During the Democratic National Convention, supporters of Bernie Sanders denounced the superdelegate system as rigged. For their part, some Republican Party elites sought to derail Donald Trump’s nomination by changing convention rules to release already-pledged superdelegates to vote against Trump. In the face of seemingly universal denunciations of the superdelegate system, it’s worth considering its history—and its fascinating intersection with 1970s religion.

If you think the 2016 superdelegate process was rigged, then conventions in the 1960s and earlier were super-rigged. Women, minorities, and young people were regularly excluded from selection committees. In 1968, after the incumbent Lyndon Johnson withdrew, Robert Kennedy was killed, and Eugene McCarthy went AWOL, Hubert Humphrey managed to capture the Democratic nomination without winning a single primary.

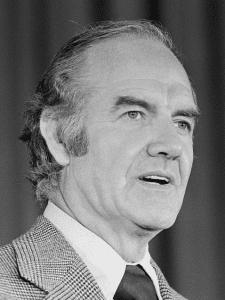

The McGovern-Fraser Commission, launched after the disastrous 1968 convention, sought to integrate minority constituent groups that had been excluded from the convention floor. By 1971 new rules had stripped mid-level state managers and local bosses of their substantial control over state primaries, leaving delegates unable to freely disregard the wishes of primary voters.

In addition to requiring that delegates be represented by the proportion of their population in each state, federal law capped the amount of individual financial contributions at $1,000. The reforms cleared the smoke-filled back rooms where veteran politicos and big-money donors ruled and opened the convention floor to African Americans, evangelicals, Hispanics, gays, opponents of the Vietnam War, senior citizens, and women.

In 1972 the new rules benefited candidate George McGovern. Energetic progressive activists, who exercised considerable influence, favored the antiwar senator. And there were suddenly a lot of them. At a time when only five percent of the nation’s population was comprised of self-identified agnostics, atheists, and people who never went to religious services, a full third of party delegates could be classified as secular.

In 1976, by contrast, the new rules primarily benefited religious conservatives who finally had their own candidate in Jimmy Carter. In Iowa’s Democratic caucuses evangelical turnout pushed Carter to the top. The insurgency stunned Floyd Giliotti, a long-time Des Moines Democratic worker and veteran of 23 caucuses over five decades. At one Carter rally, Giliotti recognized only four out of 160 people, an unusual circumstance for the old-timer; most of the new participants, he explained to the New York Times, were evangelicals. Carter went on to win the Iowa caucuses with 27% of the vote, doubling second-place finisher Birch Bayh at 13%. In Florida and other southern states, great numbers of Southern Baptists cast their ballots for Carter.

But as disillusioned evangelicals turned away from Carter in the late 1970s, the party veered again toward the cultural left. In 1980 Democratic leaders, under pressure from secularists, turned back the McGovern electoral reforms, which had inadvertently given the evangelical Carter an advantage. In an act that served to marginalize the evangelical populist activists that had upset the Democratic nomination process in 1976, party leaders introduced a complex set of policies that apportioned superdelegate votes according to demographic characteristic and political office.

It is in part this more recent change that helped the Democratic establishment keep Sanders at bay this year.