Over the past week, the fabled Kohinoor diamond has been back in the news. The Indian government told the court that the diamond was “gifted” and not forcefully taken away by the British. The statement acted as a catalyst to a fervent debate on whether the precious rock should finally be brought back to India.

IndianExpress.com consulted historian/author William Dalrymple — currently working on his forthcoming non-fiction history book, koh-i-nur along with Anita Anand — to understand the complex history of the diamond. He spoke about the ambiguous position that the Kohinoor holds in India’s history, issues of national pride and historical consciousness that is part of the ensuing debate surrounding it.

“While I was working on my previous book on Shah Shujah Durrani’s (ruler of the Durrani empire in present day Afghanistan from 1803-1809) life, I got some Persian manuscripts back from Kabul. I came across this chapter between the time Nadir Shah (Shah of Persia) left India and when the diamond came back to India with Maharaja Ranjit Singh. So this was information on the Kohinoor that people did not know about, through Afghan sources,” says Dalrymple as he explains his point of interest in the Kohinoor.

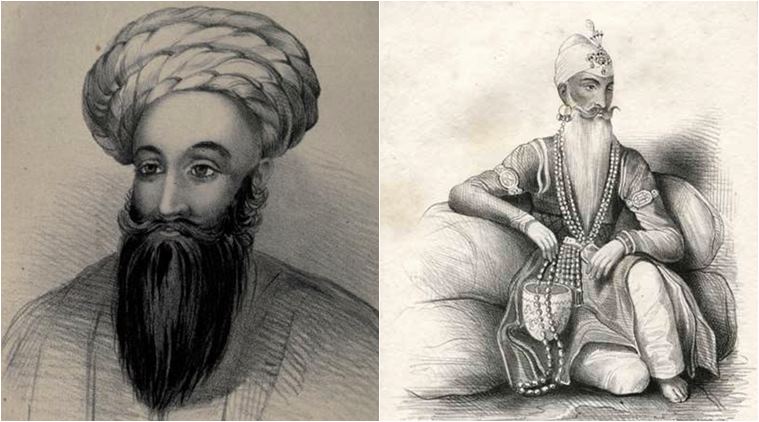

He goes on to explain why it is important to keep in mind that his interest in the Kohinoor stemmed out of information he found in manuscripts he got from Afghanistan.“The Indian case rests on the claim that the British took away the diamond by force. I think there is no doubt about that. It is complete nonsense that it was gifted by Maharaja Ranjit Singh of the Sikhs. Maharaja Ranjit Singh kept it with him his whole life. It was during the regency of his son Duleep Singh that the diamond was taken away. There is not much to dispute about that. It was part of the peace treaty of the British and was handed over in the process of the defeat of the Sikhs as one of the spoils going to the victor.”

“However, what complicates this is that the diamond did not come peacefully to Ranjit Singh either. Indians claim that Shah Shujah gave the diamond to Maharaja Ranjit Singh. But Shah Shujah’s autobiography clearly mentions that his son was tortured by Maharaja Ranjit Singh before he took away the diamond. So if the Indian case rests on the claim that the British took it by force, so did the Indians.”

Shah Shujah Durrani (left) and Maharaja Ranjit Singh (right) Source: Wikimedia Commons

Shah Shujah Durrani (left) and Maharaja Ranjit Singh (right) Source: Wikimedia Commons

By the time the Kohinoor reached the British in the mid nineteenth century, it had already passed through a number of hands, all of which were not “Indian”. “By the time the diamond passed from the Afghans to Maharaja Ranjit Singh, the diamond had been with the Afghans of the Durrani empire for two to three generations. It kept getting transferred peaceably through each generation and finally came into the possession of Shah Shujah. Shah Shujah in his autobiography mentions that his son was tortured and that he was starved for days by Ranjit Singh in order to get the diamond,” says Dalrymple.

In Dalrymple’s views, if India could lay claims on the diamond, then so could a number of other countries like Iran and Afghanistan. Considering that the time at which the diamond was being passed along hands of different rulers, national boundaries was not well demarcated, it complicates the claims made on it even further. At the time that Nadir Shah attacked India and acquired the Kohinoor, Kabul and Kandahar were being ruled from Delhi. Pakistan and parts of Afghanistan were part of India. In fact there are three lawsuits in Pakistan seeking to reclaim the Kohinoor.

The Kohinoor, which definitely originated in India’s Golconda mines, was passed on to the Persians through Nadir Shah long before the British looted the Sikhs. “The great looting of the Mughals was not by the British. By the times the British are powerful, the Mughals have already lost everything to the Persians. While the British did loot India, particularly Bengal, the big looting was done by Nadir Shah,” he says.

“It in only because of the way the British wrote history that people have remembered the Kohinoor while everything else is forgotten. Other objects of loot like the Darya Noor (which is a sister diamond of Kohinoor) and parts of the Peacock throne are in Iran and nobody speaks about it.”

Nader Shah (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Nader Shah (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

While it is evident that the history of the Kohinoor is complex and difficult to lay claims upon, the way people remember history is far more complicated. Dalrymple talks about how some events and objects in history always manage to grab more attention than others and there is no particular reason for that.

Giving an explanation on what role the Kohinoor plays in making Indians feel patriotic, Dalrymple says “it’s part of historical memory. It becomes a symbol of the British looting of India. However, it is the wrong object to focus upon due to its complicated history.”

Speaking about the process of reclaiming the Kohinoor by India, he says that there is not much progress to be made by such a move. “It will be a matter of national pride, but it will open up a large number of grievances. Should the Dravidians now put a lawsuit against the Aryans, or should the Shudras start suing the Brahmans? The Kohinoor is a symbol of how complex and intractable history is. History is full of horror stories.”

“My personal view of all this is that history is far too complicated and entangled to think that there is anything to be gained by asking for retribution. Where does one stop? Should Britain seek retribution from Norway and Sweden for the Viking raids? Equally, should the Sri Lankan government send a bill to India for the Chola raids of Anuradhapura? This is not a healthy way of conducting international relations. One should be educated in history in the least biased way possible.” he says.

The job of the historian is never to correct history, but to analyse it and learn from it.