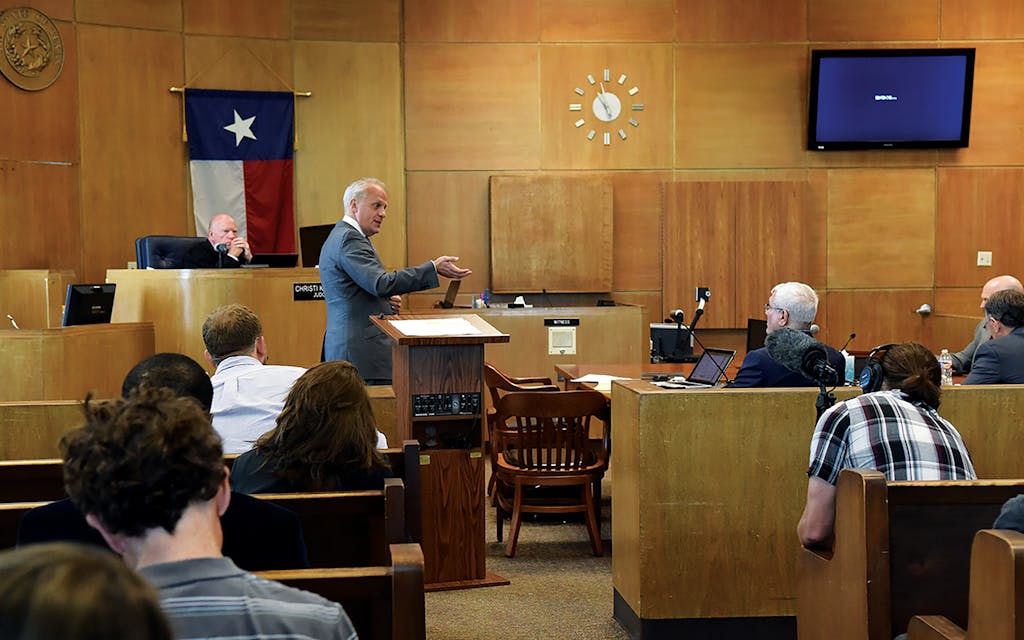

June 6, 2016, convicted murderer Kerry Max Cook walked into a Tyler courtroom. The sixty-year-old was dressed in black, his silver hair trimmed short. Cook’s eyes, dark and nervous, shot around the wood-paneled chamber, which was filling rapidly. Local news reporters and a documentary-film crew from New York were setting up cameras and microphones. Cook caught sight of three men in the audience, men who had once been convicted criminals themselves: Billy Smith, Michael Morton, and A. B. Butler Jr. All three, famously, had been proved innocent of their alleged crimes after serving a collective sixty years behind bars. They had come from miles away to attend this hearing, and Cook walked over to greet them. Smiling, the three stood to shake his hand. Morton clapped him on the shoulder.

Cook, who has a big, square face, smiled too. He had fought for almost four decades to get to this moment. In 1978 a jury found him guilty of the murder of Linda Jo Edwards, a 22-year-old Tyler secretary whose body was discovered in her apartment bludgeoned and mutilated. The case confounded the city’s investigators and prosecutors with its gruesomeness, and Cook became known as a monster and a deviant, the most notorious killer in Smith County. Over the years, the county’s prosecutors had sought—four different times—to send Cook to death row.

But Cook had always claimed he was innocent, saying he’d had no motive to kill Edwards. Though his protests garnered little attention early on, eventually his case attracted a number of sympathizers and advocates, some who reexamined the evidence and others who represented him in court for his numerous appeals. Cook and his supporters had clashed fiercely with Smith County, making repeated headlines, and he had become a celebrity worldwide, an indelible symbol—at least outside Tyler—of the overreach of the Texas criminal justice system. His story was dramatized in both a play and a movie, and Cook grew into an anti–death penalty hero, accumulating thousands of friends and followers on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter; one of his fans, Madonna, had recently posted a short video made by New York fashion photographer Steven Klein about Cook. “Join me and Steven Klein,” she wrote, “in his long struggle to prove his innocence and clear his name.”

Now, finally, Cook had been granted this hearing, to determine whether his conviction should be thrown out at last. Scanning the room, he recognized many of the players who had moved his case through the courts. Up front was Scott Howe, who had represented him in the eighties, sitting next to Paul Nugent, who had done so in the nineties. In the back was Nugent’s adversary, David Dobbs, the prosecutor who, for eight years, had tried relentlessly to have Cook executed. Also present was Jim McCloskey, an investigator for Cook whose research had led to an exhaustive report naming another man—Edwards’s boyfriend—as her killer.

That man, James Mayfield, was in the courthouse too, waiting in a hallway for his turn to testify. Forty years earlier, Mayfield had been a brazen lothario, carrying on a seventeen-month affair with Edwards—who was half his age—under his wife’s nose. On this day, though, the 82-year-old sat quietly, wearing a green T-shirt and spectacles, looking tired.

Cook took a seat at a table in front of the judge’s dais, next to his lawyers, Gary Udashen, the president of the board of directors of the Innocence Project of Texas, and Nina Morrison, from the national Innocence Project. Across from them were the district attorney of Smith County, Matt Bingham, and two assistants. The six sat in awkward silence as they waited for the judge to appear. Finally Cook whispered something to Morrison, putting his arm around her shoulder. She leaned in and whispered something back.

Moments later, at nine-thirty, Judge Jack Carter climbed into his seat, banged his gavel, and announced to the world what Cook and his lawyers already knew. Peering over the bench, the judge declared in a deep East Texas accent that, as of that morning, the state had agreed to recommend that Cook’s conviction be set aside. He was, for all practical purposes, exonerated.

Quickly, Udashen, whose graying eyebrows and glasses give him an owlish look, rose from his seat and addressed the court. He and Bingham had struck a deal, he explained: in return for the prosecution’s acknowledging that Cook’s due process rights had been violated by the state’s use of false testimony in earlier trials, the defense had agreed to relinquish six of its eight claims, including several that alleged prosecutorial misconduct. The defense would still fight for Cook to be declared “actually innocent” of the murder, a legal claim for which his lawyers would need to offer powerful new evidence. If Cook was ruled actually innocent, he would be entitled to about $3 million in compensation for nineteen years behind bars.

Then Udashen’s words took a curious turn, at least to those familiar with his client’s long-standing battle with Smith County and its prosecutors: the lawyer began to praise Bingham for his openness and assistance. “We deal with these kinds of cases, and we deal with DAs around the country,” said Udashen, “and the ability of justice to be done in a case largely depends on the ability or the willingness of the DA to cooperate, to let us review their files. The way Mr. Bingham handled this is a model for how to deal with these types of situations.”

When Udashen finished, Bingham—a bald and bearded man who carries himself with the confidence of a successful prosecutor—stood and spoke briefly. He was followed by the judge, who announced that the agreement would go to the state’s highest criminal tribunal, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals, for approval. He excused the witnesses—there would be no testimony now—and declared that the hearing on Cook’s actual innocence would take place later that month. Then he banged his gavel. The whole thing was over in thirteen minutes.

Cook, who had remained impassive throughout, rose slowly. He hugged his lawyers and crossed into the gallery to embrace his wife, Sandy Pressey. Then, followed by the scrum of supporters and reporters, he made his way down the stairs and outside, where he stood in front of the courthouse to have his photo taken with his defense team, the three other exonerees, and his family. Cook seemed more impatient than exuberant, smiling thinly for the cameras. At one point he looked out over the milling crowd and watched as a stooped man with white hair and a walker made his way slowly down the sidewalk. It was Mayfield, heading toward an SUV that would take him home to Houston.

An hour later, at a celebratory lunch at Outback Steakhouse, Cook sat with a large group of lawyers and friends, listening as they told stories, laughed, and toasted one another for the day’s hard-earned results. It was the end of an era. Cook had arrived on death row in 1978 and was finally getting justice, like other Texas men who had been condemned to death before him and also won their freedom: Randall Dale Adams, Clarence Brandley, Ernest Willis, and Anthony Graves.

The day should have been the happiest of Cook’s life. But instead Cook seemed preoccupied, not quite present. Something was bothering him, and two days later, he wrote an email to his lawyers and several journalists to explain: he could not accept the praise that Udashen had heaped that day upon Bingham and, by extension, Bingham’s predecessors, who had sought his misery and death for so long. He was firing his lawyers, he declared. Then he posted the email on Facebook and followed it with a series of rants accusing his lawyers of collaborating with the enemy. His words grew more and more hysterical, until finally, Cook announced that he needed a new attorney, one who would help him withdraw the agreement and “restore me with a wrongful murder conviction.”

Even his closest supporters thought he was crazy. “I’m frankly devastated by this recent development,” wrote a blogger on a sympathetic criminal justice site. Around the country, observers scratched their heads, as did other exonerees, many of whom had also worked with Udashen and Morrison. What kind of person would fire two of the best lawyers in the country—and then ask to be given back his wrongful conviction? Who would sabotage an exoneration forged after 39 years of heartbreaking struggle?

Kerry Max Cook would. And he has his reasons.

Linda Jo Edwards was a tall, striking brunette who grew up on a farm in Bullard, a tiny town just south of Tyler. After high school, she traveled up the road to the city of 67,000 and landed a job as a library clerk at Texas Eastern University. Edwards liked living in the Rose Capital, which still had a small-town feel. In May 1977 she moved into a spare room of her friend Paula Rudolph’s place at the Embarcadero Apartments, a huge complex on the south side of town. Tyler, which had more than fifty Baptist churches, might have been a conservative city, but the Embarcadero was a place for young singles, and on her days off, Edwards would sit out at the pool, sunbathing and socializing. She had a bubbly personality, Rudolph would later remember. “She made you feel good when you walked in the room and she smiled and said hello to you.”

When Edwards was found dead in her room on the morning of June 10, 1977, the news sent shock waves across the city. Investigators found her body on the red-and-black carpet, naked from the waist down. She had been beaten in the head and stabbed more than twenty times in the face, neck, chest, back, and pelvis. Though they found no semen, officials figured she had been raped too, and it appeared that the killer had also cut off some hair and sliced out parts of her lower lip—as well as her entire vagina. One of her stockings appeared to be missing, a fact that investigators tried to make sense of. “We kind of figure he placed all the body parts in the hose and [took] it out,” lead detective Eddie Clark would surmise. It was the type of crazed crime committed in Southern California, not in East Texas, and not in the hometown of the Rose Queen and all-American football hero Earl Campbell.

Because there were no defensive wounds on Edwards and no signs of a struggle, the police suspected the victim had known her killer. Edwards’s roommate, in fact, told investigators that when she returned from a date at 12:45 a.m., she had seen a slender, tanned man in Edwards’s room whom she’d assumed was Edwards’s boyfriend, James Mayfield. The man had silver, medium-length hair, like Mayfield, and was wearing white shorts, which the tennis-playing Mayfield often did.

But when investigators spoke with Mayfield—who drove himself to the police station to give a statement that same afternoon—he said he had been at home the previous night, with his wife, Elfriede, and their daughter Luella. The married father of three, who until recently had been the head librarian at Texas Eastern, admitted he’d been having an affair with Edwards. But it was over, he stated, and they’d not had a tryst in three weeks. Luella confirmed her father’s alibi. Though the sixteen-year-old confessed feeling rage toward Edwards—she admitted threatening the woman’s life on several occasions—her feelings appeared to be those of a jealous teenager, not those of a killer.

In any event, the police theorized, the killing was so savage that it was inconceivable for a family man or a teenage daughter or a roommate to have carried it out. Three days after the murder, a team of investigators, led by Detective Clark, reached out to a psychologist to help them determine the type of person who would commit such a crime. Jerry Landrum had lent his expertise in previous criminal cases, and after poring over the crime-scene photos and visiting Edwards’s apartment, he provided a profile of the killer. The murderer, said Landrum, was a man between the ages of eighteen and thirty who was probably gay or bisexual, maybe a drug user, maybe impotent, and definitely introverted. He was “a sexually inadequate male with pathological hostility” toward women. He probably had an “abnormal relationship” with his mother and had also “seen a doctor for his extreme anxiety.”

Armed with the profile, the police focused their efforts on the apartment complex, going door to door to interview every resident and fingerprinting every man. When no one who fit the profile emerged and none of the fingerprints matched those in Edwards’s apartment, the Tyler Courier-Times, which had been publishing updates on the investigation, printed a public plea from the police department for help. But June turned to July, and Clark, who was spending every single day at the Embarcadero, couldn’t catch a break.

Then, on August 2, a truck driver who lived in the complex spotted Clark on the grounds and called him over to his apartment. The truck driver was named James Taylor, and Clark had already interviewed him. But Taylor had been doing some thinking. Back in April, he said, he had picked up a hitchhiker in Tyler and brought him back to his apartment, where the young man wound up crashing for a few days; he’d returned in early June for another stay. This man, said Taylor, matched some elements of the profile. He was 21 years old, his parents lived in nearby Jacksonville, and oddly enough, he had left town a few days after the murder. He was, Taylor noted, bisexual. His name was Kerry Max Cook.

Back at the station, Clark discovered that Cook had a criminal record. A fellow officer then made a stunning find: one of Cook’s fingerprints matched a print found on Edwards’s patio door. Cook was tracked to Port Arthur, where he was living with a girlfriend and tending bar, and flown to Tyler in handcuffs. The arrest made the front page of the Courier-Times. When the reporter asked an officer to speculate about Cook’s motive, the law agent demurred, then added that any attempt to do so was “so complicated it would take three or four hours to explain, and you still might not understand it.”

Cook was an outsider, a long-haired misfit who liked to dabble in drugs and experiment with his sexuality. Born in 1956, he was an Army brat who’d been raised in Europe with an older brother until 1972, when his family moved to Killeen and later Jacksonville, where his parents had grown up. He’d been an anxious, troubled youth who frequently fought with his parents: he’d run away from home several times, dropped out of the tenth grade, and stolen cars for joyrides. He’d been arrested several times as a juvenile—once he kicked in some store windows at a secondhand shop—and spent five months behind bars, where he said he’d been sexually abused by another inmate. He’d also made three trips to Rusk State Hospital, where he had cried for his mother at night. Staff members there had diagnosed Cook with “situational depression” and an “inadequate personality” and made several recommendations, including for Cook to “explore inordinate dependency on mother.” Cook fled Rusk and traveled around the country, sleeping on couches and bartending and dancing in strip clubs. At a time when homosexuality was illegal—the Supreme Court ruling that invalidated Texas’s sodomy law was still 26 years away—he’d spent several months in the gay bar scene in Dallas before winding up in Tyler.

Cook denied having anything to do with the murder, or even knowing Edwards. He offered an explanation for his fingerprint: Edwards sometimes undressed in front of her window, and one time during his stay with Taylor, he had leaned against the patio door to get a closer look. His story was corroborated by Taylor’s two nephews, who often came to visit at the apartment and had heard Cook talk about seeing Edwards naked.

Investigators were skeptical of Cook’s protestations. Besides the fingerprint, there was Cook’s rap sheet, as well as the fact that, according to Taylor, he was impotent (making him, in Clark’s assessment, “a very frustrated bisexual”). There was also the matter of Cook’s whereabouts on the night of the murder. A friend of Taylor’s, a hairdresser named Robert Hoehn, told the police that he had spent the evening with Cook and that the two had engaged in sex at Taylor’s apartment while watching The Sailor Who Fell From Grace With the Sea, an art movie that featured a cat mutilation scene. Afterward, Hoehn had taken Cook to get cigarettes and dropped him back off at the complex at about twelve-thirty—which would have given Cook enough time to kill Edwards before her roommate came home.

In addition, Edwards’s roommate was increasingly unsure that the man she’d seen that night was Mayfield. (In fact, at a September 1977 bond hearing she testified that it was definitely not him.) Most troubling of all for law enforcement officials, word came from the jail where Cook was housed that a fellow inmate there had heard him confess. Edward Scott Jackson, himself charged with murder, told investigators and A. D. Clark III, the district attorney on the case (no relation to the detective), that Cook had told him he’d killed Edwards.

The details added up to a highly disturbing picture, which prosecutors presented at Cook’s trial, in June 1978. Representing the state, Michael Thompson, aided by Thomas Dunn and Randy Gilbert, explained their theory: the sexually frustrated Cook, who had been aroused by the mutilation scene in the movie, had entered Edwards’s apartment and raped, killed, and mutilated her, cutting out body parts and stuffing them into her stocking, which he took with him. The theory was supported by a parade of witnesses, including the jailhouse informant, who testified that Cook had confessed to cutting the victim “in between her legs in a V shape.” Hoehn testified that Cook had been unable to perform sexually that night; a fingerprint expert testified that he had been able to date Cook’s print to within six to twelve hours of the murder; and Edwards’s roommate, despite not recognizing Cook at a pretrial hearing, pointed at him from the witness stand.

Cook’s parents had hired two lawyers, John Ament and LeRue Dixon III, whom they paid $500 to defend their son. Though the attorneys did their best to cast doubt on the state’s theory, their efforts were undermined by the crime-scene photos, which prosecutors insisted on showing the jury. (“After they put those sixty-six slides on the wall,” Ament would later recall, “school was out. The rest was an exercise in futility.”) The lawyers did not have the money to hire their own experts, nor could they compete with Thompson’s dramatic flair. “He was tall and gaunt and spoke with a dry, crackling voice,” said David Barron, who covered the case for the Courier-Times and the Tyler Morning Telegraph. “He looked like Ichabod Crane.” Confidently roaming the courtroom, Thompson called Cook a “little pervert” time and again, referring to his “lust for blood and perversion.” He even speculated that Cook had eaten Edwards’s body parts.

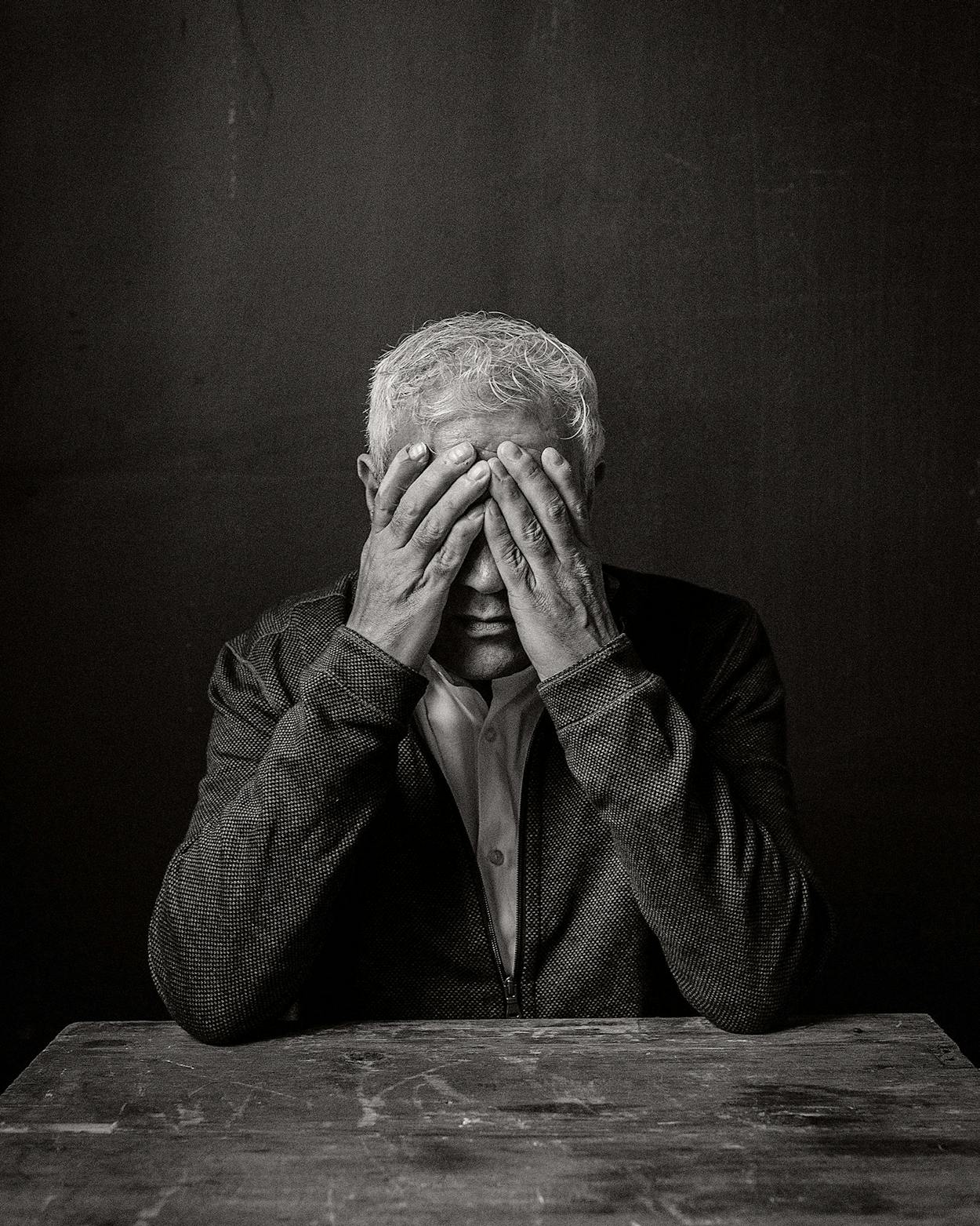

When the jury announced its guilty verdict, Cook hung his head, placed his hands over his eyes, and wept. At the punishment phase, the state called psychologist Landrum, who testified that Cook was a “severe” psychopath and a deviant pansexual. A psychiatrist declared him an “extremely severe” threat to others. He was sentenced to death.

Before being taken away, Cook spoke to the Courier-Times, claiming that he was innocent and had been framed. “One day I’ll prove I didn’t do it,” he swore. “If it takes me ten years or twenty years, I’ll prove I didn’t do it.”

Just two months later, Jackson, the jailhouse informant, recanted his testimony. The career criminal had been released from prison, and on September 12, he gave an interview to a reporter from the Dallas Morning News. His murder charge had been reduced to involuntary manslaughter, said Jackson, after he made a deal with prosecutors to testify against Cook; he’d been released eight days later. But, he continued, Cook had never actually talked to him about the murder. Rather, it was law enforcement officials who had, showing him crime-scene photos and asking questions loaded with details. The Morning News reporter, a man named Donnis Baggett, began digging into the story. “I was doing a lot of criminal justice stories out of that area,” Baggett later recalled, “and there were already a lot of questions about the Cook case.”

And not just Cook’s. “There was suspicion about the way cases were being handled in Smith County,” Baggett continued. The county’s aggressive prosecutors and conservative juries were known for handing out harsh sentences. “The DA’s office was modeled on the Henry Wade theory of prosecution,” recalled longtime Tyler lawyer Bobby Mims, referring to the legendary law-and-order Dallas prosecutor from the sixties. “If an officer brought a case, the DA was going to prosecute, unless there was a plea. You won and let the appellate courts sort it out.” Tyler also had serious problems with some of its police officers. In the year after Cook’s trial, two undercover agents with the Tyler Police Department began doctoring reports and planting drugs on local residents, staging the biggest drug bust in East Texas history. (The resulting scandal led to the indictment of the two agents; one of them, Kim Wozencraft, later wrote the novel Rush about her experience.)

It took Baggett nine months to check out the informant’s claims to his satisfaction and put together an in-depth story about Cook’s case. “Ex-inmate says his lie put man on death row,” read the explosive Dallas Morning News front page on June 15, 1979. In the story, district attorney Clark denied any deal and blamed prosecutor Thompson, who could not speak for himself because he had committed suicide the previous October (friends and family insisted it had nothing to do with Cook’s case). The same day that Baggett’s story ran, the Longview Daily News featured an article on Cook that questioned his alleged propensity for violence. A reporter had looked into the doctors’ reports at Rusk; yes, Cook could be hell on cars and windows, but he wasn’t violent with people.

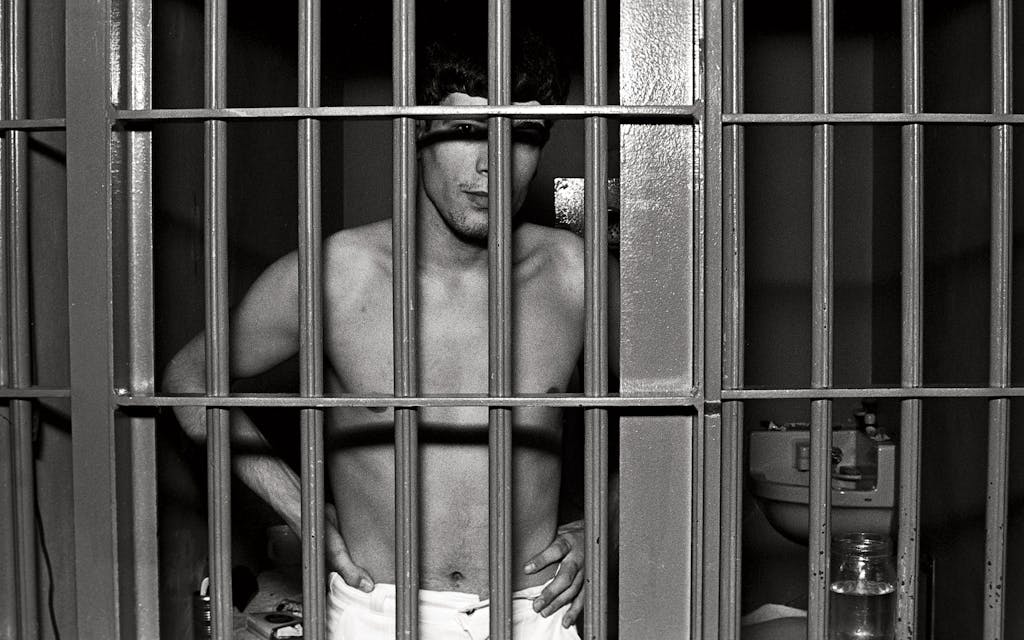

In response, a lawyer in Longview named Harry R. Heard offered to help Cook appeal his conviction. His offer brought some relief to the inmate, who by this time had become an easy mark in prison; he would later report that within days of arriving on death row in Huntsville he’d been thrown against a wall and raped by three inmates, one of whom carved the word “pussy” into his buttocks with a makeshift knife, rubbing in dirt to create a tattoo. Cook became a “punk,” forced to service other inmates, and was made to shave his legs and wear makeup made with Kool-Aid powder.

Cook refused to tell on anyone—snitches got stitches—and turned to writing as he waited on his appeal. On a blue Royal typewriter he bought with money from a sympathetic minister, he composed letters declaring his innocence, sending them to 60 Minutes, 20/20, and Geraldo. When a guard gave him a pocket dictionary, the high school dropout read it to build his vocabulary. As months turned to years, he also checked out law books, learning enough to help other inmates with their writs. It was a way to fight against the gloom and abuse, though sometimes, overwhelmed, he would cut himself with a razor on different parts of his body, just to feel something besides desperation—or to get himself moved to the infirmary or another cell.

It would take almost a decade for the Court of Criminal Appeals (CCA) to finally rule on his case, in December 1987: his conviction stood. Two and a half weeks later, Cook received news from his father that his brother had been shot to death outside a Longview pool hall. It was more than Cook could bear. After a particularly brutal rape, Cook tried to kill himself with a homemade razor.

He was taken to the Ellis II psychiatric ward, also in Huntsville, and got a new attorney, Scott Howe. He also got an execution date: July 8, 1988. Howe filed an appeal with the U.S. Supreme Court, which granted Cook a stay and sent the case back to the CCA. But the lower court once again approved the execution. After another rape and a humiliating strip search in front of fellow inmates, Cook set out to kill himself once more. After writing a note—“I really was an innocent man,” it read—he cut his arm, leg, and throat, then sliced his penis, almost severing it.

He was saved by doctors, who reattached his penis. And in September 1991, for the first time in his life, Cook got the better of Smith County when the CCA, in a rare move, reversed course, throwing out his conviction and sentence on a technicality: the psychiatrist who had interviewed Cook and testified that he was an “extremely severe” threat to others had never read him his rights. Howe felt confident Cook’s exoneration was inevitable, telling a reporter, “Every piece of evidence that the prosecution used to convict Kerry of this crime can be undermined, proven to be false, or explained.”

One of the letters Cook sent out during his time on death row was a 61-page handwritten plea to Jim McCloskey, the founder of a nonprofit known as Centurion Ministries. The organization, based in New Jersey, was devoted to freeing the wrongly convicted and had already helped exonerate nine inmates, including Texas prisoner Clarence Brandley. McCloskey, a burly former divinity student, had been struck by the length and tone of the letter, in which Cook laid out his case and the details of his life—the drugs and alcohol, the foolish teenage escapades, his strained relationship with his parents. He’d done a lot of stupid things, Cook swore, but he hadn’t killed Edwards. “He was very open and honest about his personal history,” said McCloskey. “It was so earnest.”

McCloskey decided to visit Tyler in August 1990. He had read the trial transcripts, but he’d also learned many details of Cook’s ordeal from a series of articles in the Dallas Morning News by David Hanners, a reporter who had looked into why the CCA had taken more than eight years to rule on Cook’s case, longer than any other death row appeal in American history. The more Hanners investigated, the more skeptical he’d become of Cook’s guilt. In his first article, in February 1988, he’d poked holes in the state’s entire case, noting everything from dubious police work and forensics to “overzealous” prosecution.

Hanners discovered that investigators had never sent Edwards’s clothing to a lab for testing. They had also failed to find one of the murder weapons, a bloody fourteen-inch knife. (It was discovered in a closet a few feet from Edwards’s body five days after the murder, by the father of Paula Rudolph, Edwards’s roommate). Hanners spoke with an FBI expert who said there was “no way” a fingerprint could be aged, and the journalist saved particular skepticism for how Rudolph’s identification of the man she’d seen changed over time. In other stories, the reporter highlighted the problematic nature of Landrum’s involvement. The psychologist, it turned out, had worked at Rusk and examined Cook as a teen in 1973 and 1976. His findings back then: Cook was “without psychosis.” His prognosis: “Good.” Yet when Landrum testified in 1978, wrote Hanners, he’d said that Cook was “a sociopathic, drug-abusing sexual deviate who couldn’t be rehabilitated.”

The articles, the transcripts, and Cook’s own words filled McCloskey with questions. As he drove the pleasant streets of Tyler, past the extravagant displays of roses, he focused on one enigma in particular: Why had police so quickly abandoned Mayfield as a suspect? The description of the mysterious man had seemingly matched him best; Mayfield’s relationship with Edwards, whom he’d met working at the library, had been torrid. Just a month before the murder, Mayfield had left his wife for the younger woman, moving into an apartment with her, also in the Embarcadero. But when he returned to his wife just four days later, Edwards attempted suicide, creating a campus-wide scandal that led to Mayfield’s dismissal from his job.

The police had never searched Mayfield’s seven cars, his home, or the apartment he kept with Edwards, even though a new tenant hadn’t moved in. They also had never questioned Elfriede and didn’t interview anyone on Mayfield’s staff at the library. When the police asked for polygraphs for Mayfield and his daughter, the request had been blocked by Mayfield’s lawyer, Buck Files, who told investigators that his client had passed a private polygraph. And the police had appeared to ignore other promising leads, such as one from a friend and colleague of Mayfield’s, psychology professor Frederick Mears, an expert in polygraphs who called the police department a few days after the murder. As Mears would later testify, he told an officer that Mayfield had asked for “assistance in taking a polygraph test” but the police had never followed up. (Mayfield insisted in a deposition that he had asked only “how a polygraph worked.”)

McCloskey set out to do what the police had not: he began interviewing Mayfield’s friends, neighbors, relatives, and colleagues one-on-one. He was astonished by what he learned. “I kept hearing, ‘It’s about time somebody asked me these questions,’ ” McCloskey said. He spoke with more than fifty people, some of whom gave him affidavits. Mayfield was known to be carrying on at least one other affair in addition to his relationship with Edwards, and, according to one acquaintance, he had a “terrible temper.” Another person asserted that Mayfield was a “vindictive person.” A third stated, “We at the library were all afraid after the murder because we suspected Mayfield of killing Linda.” (Mayfield would later contest this unpleasant portrait, testifying that “Centurion Ministries came up with a lot of stuff [that] was not true.”)

McCloskey also learned that Edwards, according to a library secretary, “totally worshipped” Mayfield and was possibly stalking him. Another co-worker said that, during the short period after Mayfield returned to his wife, Edwards had declared two or three times, “I am going to get him back, no matter what.” McCloskey found witnesses who said that, after losing his job, Mayfield had planned to move to Houston and was worried Edwards would follow him. The day of her murder she had surprised him in person three times—including in the evening at his home, where she spoke with both Mayfield and his wife just hours before she was killed.

In a chilling twist, psychology professor Mears told McCloskey—as he’d told police in 1977—about a disturbing book he’d found in the library called The Sexual Criminal: A Psychoanalytic Study, which contained graphic photos of female victims of brutal mutilation murders. Mears swore in an affidavit that “I learned from the staff in the library that this book had been ordered personally by James Mayfield.” What struck McCloskey was that the vicious injuries suffered by several victims in the photos—to the neck, back, and mouth—were akin to those inflicted on Edwards. One of the victims had had her vagina “dissected”; another had been left to lie in a position similar to Edwards’s. Mayfield denied ordering the book, and would later assert in court that he had never even seen it. But McCloskey couldn’t help wondering. Had Mayfield used the book as a primer?

McCloskey was uncovering so many new facts that he decided to write a report, which he gave a no-nonsense title: “Why Centurion Ministries Believes James Mayfield Killed Linda Jo Edwards.” With Cook’s retrial looming, McCloskey persuaded Paul Nugent, a young, scrappy lawyer in Houston who had helped exonerate Clarence Brandley, to take the case. Nugent would face off against Smith County’s current district attorney, a former municipal judge named Jack Skeen who also happened to be a cousin of A. D. Clark III’s, the DA who had overseen the first trial. Skeen had come into office in 1983 promising to clean up the mess from the drug-bust scandal and to be tough on criminals. “Jack Skeen was tenacious,” recalled Robert Perkins, who worked under him. “He was never afraid to try difficult cases, and because this murder was such a high-profile and vicious one, it was not one he’d let go of.”

The case would be mostly handled by Skeen’s top assistant, David Dobbs, a smart and personable lawyer who had been in high school when Edwards was murdered. Before Nugent signed on, Dobbs met with McCloskey and assured him that the prosecutorial issues in Cook’s case were in the past; if he and Skeen felt that Cook hadn’t committed the murder, they’d dismiss the charges. McCloskey liked the fresh-faced lawyer and was so encouraged that he gave Dobbs a copy of his report. Dobbs reciprocated by sharing valuable documents, such as police statements and transcripts of grand jury testimony in 1977 that had never been shown to Cook’s defense lawyers before being sealed by the trial judge.

McCloskey focused on one enigma in particular. Why had police so quickly abandoned Mayfield as a suspect?

Reading through the material, Nugent and McCloskey were amazed. Taylor’s two nephews and Hoehn had testified to the grand jury that, a few days before the murder, Cook had shown them hickies on his neck, saying he’d gotten them from a woman he’d met at the pool; she invited him to her apartment, he’d said, where they’d necked on the couch. One of the boys testified that Cook had said her name was Linda or Limma, and Hoehn said that she was the same woman in whose window he’d peeped. Hoehn had also told the grand jury that Cook “wasn’t paying any attention” to the movie on TV.

The documents not only gave a plausible explanation for how Cook’s fingerprint had gotten on the patio door, they undercut the prosecution’s theory of a crazed stranger butchering a pretty woman in an unfulfilled gay frenzy inspired by an art film. The only problem: Cook had always insisted he’d never been in the apartment. At McCloskey’s next visit, the inmate confessed that he had lied about how the fingerprint got on the patio door. He had, in fact, met Edwards at the pool three days before her murder, he said, and she had invited him to her apartment, where the two shared iced tea and kissed on the couch. After Cook was arrested, his father had made him promise to never reveal this because the police would surely nail him for the murder.

The explanation struck McCloskey and Nugent as plausible. Dobbs, however, was skeptical. He had already interviewed Mayfield and found him an unlikely butcher. “He didn’t seem like a killer,” he said. “He loved her. He’d cry when he talked about her.” Dobbs found it hard to believe that Edwards would have been interested in a weirdo like Cook; besides, she was hung up on Mayfield. It seemed more likely that Cook had gotten the hickies from a man, and that the story about his father was a lie. Why keep quiet about such a possible lifesaving truth for fifteen years?

In fact, according to Dobbs, there was a better explanation. The previous investigators and prosecutors had always suspected Cook had an accomplice; the damage to Edwards’s body was more than one person could have reasonably done in fifteen minutes. That accomplice, the first prosecutors figured, was Hoehn, whose short blond hair could have appeared silver from a distance. But they “didn’t have anything to put a handle on that we could prosecute,” as assistant DA Dunn told the Dallas Morning News in 1988, so they’d given Hoehn immunity and asked him to testify. The prosecutors told Dobbs (and later a grand jury) that, during Cook’s trial, the defense had proposed a deal: drop the death penalty and Cook would testify against Hoehn, the actual killer, in whose yard Edwards’s body parts were buried. When the police didn’t find anything in the yard, the discussion had ended. (Ament admits there was a discussion but insists that he and Dixon were merely feeling out the prosecution on a deal to avoid the death penalty. “Kerry never confessed, I guarantee you that.”)

Dobbs shared Smith County’s theory with McCloskey one evening while the two were standing in Edwards’s vacant apartment, where they had gone together to try and figure out what the roommate had seen. According to McCloskey, Dobbs said, “It wasn’t Kerry that Paula saw. It was Robert Hoehn. I think Kerry was in the closet dropping the knife.” McCloskey was baffled. Though he was glad to be collaborating with Dobbs, he found the hypothesis strange; after all, there was no physical evidence to connect the mild-mannered hairdresser to the crime.

McCloskey grew even more wary of Dobbs a few months later, when Cook was bench-warranted back to Smith County in advance of the retrial. Unannounced, the prosecutor showed up at the county jail to introduce himself without Nugent present, a potential violation of state bar rules. According to Cook, who called journalist Hanners afterward, Dobbs asked about the fingerprint—the only evidence connecting Cook to the case—and suggested a polygraph. Dobbs denied this. “I understand ethics and I didn’t violate any ethics,” he told Hanners for a story that ran three days later.

For McCloskey, the maneuver was an omen of sorts: it indicated just how hard, and possibly how dirty, Dobbs was willing to play in order to win. (The trial judge later called the meeting “improper” and a “breach of duty and protocol” but said it did not rise to the level of prosecutorial misconduct.) Hanners’s stories—the journalist would eventually write more than fifty, repeatedly questioning the validity of the conviction and the integrity of Smith County law enforcement—were only raising the stakes. The desire to prosecute Cook in the face of so many questions, thought McCloskey, was a matter of stubbornness. Only pride could explain why Dobbs and Skeen were taking Cook to trial again, fifteen years after the murder.

For Dobbs it was much simpler. Cook was guilty, and he was going to send him back to death row, where he belonged.

The second trial opened in November 1992 at the Williamson County courthouse, two hundred miles away, in Georgetown, where the case had been moved because of its notoriety in Tyler. As Cook entered the courtroom with Nugent and McCloskey, his hair already graying at age 36, he felt hopeful. But his team was frustrated almost at the outset, when the judge announced a series of decisions in the state’s favor, including that he would not allow any witnesses to testify about Cook’s conversations with them in 1977 regarding the hickies from Edwards in her apartment. (The judge determined it to be rank hearsay.)

Taking advantage of the ruling, Dobbs and Skeen insisted that Cook was a total stranger to Edwards, with only one reason to be in the apartment: to kill and mutilate her, inspired by the movie scene. The state called familiar witnesses—Edwards’s roommate identified Cook from the stand once again—as well as a new one: former reserve deputy Robert Wickham, who testified that, during jury selection for the first trial, he had taken Cook in the courthouse elevator from the basement to the second floor. In those seventeen seconds, Wickham testified, the two had had a conversation, and the inmate confided, “I killed her and I don’t give a shit what they do to me.” Wickham had never told his superiors because, “I thought it was just going to be his word against my word.”

Exasperated, Nugent tried to undercut Wickham’s credibility and highlight the incompetence of the investigation, from the failure to test Edwards’s clothes to the dubious science of fingerprint dating. He focused on Mayfield and his daughter as likelier suspects. One police report, originally hidden from the defense, revealed especially bizarre behavior from Luella. In addition to making death threats against Edwards, she had dressed up in her cadet uniform from Police Explorers, a youth organization, and visited the Embarcadero. While there, she had pretended to be a cop investigating Edwards’s murder—she told residents the crime somehow involved Mayfield—two weeks before the actual murder. (On the stand, Luella said she had no memory of the incident.)

At closing arguments, both Dobbs and Skeen spoke at length about the nylon stocking; in one scene in the film, a boy caressed one, and, of course, Edwards was missing one. This stocking, they emphasized, was key to understanding Cook’s perversion. “It does not make any sense,” urged Dobbs, “unless you take a look at the facts of this case and see what is missing from Linda Jo Edwards’s mutilated body. Interesting, isn’t it?”

Even more interesting was when jurors, deliberating in the jury room, asked to examine the evidence and broke open an evidence bag. When they unfurled Edwards’s jeans, out fell a stocking—the very one that two sets of prosecutors had long insisted Cook used to carry away body parts. “If I were Smith County,” McCloskey told the Morning News the next day, “if I were Tyler police, I’d be absolutely humiliated.”

After five days of deliberating, with the jury deadlocked six to six, the judge declared a mistrial. Again, Cook wept. He had finally beaten back Smith County—if only to a draw. Almost immediately, Skeen and Dobbs announced they would prosecute him again. Cook, meanwhile, told a reporter he’d keep fighting: “I will never give up until I’m vindicated.”

He was found guilty again fourteen months later. The third trial, also in Georgetown, largely mirrored the previous one, though now, because of modern technology, experts had identified five fingerprints belonging to Cook on the patio door. Once again, Cook’s lawyers were not allowed to bring in any testimony about Cook’s being inside the apartment. During the punishment phase, Dobbs pushed to send him back to death row, portraying Cook as a teenage predator who had grown more depraved on death row. Skeptical of Cook’s claims of prison rape, Dobbs suggested in his questions to defense experts that the inmate had voluntarily had the “pussy” tattoo inscribed and that his gay dalliances before prison made his supposed assaults less traumatic.

Dobbs also showed a graphic prison video of Cook’s last suicide attempt, a fifty-minute recording that depicted Cook naked on the blood-soaked floor. Cook’s self-mutilations, declared Dobbs, were a sign he was a danger to society—a claim supported by Landrum, who took the stand once more to testify that there were studies, including one out of Rusk, to prove this. “Very violent, aggressive people sometimes are suicidal and self-mutilate,” said Landrum, “especially if there is no other victim available.” Though Nugent insisted that Cook’s actions on death row came from desperation, not deviancy (“Yes, Mr. Cook is a danger. He is a danger to himself”), his efforts did no good. Cook was handed a second death sentence.

Nugent filed a 213-page appeal, with 55 points of error, summarizing for the first time the misconduct and mistakes in the case. In detail, Nugent described the prosecution’s ongoing attempts, from 1977 to 1992, not just to try Cook but also assassinate his character. “In every step from the grand jury room to the Supreme Court,” he wrote, “the State has humiliated the appellant with accusations of singularly perverse acts of violence, with graphic descriptions of homosexual activities thrown in for good measure.”

This time, the work paid off. In November 1996 the CCA threw out the verdict, decrying the state’s role in the case with unusually harsh language, proclaiming that “prosecutorial and police misconduct has tainted this entire matter from the outset.” Though most of the misconduct singled out was from the first trial, the court noted other disquieting behavior from the second and third, including Dobbs’s visit to Cook at the jail. In a concurring opinion, a judge found the misconduct so bad that he thought a fair trial was no longer possible and that in his view Smith County should not be allowed to continue prosecuting Cook: “The State with all its resources and power should not be allowed to make repeated attempts to convict an individual for an alleged offense.”

For the first time, a judge allowed Cook to post bail, and almost exactly a year after the CCA’s decision, the inmate walked out of the Smith County jail. His father had died of cancer while he was on death row, but he was met by his mother, who wept as she hugged her son. Cook looked exhausted—he hadn’t slept in days—and the two held their embrace for an extended period, surrounded by reporters, including a film crew from ABC’s news program Turning Point. “I’m home, Mama,” he said.

There was little remaining evidence against Cook—the fingerprints, the changing memory of the roommate, the belated words of the reserve deputy—but many in Smith County, especially those in law enforcement, still found it difficult to believe in his innocence. Cook’s proclivities were too aberrant, his troubles in prison too disturbing. “Everyone around here thought he was guilty,” recalled one woman who worked at a law office across the street from the courthouse. “They all said really crude and ugly things about Kerry.”

A week after Cook’s release, a fax showed up in a communal space shared by her law office and three other firms. It had been sent by one former assistant DA to another, and it contained lyrics to a “Kerry Max Song” to be sung to the tune of Steve Miller’s “Take the Money and Run.” The sender, Lance Larison, had created three verses (“If we had justice Cook’d be dead today”), a chorus (“Go on, cut my penis for fun”), and a caricature of Cook holding a chain saw and saying, “Now I’m out, this should make a much smoother cut.” The message was clear: Cook was a twisted criminal who had gamed the system. “Spent twenty years avoiding justice,” went one line, “despite the fact the guilt is all his.” The fax was laid on a couch in the communal area. “Everyone thought it was real funny,” said the woman. “They talked about the tattoo as if Kerry had it put there himself.”

This perception of Cook in Smith County was made worse by the fact that he was gaining more allies in the outside world. His case had been drawing increased national attention, especially after Dobbs and Skeen announced that they intended to try him the following September for an unprecedented fourth time. (“We wouldn’t even consider a plea to life,” declared Dobbs.) After his release, Cook had moved to Dallas, where he worked as a paralegal and began speaking publicly about his case, lecturing to a Texas government class at Brookhaven College, in Farmers Branch, and at fundraisers for Centurion Ministries and the Innocence Project. He ventured to Yale, Princeton, and Columbia to deliver speeches about his experience, sometimes accompanied by his new girlfriend, Sandy Pressey, whom he’d met at an Amnesty International meeting. On their first date, they’d gone to see Titanic, and Pressey had held Cook’s hand through the entire film.

Cook also visited a deep-trauma expert named Rycke Marshall, the former chief psychologist at Terrell State Hospital. Cook was the most broken person she had ever seen. “He had severe post-traumatic stress disorder,” she recalled later. “He’d been emasculated by the rapes and was actively suicidal.” Marshall was shocked by all the times Cook had cut himself, but she was even more shocked by the notion advanced at trial that self-mutilation was an act of violence. “Self-mutilation is a very primitive behavior designed to alleviate overwhelming stress,” she said. “The physical pain is a way of trying to focus and pull yourself together.” Cook’s counselor at Ellis II had found him to be sincerely suicidal, noting in particular the abuse that the tattoo carved into his buttocks invited, and Marshall agreed. Cook, she decided, had severed his penis not out of savagery but despair. “He was saying, ‘I don’t need it anymore,’ ” she said. “It had nothing to do with the murder and everything to do with how dehumanized, helpless, and emasculated he felt.” (Rusk has no record of the self-mutilation study Landrum testified about.)

To prepare for trial once again, Nugent received the help of two new lawyers, both funded by Centurion Ministries: Cheryl Wattley and Steven “Rocket” Rosen. In February 1999, as the lawyers readied themselves for trial, Wattley received a call from Dobbs with remarkable news: a semen stain had been discovered on Edwards’s underwear, almost 22 years after her murder. Now that DNA testing was available (the technology had been developed in the eighties), the DA’s office was having the stain tested. In a conversation with journalist Hanners, Dobbs hailed the discovery, declaring that the semen “could only have been left by the killer.”

Cook and Mayfield gave blood samples, and Dobbs filed a motion to delay the trial to finish the testing. But the defense lawyers, who had lined up eight forensic witnesses and figured the DNA results would come in before the end of the trial anyway, pushed to keep the original date. Meanwhile, Dobbs proposed trying to work out a no-contest plea deal, offering first a forty-year sentence, then a deal where the judge could sentence him to less. Cook refused both. Finally, on the morning of jury selection, Dobbs offered a take-it-or-leave-it bargain: plead no contest to murder, get twenty years, and because of time already served, be free—though not exonerated. The judge gave Cook thirty minutes to decide. Terrified of losing again in what he felt was a rigged fight, Cook accepted the deal.

Two months later, the DNA results came back: the semen belonged to Mayfield. Speaking to reporters, Dobbs expressed a new understanding. “It’s irrelevant,” he said, explaining that, according to the lab, it was possible the stain had been left weeks before Edwards’s death. “Cook has been convicted of the murder.”

For Cook, however, this was the most powerful proof yet that he’d had nothing to do with Edwards’s death. Many outside observers agreed. Within a few months, the Dallas Observer published a two-part cover story on his case titled “Innocence Lost.” The next year, in 2000, the Houston Chronicle printed a front-page investigation into the legal workings of Smith County, with quotes from lawyers who accused the DA’s office of railroading defendants and having a “win at all costs” mentality. Cook’s case, wrote reporter Evan Moore, was “one of the better known examples of prosecutorial misconduct in the nation.”

Energized, Cook took his story even farther into the world, delivering speeches on capital punishment and overcoming adversity at events in Paris, London, and Rome. In Strasbourg he led five thousand anti–death penalty protesters through the streets, holding hands with Bianca Jagger. He and Pressey married, and soon had a son, Kerry Justice, whom they called KJ. In 2001 Cook testified before the Texas Legislature in favor of a moratorium on the death penalty; his story also became part of The Exonerated, a play that was made into a movie in 2005 (he was played onstage by Tim Robbins and Richard Dreyfuss, among others; Aidan Quinn played him in the film). He was befriended by the likes of Pete Townshend, Hilary Swank, and Marisa Tomei. Frontline televised a sympathetic story, and photos of Cook—with Susan Sarandon, Morgan Freeman, Robin Williams—appeared in the media. Bruce Springsteen gave him a Jack Russell terrier puppy. Hillary Clinton asked him to help bring the play to Washington, D.C.

Dobbs and Skeen, meanwhile, grew increasingly incensed with their portrayal as unprincipled prosecutors. Cook still had a murder conviction on his record, and in their eyes his fame was an affront to the justice system. They sued the Houston Chronicle for libel over its story on Smith County, a bitter lawsuit that dragged on until 2005, when the state Supreme Court threw it out by unanimous vote. Many of those who had sought to have Cook executed had since moved into other positions—Skeen was now a district judge, assistant DA Dunn was a county judge, and Dobbs had gone into private practice with his wife, a lawyer who helped him prosecute Cook in 1992—and Cook’s ongoing celebrity was an insult to their careers. The DNA proved that Edwards had had a relationship with Mayfield, not that Cook was innocent. As far as they were concerned, Cook was not only not exonerated, he was also clearly unstable.

In fact, Cook was showing signs of volatility. He’d begun writing a book about his life, consulting with former Tyler undercover cop Kim Wozencraft, but their work was often made difficult by his erratic behavior and PTSD. “He would start writing, then go off on a rant,” she would later recall. “His words seemed paranoid, but I realized I don’t know how you could even define ‘paranoid’ for Kerry.” In 2007, when Chasing Justice finally came out—a detailed account of everything from Cook’s arrest to his decision to take the no-contest deal—it got rave reviews. (“If it were fiction,” wrote John Grisham, “no one would believe it.”) But the reviews and adulation only served to deepen Cook’s rage over his incarceration. After so many years in despair and isolation, he found an outlet on a new platform: Facebook. Posting letters, poems, and songs from supporters (one young musician in Dublin wrote him a song titled “Don’t Quit”; a Danish band came up with an homage called “Kerry Max Cook”), he also wrote frequently, in pitched tones, about being wronged. His case, he wrote, “is known as the worst documented example of prosecutorial misconduct in Texas history.”

Though he was traveling the world, from Ireland to Dubai, and delivering speeches about never giving up—youth groups frequently gave him standing ovations—in Texas, Cook was still a killer. With the murder conviction on his record, Cook had trouble finding a job or signing a lease. Several times he had to move his family after neighbors in Dallas found out about his past (one woman threatened to plaster the neighborhood with signs saying “Convicted Murderer Lives Here”). He had been acquitted in the eyes of the public, but that was not enough. What Cook really wanted was to be exonerated in the eyes of the law.

I first met Cook in 2012, when I was working on a story for Texas Monthly and the New York Times. I spent a day with him in his North Dallas neighborhood, following along when he went to pick up KJ, then eleven years old, from school. When we arrived at the campus, classes had just let out, and several kids squealed and ran toward Cook when they saw him. One little girl squirmed away from her mother. “Mr. Kerry!” she yelled, laughing, and then jumped into his arms. “Haleigh!” he responded, tickling her. When I asked the school’s director about Cook, she said, “We know him. We know what kind of man he is.”

Cook was fast-talking and neurotic, returning again and again to the same subject: his wrongful conviction. He still suffered from PTSD and depression, he told me, and repeated himself with the same well-worn phrases, often hyping his case as the worst of all time. But he was also sweet, funny, and charming, often looking to Pressey for help finishing his sentences. He was excited because his case had come to the attention of the Innocence Project, a national nonprofit that had, with the help of DNA testing, successfully secured the exonerations of more than three hundred people. In February, Gary Udashen, from the Innocence Project of Texas, had filed a motion for DNA testing on the other crime scene evidence in Cook’s case, including the bloody knife and a bloody hair found on Edwards’s body that investigators had long ago determined belonged to neither her nor Cook.

If the testing showed no evidence of Cook’s presence at the crime scene, and if someone’s else’s DNA showed up in the hair, Udashen believed there was a chance the courts might finally exonerate him. The idea made Cook practically giddy, and he compared his plight to that of two other men who had recently been exonerated after wrongful murder convictions: Anthony Graves, released in 2010, and Michael Morton, released in 2011. The prosecutors in both cases were facing disciplinary action—Graves’s prosecutor would be disbarred in 2015, and Morton’s prosecutor would serve jail time in 2013—and Cook was beginning to feel hopeful that he might get similar justice.

But when the DNA motion was approved, and officials began looking for crime scene evidence, they discovered that law enforcement had destroyed the hair in December 2001. It was a huge blow, but not a fatal one, as the other results revealed exactly what Udashen had hoped: none of Cook’s DNA could be found on anything. The DNA on Edwards’s underwear was still conclusively Mayfield’s.

Udashen and Nina Morrison, a lawyer with the Innocence Project, filed a writ of habeas corpus in September 2015, asking for Cook’s conviction to be thrown out based on the DNA evidence. The lawyers also claimed that Dobbs and Skeen had known in advance the results of the 1999 DNA testing and that they’d had something to do with destroying the hair—only eight months after Texas had passed a new law granting post-conviction DNA testing and barring the destruction of biological evidence without notifying the defendant. (The state denied any foreknowledge or that there was any misconduct, noting that by December 2001 Cook hadn’t filed any challenge to his conviction and thus “thirty-four months after his conviction, the State disposed of some of the evidence from the prosecution in the ordinary course of business.”) After filing another motion to recuse the judge who would oversee the writ (the judge’s late husband was the lawyer who’d received the fax of the “Kerry Max Song”), Cook’s lawyers filed an additional one, this time asking the DA’s office to provide any exculpatory evidence it hadn’t before.

The Smith County DA by this time was Matt Bingham, a law-and-order prosecutor who had served as assistant district attorney under both Skeen and Dobbs. Bingham, elected in 2004, had never worked on Cook’s case, and he invited Udashen and his law partner Bruce Anton to look through the entire case file of 49 boxes. The two discovered evidence that Cook’s earlier defense lawyers said they had never seen, including a 1991 police report stating that Edwards’s roommate had told prosecutor Thompson that it was Mayfield, not Cook, she had seen in the room. (The state insisted the detective had made a mistake and transposed the names, a fact the detective himself affirmed in a later affidavit. As to why the defense never saw the original report, Dobbs insisted he shared it with Rosen in 1999.) Wanting to question Mayfield, Udashen and Morrison pestered Bingham. To their surprise, the DA, who had never spoken with Mayfield either, suggested they go see him together.

In April 2016, Udashen, Bingham, and several other lawyers traveled to see Mayfield, whom Bingham had offered immunity from prosecution, at his home in Houston. Mayfield and Elfriede, who had baked cookies for the occasion, welcomed them in their living room. The former library director, aging and hard of hearing, repeated many of the things he had said in the past, but then he made a couple of astonishing admissions. First, he said, contrary to his previous denial, he had seen the book The Sexual Criminal before Edwards’s murder, and he and Mears had discussed it. More important, he confessed that he and Edwards had had a sexual rendezvous on the day before her death. This was in direct contradiction to what Mayfield had long maintained—that his affair with Edwards was over three weeks earlier—and suddenly made him a more viable suspect. Armed with the newly discovered police report, Cook’s lawyers could credibly allege that Mayfield had had both the motive and opportunity to kill Edwards: he’d lost almost everything after their affair was revealed, he’d been the last person seen with her, and his DNA had been found on her clothing.

Cook, who by this time had moved his family to New Jersey, could barely contain his excitement at the revelation. The Smith County judge who had been set to rule on the writ recused herself, and the new one—Jack Carter, of Texarkana—soon scheduled a hearing to look into Cook’s claims. Cook would finally get to testify and tell his story, and his lawyers would at last get to question, under oath, the men who had sent him away. “This is the story of my own Tiananmen Square against an army of Smith County tanks,” he emailed me.

Udashen, meanwhile, knew that the battle ahead was not so clear-cut. A veteran of twelve exonerations, he recognized that a complex case like Cook’s was resolved only after considerable give-and-take with the state. He cautioned Cook to focus on his exoneration, not on his quest to punish the prosecutors. First, Cook needed to be found actually innocent; then he could seek for a court of inquiry or the state bar to look into the conduct of his adversaries. Cook complained heatedly—how could he possibly let Smith County off the hook?—but eventually relented, signing an agreement in which he stated that his goal was exoneration and nothing else, including “conducting a public hearing.” He also agreed to stop posting his abusive opinions of Smith County on Facebook.

Udashen had already been talking to Bingham about working toward a deal. In addition, he reached out to Dobbs, who, over the next few months, helped lay the groundwork for various plea offerings from the DA’s office, all of which Cook turned down. (Udashen, knowing Cook’s feelings toward Dobbs, downplayed his role.) Dobbs insisted to Udashen that he had never known about the DNA results in advance and that he was looking forward to testifying. (“Clearing things up would be a blessing,” he said.) On June 5, 2016, the day before the hearing, Bingham, Dobbs, and Udashen met at a Mexican restaurant in Tyler, where Bingham made his best offer yet: the state would agree to set aside the conviction based on the new evidence of Mayfield’s lie about his final encounter with Edwards, but only if the defense agreed to throw out its other claims, including those alleging prosecutorial misconduct. Both sides would leave for the judge the final claim of actual innocence. There would be no testimony from Cook, Dobbs, Skeen, or Mayfield.

Udashen and Morrison were ecstatic. Here, at last, Cook’s exoneration was within reach; it would become official as soon as the CCA ratified the deal. But when they informed Cook of the arrangement a few hours later, their client was furious—especially once he learned that Dobbs and Skeen would not be required to testify. Cook grew so agitated he threatened to go home to New Jersey. In his mind, the Smith County DA’s office had won over and over for 39 years, and now it was winning again.

No, insisted Udashen and Morrison, he had won. It was exactly what Cook had yearned for: exoneration. They would still have to fight for actual innocence, but he was truly free—no more murder conviction. To turn the deal down, Udashen cautioned, was crazy. It would be the biggest mistake of Cook’s life.

Finally, Cook relaxed. He agreed to the deal, and the following morning, after the hearing wrapped, he seemed to have fully come around. He even managed to crack a few jokes at the lunch afterward. McCloskey, who declared the day one of the best in his 36 years of innocence work, grabbed his old friend by the shoulders. “This is a great accomplishment,” he said. “Yes, Dobbs and Skeen skated, but you’ve got to give something to get something.” Cook looked at Udashen across the large restaurant table and said, so that everyone could hear, “Gary, thank you for not listening to me last night.”

The following day, Cook posted the words he’d long waited to say. “I’m free,” he wrote. “I’m free at last.”

Exonerations are deeply compelling. When someone we thought guilty is found to be, in fact, innocent, we seek for ways to make things right—with admiring headlines, with soul-searching articles, with compensation. In this rush to make amends, there is also an expectation. Though we can barely fathom the suffering of someone who has endured such injustice, we look to find in him signs of resilience and magnanimity, of the strength of the human spirit. We want exonerees to be like the Tim Robbins character in The Shawshank Redemption: a model of righteousness, an exemplary man whose calm demeanor and determination underscores just how badly he was wronged, and how right it is for him to go free.

The reality, of course, is much darker. An exoneree has brutal memories to recover from, both physical and psychological, and faces the devastating burden of making sense of his lost years, his ruined relationships, his powerlessness, and his anger. There are a few who are able to navigate this challenge, whose names we remember as a result. Michael Morton spent 25 years in prison, yet in public he speaks of forgiveness for his tormentors. Anthony Graves languished behind bars for almost two decades, yet he spent a portion of his compensation money to set up the Anthony Graves Foundation, which looks into innocence claims from other inmates. Both men were able not only to accept the terms of their release but also to control their demons.

Cook could do neither. The morning after the hearing, he began to fret again, increasingly certain that his lawyers had colluded with Bingham to protect Skeen and Dobbs, who Cook felt was still pulling the strings behind his persecution. Though his friends argued to the contrary—you won, they insisted—he would hear none of it. A day later, he sent an email to his lawyers, which he then posted on Facebook. He’d been humiliated, he wrote, by Udashen’s praise for Bingham and the DA’s office. He could no longer trust Udashen or Morrison, and they were both fired. He continued ranting in subsequent Facebook posts: Udashen and Morrison had not been prepared, he claimed, and had coerced him into the agreement.

Cook had refrained from posting about his case for a month, and now he couldn’t stop, as if a dam had broken, and 39 years of hurt and rage were pouring out. “Again, the Texas legal system has let me down,” he wrote, “leaving me broke and penniless on the goal line of ‘Actual Innocence,’ unrepresented by counsel because I stood up to the system again.” He was grandiose one minute, quoting Franklin D. Roosevelt (“Far greater is it to dare mighty things . . . ”), and self-pitying the next (“Please, please help me someone, anywhere. Please. I cannot give up. I can’t. Please”).

Five days after his exoneration, Cook posted the craziest thing of all: he needed an attorney to throw out the agreement and give him back his wrongful conviction. “I’d rather be convicted again than live with this lie,” he wrote. His friends thought he’d lost his mind, or at least his grasp of reality. “His obsessive contempt for Skeen and Dobbs has clouded his mind,” McCloskey told me. “I think they did him wrong, no question. But to get the DA’s office to toss the conviction was a major accomplishment.”

In fact, Cook was running the risk of putting his actual innocence—and his compensation—in jeopardy. Firing his lawyers and then haranguing Bingham and Smith County made him appear ungrateful and unhinged in a way that could displease the judge. It had certainly dashed all possibility of any further deal with Bingham. On June 15, Cook posted that he had come to his senses. “I do not wish to withdraw the Agreement,” he wrote. “I was upset, felt betrayed.” He apologized to Udashen and Morrison and asked them to take him back. But the lawyers declined, explaining that Cook’s actions had destroyed their credibility as effective advocates.

The actual innocence hearing took place on July 1. Cook, who had worn black to every public event since being freed in 1997, showed up at the Tyler courthouse wearing a light-blue shirt with a tie and a blue jacket. By this time Kim Kardashian had tweeted about his case to her 46 million followers (“You should google Kerry Max Cook his story is fascinating and heartbreaking”), and Cook had found a new lawyer, Mark Bennett, from Houston. Bennett, who’d had a mere twelve days to learn the details of a 39-year case, faced a difficult task: to show that the new evidence was “clear and convincing” enough that, had a reasonable juror known of it back in 1994, he or she would not have found Cook guilty.

Bennett attempted to frame the argument around why Mayfield was the better suspect, but the lawyer representing the state, M. Keith Dollahite, was quick to point out that Mayfield’s admission was not enough to prove that he’d killed Edwards. Nor did the DNA evidence place Mayfield at the crime scene. Instead, Dollahite pointed out, other details were more resonant: that Cook was a convicted felon, that he had spent time at Rusk, that his self-mutilations on death row were evidence of his potential violence. Cook, said Dollahite, trotting out the decades-old arguments, had behaved in keeping with Landrum’s testimony that “very violent aggressive people often are suicidal and self-mutilating, especially when no victims are available.”

Cook leaned forward, holding his head as if he had a splitting headache. On some level, he’d known the state would bring up the same material. And on some level, he knew that Carter would rule against him—which he did, on July 25. “It is this court’s conclusion that a reasonable jury would not necessarily acquit Cook after hearing both new exculpatory evidence and the previous evidence of guilt.” Smith County had won again.

Why did Smith County prosecute Cook in the first place—and then three times more? I asked Dobbs this question on a warm afternoon last October. We were sitting on the outdoor patio at Stanley’s Barbecue, in Tyler, pausing between bites of brisket and sausage. Stirring his iced tea, the lawyer looked up. “He was guilty,” he said. Dobbs has lively green eyes, graying hair, and a genial manner, and though he is wary of reporters, he’d agreed to meet to set the record straight. “The most amazing thing to me is how many people he’s hoodwinked on his path to celebrity. He’s pulled off the biggest fraud of all.”

Dobbs still believed that Hoehn was likely involved. Back in 1992, he’d asked Hoehn’s lawyer if the prosecution was on the wrong path, and, “He said one word: ‘No.’ ” Dobbs pulled out several documents for me to see, including a 2012 affidavit in which the lawyer stated that Hoehn had told him in 1977 that he and Cook sneaked into Edwards’s apartment, where Cook hit her over the head and cut her up—and were then surprised by the roommate.

As for motive, “Who knows?” said Dobbs in his East Texas drawl. “I’ve prosecuted around twenty capital murder cases. You don’t always know. They’d just had sex, Cook was talking about watching Edwards undress. Was Hoehn jealous of his attention to her? I don’t know. Cook showed Hoehn where she lived. They’d been drinking. She wound up dead, and Cook’s fingerprint was found—something he lied about for fifteen years.” To Dobbs, that lie was part of Cook’s pathology as a predator, hustler, and celebrity fraud—a man who blamed the state for his abuse in prison when he was clearly harming himself. “The theory that this arrest led him to being a prison punk is ridiculous,” he said, shaking his head. “That behavior predates this case. He claimed he was raped in prison as a teenager. I don’t want to look like I’m insensitive to abuse in prison—I’m not. But don’t try to attribute every violation to this case.”

Dobbs was still angry that Cook and his defenders were insistent that he and Skeen were the bad guys. “I don’t understand why Kerry thinks I’m a villain. I gave them the police reports and the grand jury testimony twenty-five years ago,” he said. “In 1999 I begged them to delay the trial and wait for the DNA results—then they accused me of knowing the results prior to his plea.” Those in Cook’s camp, he feels, are selective with their memories. “They vilified us in order to block the first retrial,” he said. “They had to. But, Michael, point to something we did that was unfair. We thought he was guilty—I still do. We inherited a mess from the first trial, and we fought hard—for the victim, for law enforcement. But we fought fair.”

It’s a thin line between throwing hard blows and throwing foul ones. When I spoke with Hanners, the Dallas Morning News reporter who spent four years analyzing Cook’s case, he admitted thinking at first that Hoehn was a viable suspect too. But he never found a motive, and after Hoehn died, in 1988, the reporter talked to a close friend of the hairdresser’s, who said that Hoehn had told him that Cook “was never, ever guilty.” Hanners was also suspicious of the 2012 affidavit. “There was nothing to that effect in Hoehn’s statement, grand jury testimony, or trial testimony,” he told me. Cook, who has repeatedly denied a connection to Hoehn beyond that night, showed me a letter Hoehn’s lawyer wrote him in 1988 that directly contradicts the affidavit. “I have followed your case with considerable interest,” the lawyer wrote. “If there was anything that I could do to reverse your sentence and give you a new trial, I would be happy to do so as, in my opinion, you were convicted on considerable put-up testimony and misstatements.”

Photos of Hoehn from 1977 that were given to McCloskey show a man who doesn’t come close to matching the original description of the person in Edwards’s apartment. Hoehn is pale, plainly built, and balding, with blond-brown hair; there is nothing tanned, trim, or silver-haired about him. McCloskey remains astounded by the state’s approach at the second and third trials, considering the prosecution’s belief about Hoehn’s involvement. “Even though Dobbs said he thought Rudolph saw Hoehn,” McCloskey told me, “at both trials he unblinkingly allowed Rudolph to identify Cook as the man she saw. I was flabbergasted.” But, I asked, isn’t that just a matter of a prosecutor doing his job? “To what length do you go to win a case?” replied McCloskey, his voice rising. (Dobbs thinks he might have been less categorical about Hoehn during that evening with McCloskey in Edwards’s apartment, saying something like, “Have you considered that Rudolph might have seen Hoehn?”)

So why continue to prosecute, even as the passing years shed ever more doubt on the available evidence? The answer may have as much to do with the high stakes of the case—Edwards’s murder was the most brutal in Tyler’s history—as the particular character of Smith County. “The more horrific the crime, the greater the need to punish somebody,” a former prosecutor in Dallas and Tarrant counties, Terri Moore, told me. “Once you’ve gone down the road and tried and tried and tried the man, it’s hard to say, ‘We had the wrong man all along.’ ” In Nugent’s eyes, Cook was doomed from the start. “Most wrongful conviction cases come when the authorities choose a defendant and then start investigating the facts, instead of investigating the facts and seeing where they lead you,” he said. “Once Kerry was arrested, the die was cast.”

And because of Tyler’s tight-knit legal community, in which many of the players have a connection to Cook’s case, there are few lawyers without a vested interest in its outcome. “That courthouse is one big family,” noted McCloskey, who has been traveling to Tyler for 26 years now. “They live to protect each other and their reputations and standing in the community. It’s important to maintain the reputation of the DA’s office and not impugn one’s forebears.”

Moore agrees. She became a top assistant for Craig Watkins, the Dallas County DA who in 2007 created the country’s first conviction-integrity unit, which eventually led to 33 exonerations. She credits Watkins’s status as an outsider—he had no connections with former Dallas DAs—for his willingness to scrutinize zealous prosecutions. “It’s easier to investigate a suspicious conviction if it happened under a different administration,” she said. “It’s really difficult if it was you. In Smith County, everyone is connected—Bingham is an extension of Skeen. It takes courage and integrity to do the right thing, and Smith County hasn’t been known for that. Smith County is known for being a locomotive running over everybody.” In the past forty years, there has been 1 exoneration in Smith County, compared to 52 in Dallas County. And it remains a tough place: in 2015, only two defendants were found “not guilty” in the Smith County district courts, which had a 94 percent conviction rate, compared to a statewide average of 83 percent.

Then there’s the particular character of the defendant. Cook, with his public speeches, Facebook rants, and celebrity followers, made it impossible for those in Smith County to walk away. His interviews, the newspaper stories, the attention from Hollywood—these were rebukes too infuriating to ignore, not just because Cook’s behavior maligned Smith County but also because, many of its players felt, it confirmed what they’d said to be true all along. “I have absolutely no doubt Cook was guilty,” Mayfield’s lawyer, Buck Files, told me. When I asked if he would say the same thing if he hadn’t represented Mayfield, he said, “Yes. Cook’s conduct in the pen confirmed what a lot of people thought.” Was he referring to the self-mutilation? “His conduct in the pen, his behavior—words spoken, comments he made to others that showed his involvement in the murder, events that occurred in prison. It may not convince anyone else, but it convinces me.”

Cook’s case remains before the CCA, which must now uphold or deny the judge’s recommendations in favor of his exoneration and against his actual innocence. While most observers believe the CCA will uphold them, in November the court shocked the criminal justice world when it reversed a recommendation in another well-known case and granted actual innocence to four San Antonio women wrongfully accused of rape. Cathy Cochran, a retired CCA judge, hopes her former colleagues will give Cook the same result. “This man may be a petulant, narcissistic publicity hound,” she told me, “but when push comes to shove, he’s right. Is anyone surprised that an innocent man, left to rot in prison for years, told to plead no contest to get out, who wants to be exonerated and take the prosecutors who put him in prison to task, who then has lawyers who know better and who make a deal with the very people he wants to excoriate—is anyone surprised when he finally loses it? He’s reached the end of his rope. But the justice system is required to do justice even to those who are self-destructive.”

I spoke with Cook over the phone in the fall, as he and his wife were getting ready for a trip to Lima, Peru, where he would speak to the local chapter of the Young Presidents’ Organization on “the magic of freedom.” He pinged between various favorite subjects, from his certainty that Smith County would come after him again to his reasons for firing his lawyers, growing more and more emotional as he spoke. Then, pausing for a moment, he asked his wife to leave the room. He had to tell me something about why he’d rejected his exoneration.