The 10 Biggest Fitness Myths

Does stretching prior to a run prevent injuries and improve performance? Does guzzling water prevent cramps? Here's the truth about the top 10 fitness myths.

Heading out the door? Read this article on the Outside app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

Chances are some bogus training advice has wormed its way into your fitness regimen. Time to root it out. Here are the ten performance myths holding you back, from pre-race stretching to the evils of high-fructose corn syrup. Plus: Three truisms that are still up for debate.

Myth #1: Stretching Prevents Injuries

Myth: Stretching Prevents Injuries

Truth: It could ruin your 10K time

In 2010, researchers at Florida State University asked ten male athletes to stretch for 16 minutes, then run for an hour on a treadmill. In a later session, the same crew sat quietly for 16 minutes, then hit the treadmill for the same duration. Without the pre-run stretch, the men covered more distance while expending less energy. The researchers’ blunt conclusion: “Static stretching should be avoided before endurance events.”

Still, the pregame ritual endures. Most of us were taught by our third-grade PE teacher that we need static stretches—like touching your toes and holding for 30 seconds—to be fast and flexible. Most physiologists now believe that when you elongate muscle fibers, you cause a “neuromuscular inhibitory response,” says Malachy McHugh, director of research for the Nicholas Institute of Sports Medicine and Athletic Trauma at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City and an expert on flexibility. By triggering this protective counter-response in the nervous system, which tightens the muscle to prevent it from overstretching, you render yourself less powerful. In experiments, static stretching temporarily decreased strength in the stretched muscle by as much as 30 percent, an effect that can last up to half an hour.

But stretching prevents injuries, right? Actually, in several large-scale studies of athletes and military recruits, static stretching did not reduce the incidence of common overuse injuries such as Achilles tendinopathy and knee pain.

Your Move: The jury is still out on the best pre-workout alternative, but dynamic stretching, which incorporates a range of body movements rather than muscle isolation, doesn’t stress tissues to the point of activating the nervous system’s protective instincts. If you’re a diehard stretcher, use this five-minute dynamic-stretching routine to warm you up for the race:

- Jumping jacks (set of 20)

- Skipping, forward and backward (one minute)

- High-leg marches: walk forward, kicking each leg up in front of you with knees locked, like a tin soldier (one minute)

- Kick your own butt: hop on one leg, kicking the other leg backward, touching your buttocks (set of ten per leg)

Myth #2: Running Barefoot Is Better

Myth: Running Barefoot Is Better

Truth: It all depends on body type and discipline

Shoes alter how we move. As soon as you put toddlers in cute little loafers, their walking changes: they take longer steps and land with more force on their heels. In the January 2010 issue of the journal Nature, Harvard scientists reported that urban schoolchildren in Kenya who wore shoes ran differently than unshod rural youngsters. Most of the urban children struck the ground with their heels, causing impact peaks, or shock waves, to travel up their legs. The barefoot runners landed lightly near the front of their feet.

A compelling finding, sure, but practically useless. Unless you were raised in the bush, you grew up wearing shoes, and as repeated biomechanical studies show, our bodies cling stubbornly to what they know. When researchers from the University of Wisconsin La Crosse outfitted recreational runners with barefoot-style running shoes, about half of the runners continued to strike the ground with their heels, just as they had in their old shoes. But if you hit with your heels and no longer have cushioning to dissipate the force, you amplify the pounding instead of reducing it. “It’s tough to relearn to run,” the scientists cautioned in their report.

Meanwhile, landing near the front of your foot, as adept barefoot runners do, can be beneficial but is no guarantee against injury. Biomechanics research shows that forefoot striking sends shock waves up your leg, too, but in a different pattern than when you heel-strike. These forces move mostly through the leg’s soft tissues instead of the bone, meaning less risk of a stress fracture—but more chance of an Achilles injury. In other words, your body takes a pounding from running, barefoot or not.

Your Move: The truth is, going barefoot can be good for your body. It all depends on your susceptibility to specific injuries and how you make the transition. If you’re ready to give it a try, experts agree you should start slowly. “Go for a typical run,” says Stuart Warden, an assistant professor at Indiana University’s School of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences. “Then take off your shoes for the last quarter of a mile.” Gradually increase the barefoot distance by a quarter-mile at the end of each run. And, above all, concentrate on form: land lightly, don’t overstride, and try not to hit the ground with your heel.

The biggest mistake barefoot newbies make is overstriding. Adopt quicker movements that cover less distance. If you’re on the fence about whether barefoot is right for you, use the following as your guide.

Will Barefoot Running Help My Injury?

- Sore Knees: Barefoot running is worth a try; it can lessen knee pain.

- Achilles-tendon problems: Barefoot running is probably not worth trying. Striking your forefoot increases stress on the Achilles.

- Heel pain or plantar fasciitis: Do not swith to barefoot running. Without perfect form, you'll be pounding that sore heel without any padding.

- Sprained ankle: Barefoot running could be beneficial after the ankle heals. Going shoeless can improve the body's pro-prioception, or spatial awareness, reducing risk of another sprain.

Myth #3: You Need to Focus on Your Core

Myth: You Need to Focus on Your Core

Truth: Core strength is probably overrated, and you risk injury by focusing too specifically on it

First off, many athletes erroneously cling to the notion that six-pack abs are a sure sign of a strong core. More to the point, it’s unclear whether core-specific training benefits athletic performance at all. In one study, a group of collegiate rowers who added an arduous eight-week regimen of core exercises to their regular rowing workouts wound up with stronger, tauter cores. But they didn’t become better rowers: their performance levels remained the same. Similarly, researchers at Indiana State University measured core strength among a group of Division I varsity football players and then had them complete sets of standard exercise drills like shuttle runs. The researchers found almost no correlation between a supercharged core and athletic performance.

What’s more, the crunch, that ubiquitous exercise that promises a solid midsection, is often harmful, because many gym rats are pumping them out with terrible form. When researchers simulated crunches using spines from pig cadavers, the spinal disks usually ruptured after a couple thousand reps. “Crunches are totally unnecessary,” says Thomas Nesser, a professor of physical education at Indiana State University.

Your Move: Core strength is important, but most people get what they need simply by practicing their sport. Common routines like squats, deadlifts, and kettlebell drills add plenty of core strength. And new studies show that running—long thought to provide little or no core benefit—does work your midsection. “Train for your sport and core strength will develop,” advises Nesser.

Myth #4: Guzzling Water Prevents Cramps

Myth: Guzzling water prevents cramps

Truth: Water and electrolytes have little to do with muscles seizing up

For years we’ve heard that exercise-induced cramping is caused by dehydration and the associated loss of sodium and potassium. We’ve been urged to load up on bananas or chug salty sports drinks before and during workouts. But in 2011, South African researchers studied hundreds of Ironman triathletes, a group frequently felled by muscle cramps. To check for signs of clinical dehydration, researchers took blood samples just prior to the event’s start, for measuring levels of sodium and other electrolytes, then drew blood again at the finish line. Forty-three of the Ironmen cramped during the race, but the afflicted were no more dehydrated than the other competitors were, and they had comparable electrolyte levels. The principal difference between the two groups was speed: the tested group finished faster.

A team of scientists at North Dakota State University in Fargo reached similar conclusions. In a 2010 study, the researchers asked a group of fit young men to fill up with water, then induced cramping by zapping them with a series of low-level electric pulses. They did the same after the men rode stationary bikes in a heat chamber, with some of them losing up to 3 percent of their body weight to sweat. Since it took the same number of electrical shocks to induce cramping again, the spasms “were likely not caused by dehydration,” says professor Kevin Miller, who led the study. Instead, he believes that muscle cramps are due to exertion, fatigue, and a cascade of accompanying biochemical processes.

Get over it: Miller can’t tell you how to eliminate cramps altogether—there isn’t enough research—but stretching seems to be the best option to relieve acute cramping once it’s set in. That and pickle juice. In one of Miller’s recent studies, cramp-stricken cyclists who drank 2.5 ounces of it recovered 45 percent faster than those who drank nothing. Miller speculates that something in the acidic juice disrupts the nervous-system melee in the exhausted muscle.

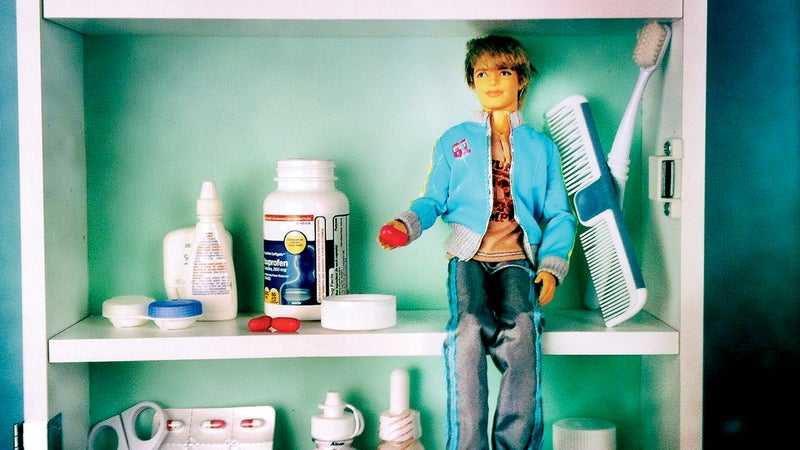

Myth #5: Popping Ibuprofen Prevents Soreness

Myth: Popping ibuprofen prevents soreness

Truth: It does more harm than good

At the 2006 Western States 100, an ultra-endurance marathon in Squaw Valley, California, seven of ten racers polled said they had swallowed ibuprofen before or during the race, while almost 60 percent of racers polled at the 2008 Brazil Ironman said they popped painkillers. “It’s become part of their ritual of getting ready,” says Stuart Warden, director of the Center for Translational Musculoskeletal Research at Indiana University and an expert on rehabilitation of sports-related injuries.

After the Western States race, however, competitors who’d used ibuprofen were just as sore as those who hadn’t. Surprisingly, they also displayed more blood markers of inflammation than other competitors, even though ibuprofen is an anti-inflammatory. Recent work from others has suggested that frequent use of painkillers can blunt the ability of muscles to adapt to exercise. In a 2010 study of distance-running mice, researchers determined that “ibuprofen administration during endurance training cancels running-distance-dependent adaptations in skeletal muscle.” In other words, the rodents’ muscles stopped building strength in response to the training. In an editorial in the British Journal of Sports Medicine in 2009, Warden went so far as to say that “ritual use” of ibuprofen “represents misuse.”

Your Move: Don’t take ibuprofen unless you have a legitimate injury. Muscle pain is part of the body’s training response, and nothing has been shown to effectively ward it off.

Myth #6: Dehydration Hurts Performance

Myth: Dehydration hurts performance

Truth: Overhydrating is more likely to sabotage your personal record.

In the 1990s, endurance athletes were advised to stay ahead of their thirst and drink as much as they could stand during training and races. A decade later, almost everyone had been schooled with the knowledge that hydrating to excess can cause hyponatremia—essentially, intoxication caused by consuming too much water, a potentially fatal condition in which cells swell with the excess fluid.

However, whether dehydration is equally troublesome and a hindrance to peak performance remained up in the air. But according to a 2011 review of time-trial studies of dehydration, losing up to 4 percent of body weight during exercise does not alter performance. Results from endurance events seem to bear that out: during the 2009 Mont-Saint-Michel Marathon in France, researchers measured the weight loss of 643 competitors and compared it with their finish times. The runners who lost the most water weight were also the fastest. Most of those who finished in less than three hours lost at least 3 percent of their body weight to sweat.

Your Move: “Drink when you feel thirsty,” says James Winger, M.D., assistant professor at Loyola University’s Stritch School of Medicine in Chicago, who conducted a survey of distance runners last year and found that misconceptions about hydration were rampant, even among endurance athletes. “Thirst is an exquisitely finely tuned indicator of your body’s actual hydration status,” Dr. Winger says. “Listen to it.”

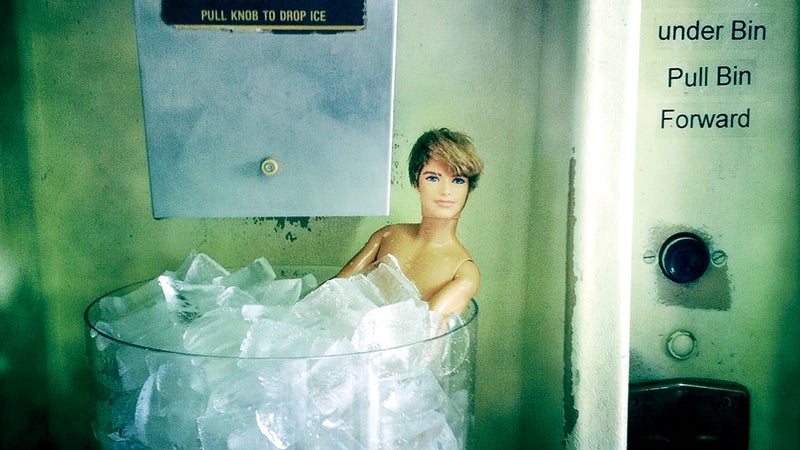

Myth #7: Ice Baths Speed Recovery

Myth: Ice baths speed recovery

Truth: They're not worth the chill

Many elite athletes, from marathoners to gridiron stars to starting pitchers, practically swear by icing up as a way to promote healing. But this nearly universal post-race/game/workout ritual now looks like nothing more than proof that the placebo effect is alive and well. In a 2007 study in the Journal of Sports Sciences, men who completed a punishing 90-minute shuttle run and then eased themselves into a 50-degree bathtub for ten minutes told researchers afterward that they were sure they were less sore than they would have been without the bath. Yet their levels of creatine kinase, a hallmark of muscle damage, remained the same as in runners who hadn’t soaked. Also in 2007, in one of the few randomized controlled tests examining the popular practice, 40 volunteers did seated leg extensions until near exhaustion. Afterward, half sat in lukewarm water while the other half sat in an ice bath. Next day, those who’d ice-bathed were just as sore as the control group. In fact, the ice bathers reported more pain than the others during a test in which they were asked to rise out of a chair using their tired leg for support. The authors concluded that the “protocol of ice-water immersion was ineffectual.”

Get over it: If you like freezing your butt off, soak away, but the benefits are strictly psychological. Any physiological effects won’t last longer than the ice itself.

Myth #8: Long and Slow Burns More Calories

Myth: Long and slow burns more calories

Truth: You need to pump up the intensity

For years it’s been assumed that you eliminate more lipids in the magical fat-burning zone—exercising between 68 and 79 percent of your maximum heart rate—than when you really exert yourself. Why? Because, the theory went, low-intensity exercise allows the body to fuel itself from the midsection rather than from readily available food calories.

But a report by David Nieman, a professor in the Human Performance Laboratory at Appalachian State University in North Carolina, showed that strenuous exercise burns more calories per minute than easy sessions. Which isn’t surprising: higher intensity equals more calories. But that study also determined that intense exercise increases your metabolism for up to 14 hours afterward. In other studies, light-duty exercise produced no such caloric afterburn. “We’ve become a nation of exercise wimps,” Nieman says. “Too many people don’t bother or are afraid of exercising hard. But intensity is probably the only way to lose weight with exercise.”

Your Move: Start sprinkling high-speed intervals into your slow runs. Do hill repeats on your bike. Try to maintain a heart rate at or above 80 percent of your max for about 45 minutes several times a week.

Myth #9: Fructose Is a Performance Killer

Myth: Fructose is a performance killer

Truth: Fructose can be a performance superfuel

The warnings are stern: avoid fructose, especially in the form of high-fructose corn syrup, because it’s contributing to an obesity epidemic. And the evidence is strong that people who are sedentary should avoid it. But for active individuals, it’s a different story. “All athletes who compete or train for a period longer than 45 to 60 minutes will improve their performance by ingesting a solution containing carbohydrates,” or sugar, says Luc van Loon, a professor in the Department of Human Movement Sciences at Maastricht University Medical Centre in the Netherlands. And you’ll get more performance bang if that sugar is, in part, fructose. When cyclists in a British study drank a beverage containing both fructose and glucose (a simple sugar that typically appears on labels as maltodextrin), they rode almost 8 percent faster during a time trial than riders who drank fluids with glucose alone. “Fructose and glucose are taken up in the intestine by different transport proteins,” van Loon says. “This allows for a more rapid uptake of carbohydrates from the gut.” Which means you have more calories available to you more quickly if you drink or eat carbohydrates containing fructose.

Most high-fructose corn syrup contains approximately equal portions of glucose and fructose and is perfectly acceptable for athletes. The concerns about high-fructose corn syrup have more to do with the highly processed foods they often show up in rather than the intrinsic characteristics of the sugar. The drawback for endurance athletes is that the ideal ratio of glucose to fructose is 2:1 (not the 1:1 of corn syrups). “There are very few drinks on the market that provide that perfect mix,” says Asker Jeukendrup, a professor of exercise metabolism at the University of Birmingham in England, who led the study of cyclists.

Your Move: Read labels. Some drinks, such as PowerBar’s Ironman Performance beverages, tout their 2:1 glucose-fructose mix. For do-it-yourselfers, sports nutritionist Nancy Clark’s homemade sports drink, from the fourth edition of her Sports Nutrition Guidebook, is an ideal performance boost. Gather together these ingredients:

- 1/4 cup sugar

- 1/4 teaspoon salt

- 1/4 cup orange juice

- 2 tablespoons lemon juice

Then, in a quart pitcher, dissolve the sugar and salt in ¼ cup hot water. Add the orange and lemon juice and 3 1/2 cups cold water.

Myth #10: Supplements Help Performance

Myth: Supplements help performance

Truth: There’s no such thing as a magic pill. (At least a legal one.)

Antioxidants, Including Vitamins A, C, and E

Conventional Wisdom: They destroy free radicals, molecules created during exercise that are thought to contribute to cell damage.

Science Says: According to recent studies, some free radicals appear to trigger chemical reactions that actually help strengthen muscles after exercise and improve health. So taking antioxidants in excess may curb the benefits of exercise.

Quercetin

Conventional Wisdom: A flavonoid found naturally in apples, red wine grapes, and other fruits and vegetables, it’s thought to improve endurance capacity and fight fatigue.

Science Says: Athletes get little or no benefit from it. An upcoming review of seven studies concluded that quercetin may be useful for out-of-shape people who start exercising but does next to nothing for the already fit.

Creatine

Conventional Wisdom: It’s the most popular supplement in the country, and power athletes insist it helps build muscle strength and bulk.

Science Says: It does—to a point. College football players who used creatine bench-pressed more weight, and Australian soccer players sprinted faster. But if you’re an endurance athlete, creatine draws extra water into cells, leading to diarrhea and even cramping.

DHEA

Conventional Wisdom: DHEA raises testosterone levels and helps build muscle and increase power.

Science Says: Yes and no. DHEA is a naturally occurring hormone that affects the body’s ability to produce testosterone. But a 2006 study in the New England Journal of Medicine found that daily doses in men with normal levels did not increase muscle strength.

Up for Debate

Massage Boosts Recovery

In a 2010 study, Canadian researchers had 12 healthy young men squeeze a hand grip until their arm muscles were spent, then had a certified sports-massage therapist give half of them a rubdown. The other half received no such pampering. Surprisingly, the massages did not increase blood flow to the men’s muscles—one of the primary reasons athletes seek bodywork after a strenuous workout. Additionally, researchers concluded that a massage “actually impairs removal of lactic acid from exercised muscle.”

Missing Link: Studies are needed that examine whether post-exercise massage might have other benefits. Most athletes swear they feel better after being kneaded, but so far there’s no evidence at the cellular level to justify the indulgence.

Surgery is best for an ACL tear

A landmark study on torn ACLs published in 2010 in the New England Journal of Medicine led to heated disagreement about the effectiveness of going under the knife. Researchers randomly assigned either surgery or physical therapy to a group of 121 active adults who’d suffered an ACL tear. After two years, the groups’ knees were similar in terms of function and pain, showing that there was little advantage to the surgery.

Missing link: Finding a better way to repair wracked knees. While plenty of athletes have come back from an ACL tear at an extremely high level—surgery and physical therapy can usually restore basic knee stability—many never reach peak performance again. In current ACL surgery, injured tissue is often replaced. But some surgeons are experimenting with reconstructing the ligament with new forms of tissue grafts, which could produce better long-term outcomes.

Cortisone Shots Speed Healing

Although they can provide immediate pain relief for soft-tissue injuries such as tennis elbow and Achilles tendinopathy, the shots can slow healing over the long term, according to a number of new studies. A comprehensive review of the available research published last year found that people who’d received cortisone shots had a much lower rate of full recovery than those who’d done nothing at all. Plus, they had a 63 percent higher risk of relapse.

Missing link: Trying to figure out exactly what’s going on inside overtaxed tendons and ligaments. In fact, scientists don’t fully understand the mechanics of injuries like tennis elbow and Achilles problems, so they don’t know how best to treat them—except to say that cortisone shots don’t appear to do the trick.