The hidden scars

Emergency workers are often hailed as heroes, but a growing number are now haunted by what they see

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$19 $0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then billed as $19 every four weeks (new subscribers and qualified returning subscribers only). Cancel anytime.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 22/07/2016 (2826 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

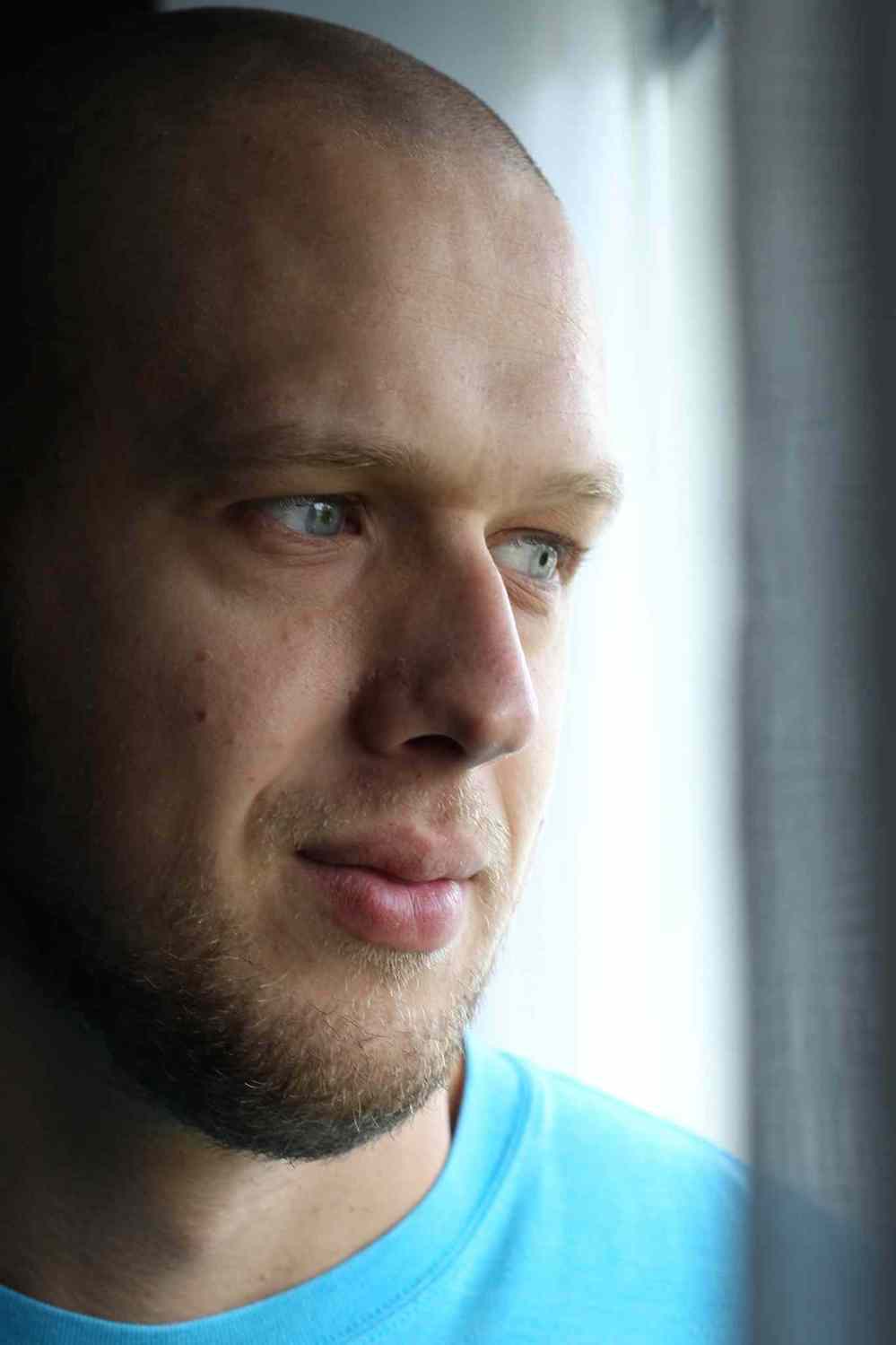

Derrick McLean is in a dark place these days. The 28-year-old corrections worker at the Manitoba Youth Centre says he’s tried to end his life at least half-a-dozen times since January.

“I just don’t even know anymore, I don’t even know what to do. I’ve tried so much different stuff. Nothing seems to help. It just seems so helpless,” McLean says.

McLean has been on medical leave for the past six months following his official diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder. He’s on a medication regime — but has often tried to overdose on the pills that are supposed to be helping him.

The first happened at the end of what would be his last shift, when he swallowed a bottle of medication, drove home and then rushed himself to hospital when he began having second thoughts.

“They kind of forced me to go off work. It wasn’t an option,” McLean says of the fallout.

It was his experiences at MYC, he says, which pushed him to a breaking point — specifically the large number of suicide attempts he’s witnessed from teen inmates over the past four years. He believes there’s been as many as 50, with another 200 high-risk incidents such as fights, threats and assaults.

“I was good at my job so they used me a lot. I was used for a lot of cell extractions, a lot of high-risk stuff,” he says.

McLean points to an incident in June 2015 where one inmate tried to hang himself. Although the boy survived, the incident stuck with him for months, ultimately leading to his breakdown.

“I’ve always been able to run in there and rip off the noose or fabric with my hands. This one was the tightest I’ve ever seen. I wasn’t able to rip it off with my hands,” McLean says. “Just that sense of not being able to control it, it stuck with me and really messed with my brain.”

McLean has now had thoughts of ending his own life in a similar way, saying he’s gone as far as to wrap a rope or fabric around his neck on several occasions.

“I kind of get there, as I’m blacking out, getting the light-headed thing, I pull myself out of it. I get these flashbacks from work on how the kids did it, and then it makes me think about doing it the same way they did it.”

McLean has been in and out of hospital ever since and goes to visit the crisis stabilization unit at least once per week.

“I don’t see it getting any better.”

* * *

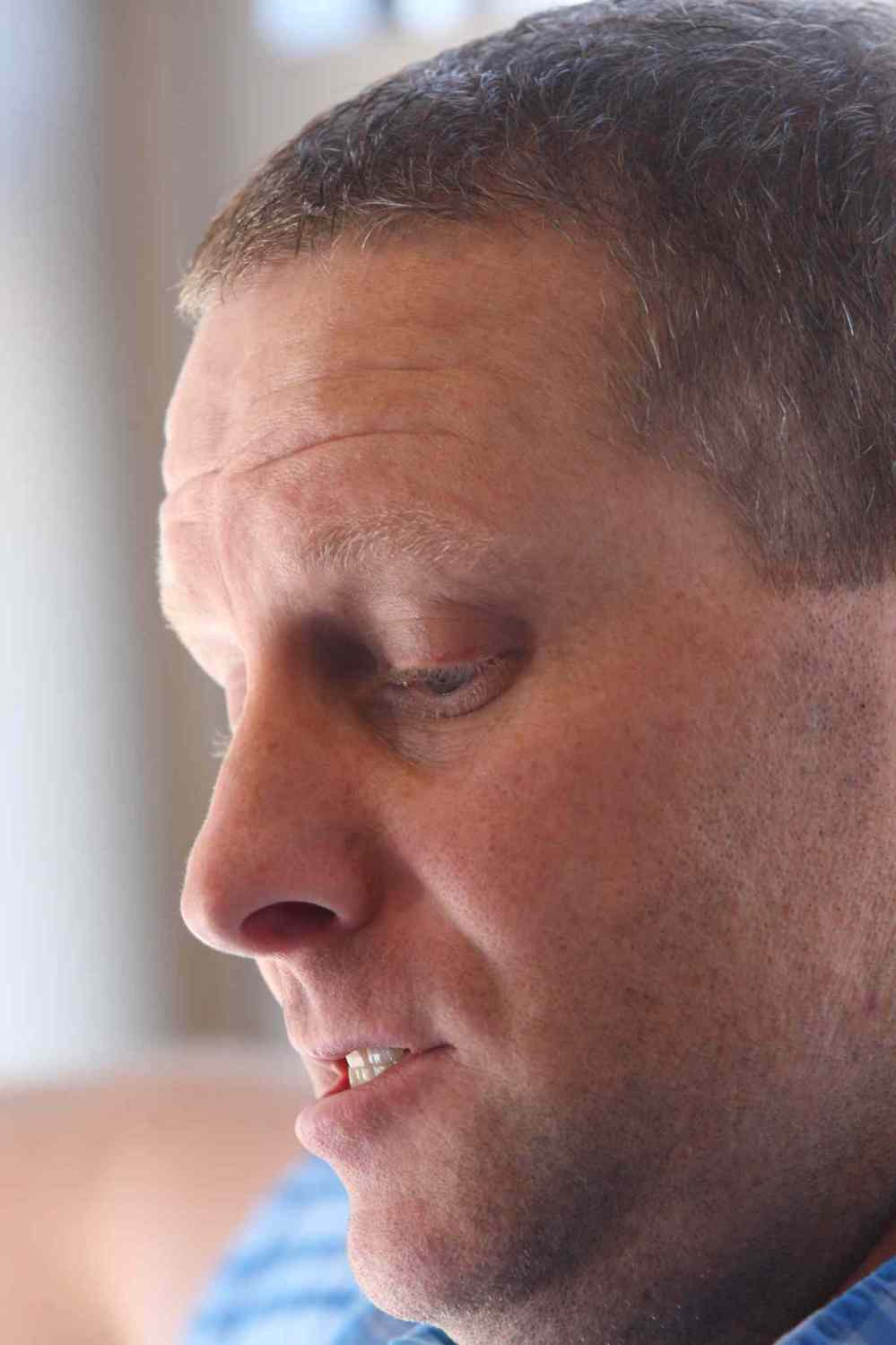

Kevin Martin has been to more awful scenes in his 15-year career as a paramedic than he cares to recount.

A North End house party where six people were shot, three fatally. Babies in full cardiac arrest. Children killed in car crashes. A Christmas call for a grandmother who had collapsed and died in front of her family as they ate a holiday meal.

Every one of them was difficult. But Martin simply did what he’s always done — quickly put it in the back of his mind, refuse to dwell on it and get ready for the next tragedy to come his way.

“I’d be the first one to basically say ‘Suck it up, buttercup.’ Everything, in the past 15 years, had rolled off this duck’s back,” he says.

All that changed during a call last month. Martin hasn’t been able to stop thinking about it. And now the 42-year-old is struggling to get through each day following a diagnosis of work-induced post-traumatic stress disorder.

“I’ve never had a call that interrupts my daily life the way this has,” Martin says.

Martin was one of the first responders on the scene June 22 when fire crews responding to a blaze on Aberdeen discovered a gravely injured man inside. It turned out to be a homicide. The 50-year-old had been brutally attacked, then the home set on fire.

The victim was pulled on to the front lawn, where Martin and his paramedic partner sprang into action.

“I could see he was black. I thought it was just soot,” says Martin. Towering trees were obscuring the street lights, making it difficult to see the victim. So they took him inside their ambulance.

“This was beyond third degree burns. His face. The sights. The smells. The magnitude of the trauma,” says Martin. There was absolutely nothing they could do.

Martin finished up his shift later that morning and went home.

“Bad call,” was all he told his wife. It’s something he’d said to her many times before. It was usually all that would be said.

Martin went to bed. But he couldn’t fall asleep. Not that morning. Not that afternoon, nor the evening. Or even the following day, when Martin called his supervisor and told him he needed to take a sick day.

His four scheduled off days followed, but Martin estimates he slept a maximum of five hours total. He wasn’t ready to go back to work for his next rotation. His wife urged him to get help.

“I was basically walking around as a zombie,” he says.

* * *

McLean and Martin may both feel very alone these days, afflicted by an emotional monster wreaking havoc with their lives. But they are part of a growing community in Manitoba – front-line emergency personnel who have been diagnosed with PTSD and related symptoms.

In the past year, there has been a spike in the number of reported cases.

Tom Wallace, the deputy chief of support services with the Winnipeg Fire Paramedic Service, says they had 41 employees take leaves in 2015 for “mental health-related” issues. That’s up from 10 in 2014, five in 2013 and just one in 2012.

“Fundamentally the nature of the work hasn’t changed, but there are more people coming forward with these concerns,” says Wallace.

Gord Perrier, deputy chief with the Winnipeg Police Service, wouldn’t provide specific numbers of officers currently on leave. But he said about 25 per cent of his members have utilized behavioural health services within the department.

The need has increased to the point they’ve now brought in a second full-time wellness officer in the past year.

“There was a demand in service. We thought we were probably overloading that (lone) individual,” says Perrier. “The office is busy on a daily basis. We’ve had a lot of reduction around that stigmatization. It’s a very public conversation in today’s world.”

WPS also employs a full-time psychologist who routinely meets with officers. A 2014 health-and-wellness survey of 400 city officers found about six per cent of them likely suffered from PTSD.

“It’s a positive thing that people are asking for help, recognizing a need for help early on, rather than things piling up and stress accumulating and having a tipping point and then a crisis situation,” says Perrier. “You can’t work in these industries without dealing with this as part of that industry life. You need to look after the people who are looking after the people.”

Alex Forrest, president of the United Firefighters of Winnipeg, says they’ve recently launched an internal campaign about PTSD for all members.

“We have a critical stress team and we are also in the process of an educational process from the rookie years to our most senior officers. We have also reached out to the spouses for assistance in identifying members with PTSD issues,” says Forrest.

Eric Glass, administrative director of the Paramedic Association of Manitoba, says there have been major strides in the past year in getting help to those who need it. He credits new legislation that came into effect in January, which made PTSD a presumptive diagnosis for front-line workers making claims through the Workers Compensation Board. No longer do they have to fight and claw to prove they are suffering. But Glass said much work still needs to be done.

“There isn’t enough emphasis, as far as I’m concerned, on preventing getting to this point,” he says.

* * *

Fred Shane makes a living getting inside the heads of troubled souls. The well-respected forensic psychiatrist has sat down with army veterans, concentration camp survivors, people impacted by residential schools and even deranged killers as part of his practice.

But Shane says he doesn’t believe society is paying enough attention to everyday people who may be most impacted these days — police, paramedics, firefighters and prison guards.

“It’s really important to continually make the public aware. I think it’s just coming to light what people like our police deal with, what our firefighters deal with. These people are forever on the line for all of us and are so vulnerable to the traumas,” Shane says.

A quick glimpse of recent world news headlines shows just how vulnerable they are. Terrorist attacks in France. Police being ambushed in the United States. Horrific child homicides like the one last week in Calgary. Infant remains being found in a Winnipeg storage locker.

“We are, on an everyday basis, being exposed to post-traumatic stress. You wake up and do a double take and say what’s happening, is this a nightmare?” says Shane. “But for most of us, our inner resilience just buries it. It goes away until the next time. And we’re able to go and cope and function,” says Shane.

That’s not the case for many who have to experience it first-hand. They can’t simply put it behind them. It can become crippling, even deadly.

“There are a certain number of individuals who become severely traumatized, and it just doesn’t go away,” says Shane. “There’s no cures for PTSD. You have to have a lot of inner resilience and resources to deal with this.”

* * *

Bryan Leach believes PTSD cost him his 14-year career. He was fired from his job as an advanced care paramedic following a 2014 incident with a patient at the Main Street Project.

Leach had been stationed at the so-called “drunk tank” and says he intervened when one guest tried to strangle himself. He jumped into the cell, along with two staff members, and quickly found himself in a battle.

The man began lashing out, and Leach responded by using a series of body blows to try and contain him. The man suffered minor injuries in the scuffle, and an excessive force complaint was filed by staff to the WFPS. Leach was ultimately dismissed despite police electing not to investigate or pursue any charges.

He’s now fighting that decision in a week-long wrongful dismissal arbitration set for this fall. WFPS management wouldn’t comment on the specific case because it remains an ongoing situation.

Leach was diagnosed with PTSD shortly after being fired and believes it contributed to his reaction at the Main Street Project. Leach had been assaulted, spit on and threatened numerous times while posted at the facility and didn’t realize at the time the impact it was having on him.

“My psychiatrist can’t point to any one event that triggered it. The way she described it is that I was coping up until then and that was the straw that broke the camel’s back,” he says. “I go in to save a guy’s life and prevent an inquest. I had every right to use self-defence. I did everything I was trained to do. And I lost my job. Fifty-nine seconds – that’s all it took to ruin my paramedic career.”

Leach was good friends with Ken Barker, a Manitoba RCMP officer who committed suicide in 2014 as a result of post-traumatic stress linked to several cases. He is now trying to ensure his illness doesn’t lead to such a breaking point.

“I’ve been in dark places, but I told myself I’d never do that, never leave them fatherless,” Leach says of his two young daughters. He sees a psychologist at least once a month, is on medication and continues to work through his trauma.

He’s compiled a list of the worst cases of his career, which he believes contributed to his PTSD. They include multiple child deaths, a house fire that claimed five lives and even a small plane crash.

“Any paramedic will tell you the kid calls are always the worst. But you can’t pick and choose what calls you go to,” he says.

* * *

Scott Wilkinson remembers going to a particularly traumatic call shortly after he began working as a Winnipeg firefighter. Upon returning to the fire hall, a supervisor told his shaken crew “You guys are OK, right?”

It wasn’t so much a question but a statement.

“Twenty years ago we didn’t talk about mental health. It wasn’t really an option to answer ‘No, actually I could use some assistance.’ We heard quotes like ‘There will be no crying in the fire hall,’” says Wilkinson, a 23-year veteran with the WFPS. “We faced the same kind of calls. But when we came back from those calls it wasn’t discussed. You just went on. And that’s where a lot of people developed some issues. We have people in retirement still dealing with issues.”

He is now part of a team working to change that. Wilkinson is the fire coordinator with the Critical Incident Stress Management team, a 60-member team of WFPS employees which works closely with all employees to ensure they are in good hands and good health.

“The attitude is much, much different now after a call. People use to view it as a weakness. It’s come a long way,” says Wilkinson. “We can’t change what happened to you, but we’re trying to change how you react to it and how it affects a person. The phrase today is building resiliency.”

Wilkinson says there are still members afraid to ask for help because of how they believe it may define them.

“There’s still a little remnant that we are the healers, the providers, the helpers, we are the strong, we will fix problems, we don’t have problems,” says Wilkinson. “But as a whole, we’re generally very resilient when you consider the amount of stuff that our people deal with on a daily basis. We have an innate capacity to deal with things.”

* * *

Jennifer Lundin has seen the impact of PTSD in her role on the Critical Incident Stress Management team.

But the advanced care paramedic has been affected in a much more personal way – her husband, PhilLaRivière, recently left the WFPS due to lingering trauma suffered on the job.

“My world, just over a year ago, came crashing down. Any and all of my coping mechanisms just completely abandoned me. I was just a shell of myself,” says LaRivière.

Depression, anxiety and even thoughts of suicide began to fill his head, shortly after responding to a fatal dog mauling call in Winnipeg in 2014. Although he’d seen worse during his 13-year paramedic career, LaRivière took this one especially hard.

He was diagnosed with PTSD, had a lengthy fight with the Workers Compensation Board to get benefits and never felt the same even after returning to desk duty following a medical leave.

“For the first while I felt like I was walking around with a sign on my forehead saying ‘Hey, look at this guy, he has PTSD, he’s broken’,” says LaRivière. “No one knew how to handle me.”

He credits his wife for being the emotional foundation he needed to get help. Lundin, who’s been on the job for 14 years, says it was a major learning experience.

“We can’t reduce our exposure. What we’re really trying to push for is recognizing those reactions in ourselves,” she says.

In her work with the critical incident team, Lundin now shares their story while hoping to make an impact with new recruits all the way up to grizzled veterans.

“We don’t want to take people’s feelings away, we want to make people healthier in dealing with their feelings, their emotions and responses,” she says. “We don’t want people to become robots. We really encourage them to pay attention to the people they work with.”

Lundin says everyone handles trauma in different ways — not unlike how you can build immunity to certain illnesses over time, only to suddenly find yourself with a flu bug.

“We have psychological immunity. Things can break it down. When that psychological immunity is lower, it just takes one incident. It doesn’t need to be a big, big incident,” she says.

LaRivière is now an advanced care paramedic instructor at Red River College and is optimistic about not only his future, but that of his former colleagues.

“It’s OK to be not OK. The stigma is being eliminated, slowly but surely. That cone of silence, that veil. But management is not always prepared, they’re not always educated or trained on how to deal with mental health,” he says.

That’s where his wife and her WFPS team comes in.

“What I think is important is that his story has a positive, hopeful outcome which I think needs to be highlighted alongside the other not as positive stories,” says Lundin. “It’s so essential to provide hope for others going through their own experience, and for people to know that there is light, there is hope, there is positivity, there is growth that can come from these experiences.”

* * *

During his first appointment with a psychologist last month, Kevin Martin was asked to estimate his distress on a scale of one-to-10. He put it at nine. Now?

“I’m comfortably around a three,” says Martin. “I’m currently working through it. The visions, they’re not as sharp. They’re kind of coming out of focus. My mind is allowing those things to go.”

One of the many exercises they do involves trying to block the bad memories. But Martin says you will never be able to remove the human element of his job, to turn paramedics such as him into emotionally-void machines or robots.

“We can’t do our job without empathy. Empathy is as important as the defibrillator and the bag and the oxygen,” he says.

Despite his progress, Martin is still not ready to return to work. He hopes that day will come soon, but he won’t rush it. He is trying to instil the tools within his own mind to deal with the next bad call he’ll respond to.

“My supervisor told me ‘I need you for the next 15 years, so I don’t care if it takes you six months or longer. Just get better’,” says Martin.

He says the type of work he does is too important to go back before you are ready.

“I’m pretty proud of what I do,” Martin told his psychologist during a recent appoint. “But I’m scared to go back to work right now. I don’t think I have the decision making ability to make critical decisions. That scared me as much as anything, because I’ve never had that.”

Martin says he’s realized everyone processes trauma differently. The call which triggered his PTSD last month didn’t have the same impact on his partner.

“There’s nothing else I want to do, but I’m scared of myself right now, and that’s not a comfortable place to be,” he says.

Martin is also taking advantage of a peer support network through the WFPS, in which dispatchers, supervisors and fellow paramedics talk regularly about what they’ve experienced. He also hopes, by sharing his own tale, to encourage others to confront their own fears.

“I don’t know if I saw myself as invincible, but I’d just never had an issue. It’s hard to admit there’s a problem,” says Martin. “I don’t want it to get any worse for me, because I see where it goes for some people. It’s not a good place to be. Going through this has really opened my eyes to how secluded you can feel when you have issues, how deep and dark things can become. Things were starting to spin out of control when it came to being able to manage day to day things.”

Despite the PTSD, Martin says he’s never considered changing professions.

“Is this career gonna chew me up and spit me out? I don’t know. I’m just trying to work through this incident,” he says.

“I’ve missed it a lot these last few weeks. I have pride that I can go out in the community, that I can help people. Some of these people are experiencing some of the worst days of their lives. Even if I can’t make the problem go away, I take in pride in knowing I can help you through it. But right now I don’t think I could.”

* * *

This wasn’t what Derrick McLean expected when he first began working at the Manitoba Youth Centre.

“It was always a dream of mine to work in justice somewhere, either police or corrections. I went and toured MYC and knew this was a place I wanted to be. I was super excited when I got into it,” he says.

But that excitement soon faded when he realized just how stressful and chaotic it would be.

“Some days you’re dealing with six or seven fights, suicide attempts…y ou’re running all night. It just drains you,” says McLean.

He puts some of that blame at the foot of management, who he says give the inmates too much power.

“They run it more like a group home for the kids to hang out and have fun. They give them so much power. It puts a lot of strain on us,” he says. “You’re expected to just deal with it and move on.”

McLean doesn’t believe the general public thinks much about corrections officers when it comes to on-the-job trauma. But he said their work is right up there with what other front-line police, paramedics and firefighters experience. It’s why they’re also included in the presumptive PTSD legislation that recently passed.

McLean says until now there’s not been a lot of dialogue in his workplace about what he, and others, are experiencing. The married father of two young children, aged five and one, is trying to change that.

“No one ever really talks about it. But everyone is struggling in some way there. I’ve just been very vocal with my struggles,” he says. “It was just a mess, I was just a wreck, I would shut down, wouldn’t talk to anybody. I was getting into drugs and stuff, just trying to cope with everything. It just completely changed me who I am. I’m not even the same person I was four years ago,” he says.

His biggest regret not seeking help earlier.

“I was always that go-to guy. Corrections has always been a bit of a don’t-talk, don’t-tell mentality. It’s kind of a forgotten job,” he says. “I would always tell myself I must be faking it, that this couldn’t be real.”

He now knows just how real it is. And while he admits to still being in a fragile state, McLean insisted on going public with his story in an attempt to help others.

“I just want people to know the stuff we’re dealing with and how it’s affecting people. I want people to know what’s going on. PTSD is a serious illness that’s killing people.”

mike.mcintyre@freepress.mb.ca

Mike McIntyre

Sports reporter

Mike McIntyre grew up wanting to be a professional wrestler. But when that dream fizzled, he put all his brawn into becoming a professional writer.