Wolfgang Paalen, a big-league European surrealist, and Emily Carr, the great Canadian modernist, met at her studio in Victoria in August 1939.

Wolfgang Paalen, a big-league European surrealist, and Emily Carr, the great Canadian modernist, met at her studio in Victoria in August 1939.

This sounds like a momentous event. Their time together is the focus of a new exhibition at the Vancouver Art Gallery, and a book written by guest curator Colin Browne. Paalen and his wife and sponsor visited Carr three times in quick succession, and they took her out to dinner at the Empress. Both Carr and Paalen are interesting artists, but it’s hard to see that their meeting added up to anything very significant.

Browne contributed an essay to the 2011 Vancouver Art Gallery exhibition entitled The Colour of My Dreams, pursuing European surrealism’s profound interest in the indigenous arts of the Pacific Northwest. Paalen was among the artists included in the Vancouver show and is now taken up at length.

As an artistic movement, surrealism made efforts to look into those unconscious interior realms proposed by Freud and Jung. They did this by two methods: some juxtaposed “realistic” elements in irrational combinations, like the famous umbrella and sewing machine on an operating table. Others tried to leap over the rational mind by “automatic” drawing and the inspiration of chance.

Paalen was one of the latter, creating paintings based on the deposits of candle soot on canvas, which he called “fumage.” Like many of his fellow artists in Paris, he found the carvings of indigenous societies mysterious and liberating. Societies living in a prehistoric communal age, uncorrupted by western civilization, provided “a channel of communication from an archaic past to an uncertain future,” as Browne writes. The situation in Europe at that time was, of course, dire.

With his sponsor, Eve Sulzer, and his wife, the poet Alice Rahon, Paalen set out in 1939 for the new world to collect some inspiring indigenous art. Beginning at the American Museum of Natural History in New York, he then went to Ottawa to visit anthropologist Marius Barbeau. Following Barbeau’s advice, they took the train to Winnipeg, Banff, the Skeena River and eventually to Wrangell, Alaska.

Paalen was well advised, and bought about 40 First Nations pieces, including a four-metre-tall red cedar partition painted in about 1840 for Chief Shakes’ Grizzly Bear House in Wrangell. According to Browne, Paalen “regarded indigenous art works not as souvenirs of an irretrievable past, but as luminous guides for a world that would have to renew itself by understanding the best of what it had destroyed.”

Paalen was more than a painter, Browne explained. “As a philosopher he perceived in Northwest Coast art a conceptual system based on what western physics was only just beginning to discover: the universal interconnectedness of all things.”

Sent with an introduction to Carr by Barbeau, Paalen and his companions spent a few days in Victoria after their trip up north. It was August 1939. Carr enjoyed a visit from the young artist, who had just been to the places that she painted up the coast. She was then 67 years old, and surprisingly open to new ideas. After her heart attack in 1937, she was now worried about her legacy and wondered how much longer she could go on painting.

As it happened, after Paalen’s visit and before her death in 1945, she managed to write seven books, and paint many new and vigorous pictures. She might have taken some encouragement from Paalen’s enthusiasm. Browne astutely points out that Carr and Paalen had a key point in common.

Back in 1910, Carr had studied in France with Henry Phelan Gibb. At that point, she began using oil paint and bold colours. “She began to shift her attention from visual perception to the inner image,” Browne notes. Later, she had an exhibition in Ottawa in 1927, and was encouraged by Lawren Harris. Carr began to experiment, borrowing freely from the contemporary artists of her generation.

Harris suggested that Carr put aside the “Indian paintings” and seek an equivalent in the coastal landscape. About that time, she hosted workshops at the House of All Sorts with Seattle artist Mark Tobey, later a seminal abstract expressionist. Tobey counselled her to “paint from inside herself,” and she began to sketch and paint with a new urgency, using oil and gasoline, a more expressive medium.

Paalen himself was transformed by his trip to the Northwest. He now focused on the recognition that the inner and outer worlds are one, the essence of the new atomic age. “His granular explorations of cosmic movement and perpetual transformation opened the door to young painters in New York,” Browne wrote, “poised to expand beyond conventional dimensions of language and representation.” Thus was abstract expressionism born.

All very interesting — but what does this add to our understanding of Emily Carr? According to Browne: “Emily Carr found surrealism objectionable, a reaction exacerbated by its popularity and its apparent concentration on erotic fantasies.”

It’s not clear if Carr had ever seen a surrealist artwork, though at the time J.W.G. Macdonald was smitten with automatic painting in Vancouver. But she never saw Paalen’s artworks. “I can’t get the surrealist point of view,” she wrote in a letter to John David Hatch, a museum director in Albany, New York. “Most of their subjects revolt me — seems as if their minds must be askew somewhere.”

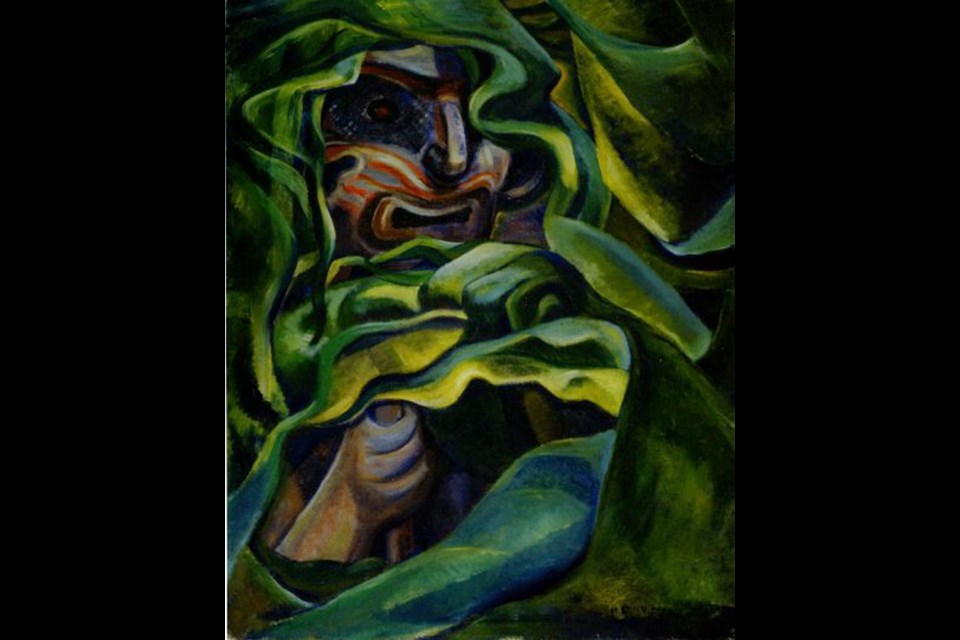

In the exhibition, Browne matches paintings by Carr and Paalen, inviting comparison. Here were two artists who “opened themselves to the pulsing rhythms of cosmic energy that coursed through all inert and living things … to manifest the felt within the seen,” Browne concluded. One can read into them a certain similarity, but I don’t think he had any influence on her. The book serves as a footnote to the Emily Carr legend, rather than a major new theme.

To his credit, Paalen bought one of Carr’s paintings while in Victoria. And after visiting her, he went to Mexico, where he met Diego Rivera and Freda Kahlo, and publicly renounced surrealism.

The exhibition will run until Nov. 13 at the Vancouver Art Gallery, 750 Hornby St. in Vancouver. The book is published by Figure.1 Publishing, Vancouver, 82 pp., $24.95.