For the bulk of the 2,000 years of surf history, water temperatures placed strict limits on where surfers could go and how long they could surf. That meant the sport was largely confined to Hawaii and Polynesia, where it’s warm year-round. But for the past 60 years surfers have been expanding into the farthest and coldest reaches of the globe, due in large part to wetsuit manufacturing pioneer Jack O’Neill, who died in his home in Santa Cruz, California, on Friday at the age of 94.

Born in Denver in 1923 and raised in Southern California and Oregon, O’Neill began bodysurfing in the Pacific as a teenager. After moving to San Francisco in 1949 to pursue a liberal arts degree at San Francisco State, he continued, like others of his ilk, to adhere to established cold-water coping strategies. In the pre-wetsuit age, surfers were still essentially Stone Age technologists. They rode crafts hewn from timber, returned to shore frequently to huddle over driftwood fires, and, when not bare chested, wore wool sweaters into the water for some semblance of warmth.

But with synthetic rubber products widely available in the late 1940s and 50s, O’Neill saw an opportunity to upgrade to 20th century technology. His first forays into insulation began with a hand-sewn vest made from rubber and a two-piece, Navy surplus dry suit. Both were found lacking and by the early 1950s O’Neill began experimenting with neoprene, which had been developed by DuPont in 1930 for industrial applications. Far more flexible and supple than many other rubbers, neoprene proved to be a breakthrough material.

O’Neill refined his designs, developing a line of wetsuits that evolved though variations of cuts and zip entries. By the mid 1960s, his wetsuits, and those being sold by his rivals (most notably Bev Morgan, then Billy and Bob Meistrell of Body Glove Wetsuits), were a lynchpin of the nascent surf manufacturing industry, outselling even surfboards.

It was SCUBA divers, however, who seemed to be the earliest adopters. Ever image conscious, surfers initially considered wetsuits to be an affront to various codes of style and comportment. “When they were first introduced,” says Steve Pezman, founder and owner of The Surfer’s Journal, “I didn’t wear one for years as an act of purity.”

O’Neill, however, was an exuberant and crafty salesman and managed to gain traction with his target consumer. At expos, he would dress his adolescent children in his wetsuits and variously dunk them in a water tank, or send them scurrying across an ice block. As a pilot (he served in the Navy Air Corps after college) he was known to fly a hot air balloon emblazoned with his brand’s logo over crowds at surf contests.

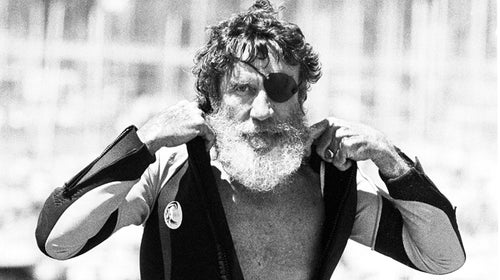

Hugh Bradner, a physicist for the University of California, Berkeley, is officially credited as the wetsuit’s inventor, but O’Neill was the product’s most colorful and memorable purveyor. He lost his left eye while testing a surf leash prototype during the 1970s and wore an eye patch for the rest of his life. With a thick beard and a slew of swashbuckling proclivities (including stints as a long shore fisherman and a biplane pilot), he literally became the face of his products. For years, his countenance served as the logo on his merchandise.

“He was kind of this affable pirate,” says surf historian and Encyclopedia of Surfing author Matt Warshaw. “He made the wetsuit cool, just through pure force of his own charisma. The eye patch and beard took it next level—his face became fascinating, and the brand got even stronger.”

O’Neill’s relocation from San Francisco to Santa Cruz in 1959 was an additional factor in the success of his products. With its frigid waters, and dedicated surf community, he found both a base of operations and a population eager to adopt his product. O’Neill’s wetsuits allowed locals to maximize their water-time and access the best surf, which typically arrives in winter. Eventually, as the wetsuit spread south, even counterculture dogmatists like Malibu’s rebel icon, Miki Dora, began embracing the technology. “One by one,” says Pezman, “we came to our senses.”

Today, O’Neill’s wetsuit company remains a hub of the wider surf industry, while Santa Cruz has risen from a 1950s backwater to a global hotbed of surf talent. Beyond Northern California, millions of surfers around the world wear a variation of the wetsuit on a daily basis. As such, O’Neill’s contributions to that crucial and insulating piece of technology have played an incalculable role in the pollination of wave riding.

“Few people have more directly affected the lives of everyday surfers than Jack O’Neill,” says Surfer magazine editor, Todd Prodanovich. “To think that so many waves around the world were off limits, or only surfable during warmer seasons, seems quaint now. But through his relentless wetsuit innovations, O’Neill opened up the colder corners of the globe to the surfing world, and allowed us to seek waves and adventure along wilder coastlines.”