about Trump, but there were questions about whether he had the mental stability necessary to do the job. Nixon had that outburst with the press in California in 1962, and so there were some questions about whether he had the right personality and character to be president. But Nixon had been a congressman, a senator, and a two-term vice president, so he could make the argument that he was as well prepared for the presidency as anyone who had ever run for it. Trump did not have that argument to make.

PC: In October the Daily Beast ran an article called “How Dan Rather Became the Only Good Newsman on Facebook,” which talked about your mastery of the medium. Why did you decide to use Facebook as your megaphone? How is it different from TV?

DR: I have to acknowledge that I was slow to come to both Twitter and Facebook. I run a small news operation called News and Guts, which some people see as a joke, because it’s so small. It’s a company I formed when I left CBS News, and it has had ups and downs and roundabouts. But several people I work with told me that in order to be relevant, I had to be on social media. I was a man from another age, and it just didn’t appeal to me. But very quickly, I saw that they were right. If I wanted to be part of the conversation, it was imperative.

PC: Unlike most people on Facebook, you’re not afraid to go long. You write these perfectly crafted mini-essays, and people really respond to them.

DR: I just decided to write from my heart at whatever length I needed to, and if it failed, it failed. To my surprise, there was an audience for it. I’m still trying to get my head around it. Some posts that are widely shared reach three, maybe four, million people. Not every post does that, but we have built an audience. We now have more than one million followers. The exposure is not quite what the CBS Evening News was in its heyday, but that’s a lot of people. I never expected at this stage of life—I’m 85, going on 86—to have an audience that size. What I like about Facebook is that it’s a conversation. People react to what I’ve posted, and I react to them. Frankly, it’s one of the best things that’s happened to me in my whole career. That may be damning with faint praise. But I consider myself to be one of the luckiest humans walking the face of the earth. I started in print, wandered into radio, worked in television, and now I’m on the internet.

PC: Late in the evening on election night, you got on Facebook Live and began to talk extemporaneously about the returns. For someone like me, who grew up watching you on TV, it was fascinating; it was like you were updating the traditional idea of the anchorman. What kind of role would you say you’re trying to play on Facebook?

DR: To be perfectly honest with you, I’m not sure what role I’m playing. What I’m always trying to do is to be an honest broker of information. I’m trying to bring context and perspective to what’s happening, simply because I’ve lived a long time. I’ve been a few places and seen a few things—combat, natural disasters, elections, what have you. But that doesn’t mean I know everything. I never thought I’d see in my lifetime a candidate as divisive as Donald Trump sworn in as president.

PC: I recently spoke to your longtime producer Mary Mapes and learned about a little-known act of kindness that you performed many years ago for a young Afghan translator, who worked for you in Kabul. From what I understand, this man is now an American citizen and lives in Dallas. Can you tell that story?

DR: I’ll be happy to oblige, but I’m not the hero of this story—Mary is. She and I reached Kabul at the same time the first American forces arrived there in the wake of the 2001 invasion of Afghanistan. It was a hair-raising trip. We landed at Bagram Air Base, and right away we needed a translator. We ran across this young man who was working for the Red Cross, and his English was perfect, so we hired him on the spot. Now, working with translators in a place like Afghanistan—or Indonesia, Somalia, or Yemen—is a risky business. People can betray you in small ways, such as stealing your transistor radio and making it appear like somebody else stole it, or in much more serious ways by exposing you to bad elements in their society. It’s extremely difficult to find anyone you can trust even at a low level, much less the way we did with this young man, when we literally trusted him with our lives.

We were in and out of Afghanistan a number of times over the next year and a half, and he did a wonderful job for us. He turned out to be a really intelligent young man and one of the most decent people you can imagine. Mary and I decided we had to find a way to bring him to the States and get him in school. He was already very well educated—the kind of person who if you gave him an SAT test, he would knock it through the roof—but had not been able to finish his studies. We made arrangements to bring him to Dallas, and he lived in Mary’s garage apartment. How she did this, I don’t know, but she managed to get him into Southern Methodist University, where he studied environmental studies and engineering.

PC: Mary said you would be modest about this but told me that you helped grease the wheels to get him over here and that you paid a large portion of his tuition.

DR: Getting a visa was not easy at that time; it took a little bit of back channeling to help arrange that. I’m quite pleased that we were able to help him. He’s a productive member of society now, and I’m very proud of him.

PC: Let me shift gears for a moment. The Texas Legislature will have just gone into session when this article hits newsstands. You’ve spoken passionately about the need to invest in our public schools, because many high school students aren’t ready for college. Any advice you’d give to our lawmakers?

DR: You know that I love Texas in a deep and abiding way. I’m not just from Texas, I am of Texas. And I am a product of Texas public schools. From first grade—we didn’t have kindergarten—all the way through college, I attended only public schools. And the importance that public schools play in this great experiment we call America simply cannot be overstated. But the last time I checked, Texas schools ranked forty-third in the nation. I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again, because I believe it so strongly: God did not put Texans on earth to be forty-third in anything, much less something as important as schools. I fully understand all the arguments against public schools, and I understand many well-intentioned and decent people have a different view. If you can strengthen charter schools and home schools at the same time, that’s fine. But public schools are the red beating heart of Texas. And it’s just appalling what’s happened in recent years.

If you looked at this problem from a business standpoint—and I’m not suggesting that’s the only way you should look at it—we’re not educating our workforce well enough to train them for the jobs of today or tomorrow, or to sustain Texas’s economic growth. It’s not happening, and we know it’s not happening. That frustrates the daylights out of me. I think it’s imperative that lawmakers make improving our public schools priority number one, two, and three.

PC: One last question. You have traveled to every corner of the world and done everything I can think of that a journalist would possibly want to do. So what’s left on your bucket list? What do you still want to do that you haven’t done?

DR: [Long pause.] I want to be a great journalist. That’s what I set out to do. That is my North Star. It’s true, I’ve been a lot of places and done a lot of things. But I’m still trying, still fighting, still striving to be a great reporter. I know in my heart of hearts that I’ve never been as good as I ought to be, or as good as I should’ve been. But that’s what drives me: trying to be a great journalist. One of the reasons I got into journalism was that I wanted to be a part of something bigger than myself. I wanted to contribute in some small, wee, microscopic way. Fortunately, I still have my health—who knows for how long—because I still want to contribute. I want the work to matter. T

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Dan Rather