The Last Days of Stealhead Joe

The Deschutes River fly-fishing guide called Stealhead Joe was an angling master with a long list of devoted clients. But as Ian Frazier, who fished with Joe last fall, learned, off the water, Joe’s life was a tangle of troubles that ultimately overwhelmed him.

Heading out the door? Read this article on the Outside app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

The police report listed the name of the deceased as Joseph Adam Randolph and his age as 48. It did not mention the name he had given himself, Stealhead Joe. The address on his driver’s license led police to his former residence in Sisters, Oregon, where the landlord said that Randolph had moved out over a year ago and had worked as a fishing guide. In fact, Randolph was one of the most skilled guides on the nearby Deschutes River, and certainly the most colorful—even unforgettable—in the minds of anglers who had fished with him.

He had specialized in catching sea-run fish called steelhead and was so devoted to the sport that he had a large steelhead fly with two drops of blood at the hook point tattooed on the inside of his right forearm. The misspelling of his self-bestowed moniker was intentional. If he didn’t actually steal fish, he came close, and he wanted people to hear echoes of the trickster and the outlaw in his name.

I spent six days fishing with Stealhead Joe in early September of 2012, two months before he died. I planned to write a profile of him for this magazine and had been trying for a year to set up a trip. Most guides’ reputations stay within their local area, but Joe’s had extended even to where I live, in New Jersey.

Somehow, though, I could never get him on the phone. Once, finding myself in Portland with a couple of days free, I drove down to Sisters in the hope of booking a last-minute trip, but when I asked for him at the Fly Fisher’s Place, the shop where he worked, I was told, in essence, “Take a number!” Staffers laughed and showed me his completely filled-out guiding schedule on a calendar on an office door, Joe himself being unreachable “on the river” for the next x days.

The timing sorted itself out eventually. Joe and I spoke, we made arrangements to fish together, and I met him in Maupin, a small town on the Deschutes about 90 miles from Sisters. Joe had moved to Maupin for personal and professional reasons by then. On the day we met, a Sunday, I called Joe at nine in the morning to say I was in town. He said he was in the middle of folding his laundry but would stop by my motel when he was done. I sat on a divider in the motel parking lot and waited. His vehicle could be identified from far off. It was a red 1995 Chevy Tahoe with a type of fly rod called a spey rod extending from a holder on the hood to another holder on the roof like a long, swept-back antenna.

I have seen a few beat-up fishing vehicles and even owned one or two of them myself. This SUV was a beaut, and I chuckled in appreciation as Joe got out, introduced himself, and showed me its details. The Tahoe’s color was a dusty western red, like a red shirt that gets brighter as you slap dust off of it. (To maintain that look, he deliberately did not wash his vehicle, a girlfriend of Joe’s would later tell me.) The grille had been broken multiple times by deer Joe had hit while speeding down country roads in predawn darkness in order to be on the water before everybody else, or returning in the night after other anglers had gone home. He had glued it back together with epoxy, and there was still deer hair in the mends.

Hanging from the inside rearview mirror was a large red-and-white plastic fishing bobber on a loop of monofilament line, and on the dash and in the cup holders were coiled-up tungsten-core leaders, steelhead flies, needle-nose pliers—“numerous items consistent with camping and fishing,” as the police report would later put it. While Joe and I were admiring his truck, I didn’t guess I was looking at the means he would use to take his life. He died in the driver’s seat, which he pushed back into its full reclining position for the occasion. The report gave the cause of death as asphyxiation from carbon-monoxide poisoning.

Something momentous always seems about to happen in canyon towns like Maupin, where the ready supply of gravity suggests velocity and disaster. Above the town, to the east and west, the high desert of central Oregon spreads its dusty brown wheat fields toward several horizons. Below the town, in a canyon that is wide in some places and narrow in others, 4,500 cubic feet per second of jade-colored river go rushing by.

Four-hundred-some people live in Maupin in the winter; several thousand might occupy it on any weekend from June through Labor Day. People come to whitewater raft, mainly, and to fish. Guys plank on bars in the wee hours, tequila shots are drunk from women’s navels, etc. Sometimes daredevils pencil-dive from Maupin’s one highway bridge; the distance between the Gothic-style concrete railing and the river is 98 feet. They spread their arms and legs in the instant after impact so as not to hit the bottom too hard.

Maupin, an ordinary, small western town to most appearances, actually deals in the extra-ordinary. What it offers is transcendence; people can experience huge, rare thrills around here. Fishing for steelhead is one of them.

Fishing from a boat is not allowed. You wade deeper than you want, and then you cast, over and over. You catch mostly nothing.

Steelhead are rainbow trout that begin life in fresh-water rivers, swim down them to the ocean, stay there for years, and come back up their native rivers to spawn, sometimes more than once. They grow much bigger than rainbows that never leave freshwater, and they fight harder, and they shine a brighter silver—hence their name.

To get to the Deschutes from the ocean, the steelhead must first swim up the Columbia River and through the fish ladders at the Bonneville Dam and The Dalles Dam, massive power-generating stations that (I believe) add a zap of voltage to whatever the fish do thereafter. Some are hatchery fish, some aren’t, but all have the size, ferocity, and wildness associated with the ocean. “Fishing for steelhead is hunting big game,” says John Hazel, the senior of all the Deschutes River guides and co-owner of the Deschutes Angler, a fly shop in Maupin.

Steelhead are elusive, selective, sometimes not numerous, and largely seasonal. They seem to prefer the hardest-to-reach parts of this fast, rock-cluttered, slippery, rapid-filled, generally unhelpful river. On the banks, you must watch for rattlesnakes. Fishing from a boat is not allowed. You wade deeper than you want, and then you cast, over and over. You catch mostly nothing.

Casting for steelhead is like calling God on the telephone, and it rings and rings and rings, hundreds of rings, a thousand rings, and you listen to each ring as if an answer might come at any moment, but no answer comes, and no answer comes, and then on the 1,001st ring, or the 1,047th ring, God loses his patience and picks up the phone and yells, “WHAT THE HELL ARE YOU CALLING ME FOR?” in a voice the size of the canyon. You would fall to your knees if you weren’t chest-deep in water and afraid that the rocketing, leaping creature you have somehow tied into will get away.

Joe's other nicknames (neither of which he gave himself) were Melanoma Joe and Nymphing Joe. The second referred to his skill at fishing for steelhead with imitations of aquatic insects called nymphs. This method uses a bobber or other floating strike indicator and a nymph at a fixed distance below it in the water. Purists don’t approve of fishing this way; they say it’s too easy and not much different from dangling a worm in front of the fish’s nose.

For himself, Joe believed in the old-time method of casting downstream and letting the fly swing across the current in classical, purist style. But he also taught himself to nymph, and taught others, and a lot of Joe’s clients caught a lot of fish by this method. In one of Joe’s obituaries, Mark Few—Joe’s prized and most illustrious client, the coach of the highly ranked men’s basketball team at Gonzaga University, whom Joe called, simply, “Coach,” who liked to catch a lot of fish, and who therefore fished with nymphs—praised Joe’s “open-mindedness” as a guide.

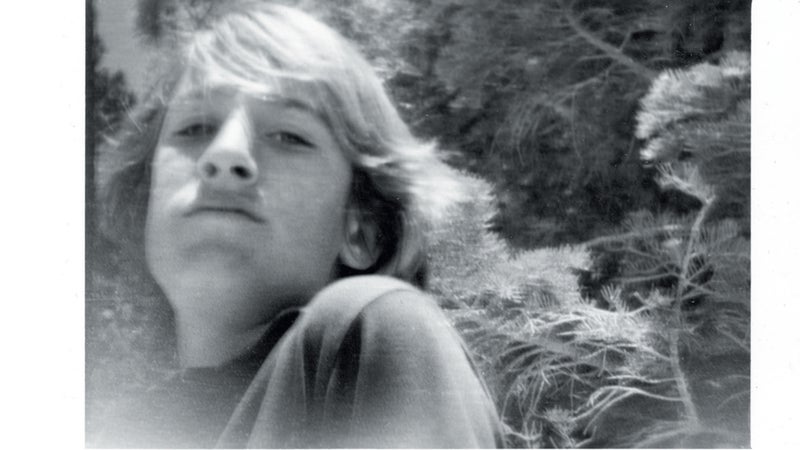

The nickname Melanoma Joe came from Joe’s habit of fishing in board shorts and wading boots and nothing else. Most guides long-sleeve themselves, and lotion and hat and maybe glove themselves, and some even wrap a scarf around their heads and necks and faces like mujahedeen. Joe let the desert sun burn him reddish brown. Board shorts, T-shirt, sunglasses, baseball cap, flip-flops—that was his attire when we met. He grew up mostly in California and still looked Californian.

He smoked three packs of Marlboros a day.

For a guy as lost as Joe must have been, he gave off a powerful fatherly vibe. Even I was affected by it, though he was 13 years my junior. An hour after we met, we waded out into the middle of the Deschutes in a long, straight stretch above town. The wading freaked me out, and I was frankly holding on to Joe. He was six-five, broad shouldered, with a slim, long-waisted swimmer’s body. I wore chest waders, and Joe had put on his waders, too, in deference to the colder water. I held tightly to his wader belt. Close up, I smelled the Marlboro smell. When I was a boy, many adults, and almost all adult places and pastimes, smelled of cigarettes. Joe had the same tobacco-smoke aroma I remembered from dads of fifty years ago. I relaxed slightly; I might have been ten years old. Joe held my hand.

That day we were in the river not primarily to catch fish but to teach me how to cast the spey rod. I had been dreading the instruction. Lessons on how to do any athletic activity fail totally with me. Golf-coach reprimands like “You’re not opening up your hips on the follow-through” fall on my ears as purest gibberish, talking in tongues, like the lost language of a tribe of Israel that has been found again at Pebble Beach—

—Where Joe was once a golf pro, by the way, as he told me in passing. The only athletic enterprises he had never tried, he said, were boxing and wrestling. Now he demonstrated to me the proper spey casting method. Flourishing the rod through positions one, two, three, and four, he sent the line flying like a perfect tee shot down fairway one. From where we were standing, above our waists in water, it went 90 feet, dead straight. You could catch any fish in the river with that cast.

Regular fly-casting uses the weight of the line and the resistance of the air to bend the rod—or “load” it—so that a flick of the wrist and arm can release the tension and shoot the line forward. Spey casting, an antique Scottish technique from the heyday of waterpower, uses a longer rod, two hands, and the line’s resistance on the surface of the river to provide the energy. You lay the line on the water beside you, bring the rod up, sweep it back over the line against the surface tension, and punch it forward with an in-out motion of your top and bottom hands. The spey cast is actually a kind of water-powered spring. It throws line farther and better than regular fly-casting does, and because it involves no backcast it is advantageous in closed-in places like the canyons of the Deschutes.

If Joe showed any signs of depression in the first days we fished together I did not notice them. Walking along the railroad tracks beside the river on our way to a good place to fish, he seemed happy, even blithe. As we passed the carcass of a run-over deer with the white of buzzard droppings splattered all around, he said, “I’ve been fly-fishing since I was eight years old. Bird hunting, too. My grandfather sent me a fly rod and a 12-gauge shotgun for my eighth birthday, because he fished and hunted and wanted me to be like him. He was a Cajun from south Louisiana. His last name was Cherami. That was my mom’s family, and my dad’s family was also from the South, but they were more, like, aristocrats. My last name, Randolph, is an old Virginia name, and I’m actually a direct descendant of Thomas Jefferson. My dad’s father is buried at Monticello.”

We went down the riprap beside the tracks and held back the pricker bushes for each other. They were heavy with black raspberries; the smell in the cooler air by the water was like someone making jam. He stopped to look at the Deschutes before wading in. “This is the greatest river in America,” he said. “It’s the only one I know of that’s both a great steelhead river and a blue-ribbon trout stream. The way I came to it was, I was married to Florence Belmondo. Do you know who Jean-Paul Belmondo is? Famous French movie actor? You do? Cool! A lot of people never heard of him. Anyway, Florence is his daughter. She’s an amazing person, very sort of withdrawn in a group, but warm and up for anything—like, she has no fear—and knockout beautiful on top of that. We met on a blind date in Carmel, California, and were together from then on. Flo and I got married in 2003, and we did stuff like stay at Belmondo’s house in Paris and his compound in Antigua.”

I looked at Joe, both to make sure he was being serious and to reexamine his face. I observed that he looked a bit like Belmondo himself—the same close-set, soulful eyes, big ears, and wry, down-turned mouth.

Florence skis, Joe was a snowboarder. They began to visit central Oregon for the snow at Mount Bachelor, Joe discovered the Deschutes, Florence got him a guided trip on the river as a present, he fell in love with the river, they moved to Sisters, and she bought them a big house in town in 2005. “After I learned the river and started my own guiding, I think that was what created problems between Florence and me,” Joe said.

“Being a kept man sounds great, but it’s really not. To be honest, there were other problems, too. So finally we divorced. That was in ’08. We tried to get back together once or twice, but it didn’t work out. Well, anyway—man, it was awesome being married to her. I’ll always be grateful to her, because she’s the reason I came here and found this river. And I have no desire to fish anywhere else but on the Deschutes for the rest of my life.”

The railroad tracks we were walking on belong to the Burlington Northern and Santa Fe Railway. During the day, the trains sound their horns and rattle Maupin’s stop signs and bounce echoes around the canyon. At night they are quieter; if trains can be said to tiptoe, these do. The rhythmic sound of their wheels rises, fills your ears, and fades; the silence after it’s gone refills with the sound of the river. We were out in the night in Maupin a lot because first light and last light are good times to catch steelhead. It seems to me now that I spent as much time with Joe in the dark as I did in the light.

On my second night, he and I went to a fish hatchery downstream from town. We parked, zigzagged down a slope, passed dark buildings, crossed a lawn, and wrong-footed our way along the tracks, on whose curving rails the moon had laid a dull shine. After about a mile, we plunged through some alders and into the river and stood in the water for a long time waiting for dawn to start. This all felt a bit spooky and furtive to me.

My instinct, I later learned, was right. I had a fishing license, and Joe had licenses both to fish and to guide. He did not, however, possess a valid permit to be a fishing guide on the Deschutes. Two months earlier, he had left the Fly Fisher’s Place in Sisters (actually, he had been fired), and thus he had lost the guiding permit that the shop provided him. His attempt to jury-rig a permit from a rafting guide’s permit loaned to him by an outfitter in Maupin was not enough, because it allowed him to guide rafters but not anglers. Joe was breaking the law, in other words, and the consequences could be a fine of up to $2,500, a possible prison term, and the forfeit of his guiding license—no small risk to run.

On some evenings, after fishing, Joe and I went to Maupin’s bars. They were packed with a young crowd that included many rafting guides, and everybody seemed to know Joe. He sat drinking beers and watching two or more baseball games on the bar TVs while young guys came up to him, often asking for advice—“She’s kissed me twice, Joe, and I mean, she kissed me. But I haven’t even brought up anything about sex.” Joe: “Hell, tee her up, man, and ask questions later!” At the end of the night a barmaid announced last call, and Joe told her, “I’ll have another beer, and a cot.”

When Tiger Woods fished the Deschutes some years ago (with John Hazel, not with Joe), he did not pick up the spey cast right away, so I guess it’s no surprise that I didn’t, either. I simply couldn’t get the message, and I told Joe I wanted to go back to the fly rod. Not possible, he said. He had no fly rod; and, at his insistence, I had not brought mine. He was a patient and remorseless coach, smoking and commenting on each attempt as I tried over and over. “You fucked up, Bud. Your rod tip was almost in the water on that last one. Keep the tip high.” A failed spey cast is a shambles, like the collapse of a circus tent, with pole and line in chaos, and disgrace everywhere.

But he wouldn’t give up. I worried that it might be painful for him to watch something he did so beautifully being done so wrong, but now I think his depression gave him a sort of immunity. The tedium of watching me may have been nothing compared with what he was feeling inside. And when occasionally I did get it, his enthusiasm was gigantic: “That’s it! Money!” he would holler as the line sailed out.

So I'm in my motel cabin the night before our three-day float trip, and I can’t sleep. I keep practicing the motions of the cast—one, two, three, four—like the present-arms drill in a commercial for the Marine Corps on TV. I practice the cast when I’m pacing around the motel-cabin floor and when I’m lying on my back in the bed. Joe has told me that the first pool we will fish is the best pool on the entire lower river.

If I don’t catch a fish there, I figure, my chances for success will go way down. He has shown me how to cast from the right side of the river and from the left; you turn the motion around, like batting from opposite sides of the plate. He has said we will fish this first pool from the right side, so I practice that cast only. I keep remembering that I have never caught a steelhead. I do not sleep a wink.

He has told me to come to his house at 3:45 a.m. The early start is essential, he has assured me, because another guide is likely to be in the pool before us if we’re late. At 3:15

I put on my gear and drive to his house. All his windows are dark. The moon is up, and I wait in the shadow of Joe’s trailered driftboat. No sign of activity in the house. At the tick of 3:45, I step noisily onto the front porch in my studded wading shoes and rap on the door. Through the window I can see only darkness, and the corner of a white laundry basket in a patch of moonlight. I call Joe’s name. A pause. Then, from somewhere inside: “Th’damn alarm didn’t go off!”

He comes out, rumpled and sleepy, and puts on his waders, which were hanging on the porch rail. We get in the Tahoe and take off, stopping on the way to pick up some coffee and pastry from the free breakfast spread at a motel considerably more expensive than my own. Joe assures me this is OK; no one is around to disagree.

He has told me to come to his house at 3:45 a.m. The early start is essential, he has assured me. At 3:15 I put on my gear and drive to his house. At the tick of 3:45, I step noisily onto the front porch in my studded wading shoes and rap on the door. Then, from somewhere inside: “Th’damn alarm didn’t go off!”

We rattle for half an hour down a county road beside the river, leaving dust behind, and then pull into a location he asks me not to disclose. He backs the driftboat down to the river and launches it and we get in. At the second or third scrape of the oars against the boat’s aluminum sides, headlamps light up at a place not far from the boat launch. Guys are camped there so as to get to this pool at first light, and we have beaten them to it, Joe says with satisfaction. We go a short distance downstream and stop under the branches of trees on the right-hand bank.

The moon is not high enough to reach into the canyon, so the water is completely dark. We wait, not talking. I unwrap and eat the Heartland Bakery cinnamon Danish from the more expensive motel’s breakfast spread and crumple the wrapper and put it in the top of my waders and rinse my fingers in the river. The sky lightens and the water becomes a pewter color. Faintly, its ripples and current patterns can now be seen. Joe puts out his cigarette and applies ChapStick to his lips. We slide from the boat into the river.

My fear of wading has receded, thanks partly to my new wading staff. We go halfway across the pool. Joe tells me where to put the fly—a pattern called the Green Butt Skunk—and I begin to cast. Suddenly, I’m casting well and throwing line far across the river. Joe exclaims in astonishment and yells, “Money! Goddamn! You’re throwing line as good as Abe Streep!” (He is referring to an editor of this magazine, a fine athlete who fished with Joe the year before.) I am elated and try not to think about how I am managing to cast this well. I fish the fly across and downstream as the line swings in the current. I strip in the line, take a step downstream, and cast again.

Cast, step, cast again; I work my way down the pool, Joe next to me. We pause as a train goes by, hauling a collection of graffiti on the sides of its white boxcars. I notice a purple, bulbous scrawl that reminds me of something. Joe tells me to cast toward a pile of white driftwood on the bank. I send 50 or 60 feet of line straight at it, lay the fly beside it, swing the fly across. The light is now high enough that the ripples and the lanes of current are distinct. At the end of the swing, a swift, curved disturbance appears in the pewter surface of the river, and the line pulls powerfully tight.

Joe's father, William Randolph, was a navy pilot who flew many missions in Vietnam and could be gone for months at a time. Brenda, Joe’s mother, stayed home with Joe (called Joey), his older sister, Kay, and his younger sister, Fran. The family spent much of the kids’ childhood at Naval Air Station Lemoore, south of Fresno, California, where Joe often rode his bicycle down to the Kings River to fish.

Sometimes he hunted for ducks with family friends. Later he even had a scabbard on his bicycle in which he could carry his shotgun. His friends had shotguns, too, and sometimes they would stand about a hundred yards apart in a field and shoot at each other with the lighter sizes of birdshot. The pellets did not penetrate but “stung like crazy” when they hit. Once, when Joe was speeding along on his bicycle without a helmet, he came out from behind a dumpster and a passing garbage truck ran into him and knocked him unconscious. There was not much male supervision on the base with the dads away at war.

Joe’s mother had problems with depression, which the kids did not understand until they were in their twenties. Once or twice they went to stay with relatives while she was hospitalized. When Joe was in grade school, she and his father divorced. Joe’s main emotional problem, as Kay remembers, was getting angry, often at himself for personal frustrations. As a boy, he played tennis and traveled to tournaments and earned a national junior-level ranking. Being tall, he had a big serve, but his inability to avoid blowups on the court ruled out tennis for him. Other sports he excelled in were basketball, baseball, track, and volley-ball.

He went to high school in Fresno but did not graduate, although he did get his GED. To acquire a useful trade, in the late 1980s, he attended a school in the Midwest where he learned to be a baker; then he decided that was not for him and returned to California. He was kicked off the basketball team at Monterey Peninsula College for skipping practice to fish. Various injuries—elbow, knee, a severe fracture of the left ankle—interfered with his promising college baseball career. He once watched a doctor chip a bone spur off his knee with a chisel and did not pass out.

In his thirties, in Monterey, he tried to qualify for the semipro beach-volleyball circuit and took steroids to improve his game. The drugs caused him to feel invincible and aggressive and righteously angry, and added a foot to his vertical leap, but he did not make the roster. While playing volleyball he met a woman named Tricia, and they married. The couple had two children—Hank, born in 1995, and Maddi, born in 1997. He and Tricia separated in about 2000 and later divorced.

Now the sun had risen over the canyon, and Joe was navigating us through rapids whose splashes wet my notebook as I recorded the details of my first steelhead—a six-pound hatchery fish from far upstream, according to the identification made by Joe on the basis of the fish’s clipped maxillary fin (a tiny fin by the mouth).

“The tug is the drug,” steelheaders say, describing that first strike and the fight that follows. This was true, as I could now affirm. The afterglow was great, too. I looked up at the canyon walls rising like hallelujah arms, their brown grasses crossed by eagle shadows, and at the green patches where small springs came up, and the herd of bighorn sheep starting mini rockslides behind their back hooves, and the hatch of tiny crane flies like dust motes in the sunlight.

Happiness! The pressure was off, I had caught the fish, defeated the possible jinx, the article would now work out. In this mood, I could have fallen out of the boat and drowned and not minded, or not minded much. The morning had become hot, and Joe asked if I wanted some water. He opened the cooler. Inside I saw a few bottles of spring water and a 30-pack of Keystone beer in cans. Joe’s assistant for the trip, a young man named J. T. Barnes, went by in a yellow raft loaded with gear, and Joe waved. He said J.T. would set up our evening camp downstream.

Every fishing trip reconstructs a cosmogony, a world of angling defeats and victories, heroes and fools. Joe told me about a guy he fished with once who hooked a bat, and the guy laughed as the bat flew here and there at the end of his line, and then it flew directly at the guy’s head and wrapped the line around the guy’s neck and was in his face flapping and hissing and the guy fell on the ground screaming for Joe to get the bat off him and Joe couldn’t do a thing, he was laughing so hard.

“Do your clients ever hook you?” I asked.

“Oh, hell yes, all the time. Once I was standing on the bank and this guy was in the river fly-casting, and he wrapped his backcast around my neck, and I yelled at him, and what does the guy do but yank harder! Almost strangled me. I’ll never forget that fucking guy. We laughed about it later in camp.”

The next pool we fished happened to be on the left side. I had not practiced the left-side cast during my insomniac night. Now when I tried it I could not do it at all. The pool after that was on the right, but my flailing on the left had caused me to forget how to cast from the right. Again the circus-tent collapse, again chaos and disgrace. My euphoria wore off, to be replaced by symptoms of withdrawal.

I liked that Joe always called me “Bud.” It must have been his standard form of address for guys he was guiding. The word carried overtones of affection, familiarity, respect. He got a chance to use it a lot while trying to help me regain my cast, because I soon fell into a dire slump, flop sweat bursting on my forehead, all physical coordination gone.

“Bud, you want to turn your entire upper body toward the opposite bank as you sweep that line.… You’re trying to do it all with your arms, Bud.… Watch that line, Bud, you’re coming forward with it just a half-second too late.” I was ready to flip out, lose my temper, hurl the rod into the trees. Joe was all calmness, gesturing with the cigarette between two fingers of his right hand. “Try it again, Bud, you almost had it that time.”

By midafternoon Joe started in on the 30-pack of Keystone, but he took his time with it and showed no effects. Our camp that night was at a wide, flat place that had been an airfield. J.T. served shrimp appetizers and steak. Joe and I sat in camp chairs while he drank Keystone and told more stories—about his Cajun grandfather who used to drink and pass out on fishing excursions, and Joe had to rouse him so he wouldn’t trail his leg in the gator-infested waters; about a stripper he had a wild affair with, and how they happened to break up; about playing basketball at night on inner-city courts in Fresno where you put quarters in a meter to keep the playground lights on. At full dark, I went into my tent and looked through the mesh at the satellites going by. Joe stayed up and drank Keystone and watched sports on his iPhone.

I was back in the river and mangling my cast again the next morning while Joe and J.T. loaded the raft. Out of my hearing (as I learned afterward from J.T.), their conversation turned to J.T.’s father, who died when J.T. was 15. Joe asked J.T. a lot of questions about how the death had affected him.

J.T. misunderstood Joe’s instructions and set up our next camp at the wrong place, a narrow ledge at the foot of a sagebrush-covered slope. Joe was angry but didn’t yell at him. During dinner that evening, J.T. told us the story of his recent skateboarding injury, when he dislocated his right elbow and snapped all the tendons so the bones of his forearm and hand were hanging only by the skin. Joe watched a football game and talked about Robert Griffin III, who was destined to be one of the greatest quarterbacks of all time, in Joe’s opinion. As I went to bed I could still hear his iPhone’s signifying noises.

I saw a figure standing in the moonlight by the camp. Joe smiled and said, “You, too, Bud?” Now, looking back, I believe that what I saw was a ghost—an actual person who also happened to be a ghost, or who was contemplating being one.

At a very late hour, I awoke to total quiet and the sound of the river. The moon was pressing black shadows against the side of my tent. I got out of my sleeping bag and unzipped the tent flap and walked a distance away, for the usual middle-of-the-night purpose. When I turned to go back, I saw a figure standing in the moonlight by the camp. It was just standing there in the sagebrush and looking at me.

At first I could not distinguish the face, but as I got closer I saw that it was Joe. At least it ought to be, because he was the most likely possibility; but the figure just stood in silence, half-shadowed by sagebrush bushes up to the waist. I blinked to get the sleep out of my eyes. As I got closer, I saw it had to be Joe, unquestionably. Still no sound, no sign of recognition. I came closer still. Then Joe smiled and said, “You, too, Bud?” in a companionable tone. I felt a certain relief, even gratitude, at his ability to be wry about this odd moonlight encounter between two older guys getting up in the night. Now, looking back, I believe that more was going on. I believe that what I saw was a ghost—an actual person who also happened to be a ghost, or who was contemplating being one.

The poor guy. Here I was locked in petty torment over my cast, struggling inwardly with every coach I’d ever disappointed, and Joe was… who knows where? No place good. In fact, I knew very little about him. I didn’t know that he had started guiding for the Fly Fisher’s Place in 2009, that he’d done splendidly that year (the best in modern history for steelhead in the Deschutes), that he had suffered a depression in the fall after the season ended, that he’d been broke, that friends had found him work and loaned him money.

I didn’t know that after his next guiding season, in 2010, he had gone into an even worse depression; that on December 26, 2010, he had written a suicide note and swallowed pills and taped a plastic bag over his head in the back offices of the Fly Fisher’s Place; that he’d been interrupted in this attempt and rushed to a hospital in Bend; that afterward he had spent time in the psychiatric ward of the hospital; that his friends in Sisters and his boss, Jeff Perin, owner of the fly shop, had met with him regularly in the months following to help him recover.

I didn’t know that after the next season, in late 2011, he had disappeared; that Perin, fearing a repetition, had called the state police; and that they had searched for him along the Deschutes Valley with a small plane and a boat and eventually found him unharmed and returning home. Joe later told Perin he had indeed thought about killing himself during this episode but had decided not to.

I didn’t know that Perin had refrained from firing Joe on several occasions—for example, when Joe was guiding an older angler who happened to be a psychiatrist with the apt name of Dr. George Mecouch, along with one of Dr. Mecouch’s friends, and a repo man showed up with police officers and a flatbed, and they repossessed Joe’s truck (a previous one), leaving Joe and his elderly clients stranded by the side of the road in the middle of nowhere at eleven o’clock at night. Dr. Mecouch, evidently an equable and humorous fellow, had laughed about the experience, thereby perhaps saving Joe’s job. I did not know that Perin had permanently ended his professional relationship with Joe when Joe refused to guide on a busy Saturday in July of 2012 because he had received no tip from his clients of the day before.

The spot where Joe killed himself is out in the woods about six miles from Sisters. You drive on a rutted Forest Service road for the last mile or two until you get to a clearing with a large gravel pit and a smaller one beside it. Local people come here for target practice. Splintery, shot-up pieces of plywood lie on the ground, and at the nearer end the spent shotgun-shell casings resemble strewn confetti. Their colors are light blue, dark blue, pink, yellow, forest green, red, black, and purple. Small pools of muddy water occupy the centers of the gravel pits, and the gray, rutted earth holds a litter of broken clay-pigeon targets, some in high-visibility orange. At the clearing’s border, dark pine trees rise all around.

Probably to forestall the chance that he would be interrupted this time, Joe had told some friends that he was going to Spokane to look for work, others that he would be visiting his children in California. On November 4, 2012, he spent the afternoon at Bronco Billy’s, a restaurant-bar in Sisters, watching a football game and drinking Maker’s Mark with beer chasers. At about six in the evening he left, walking out on a bar tab of about $18. The bartender thought he had gone outside to take a phone call. At some time after that, he drove to the gravel pit, parked at its northwest edge, and ran a garden hose from the exhaust pipe to the right rear passenger-side window, sealing the gaps around the pipe and in the window with towels and clothes. A man who went to the gravel pit to shoot discovered the body on November 14. In two weeks, Joe would have been 49 years old.

He left no suicide note, but he did provide a couple of visual commentaries at the scene for those who could decode them. The garden hose he used came from the Fly Fisher’s Place. Joe stole it for this purpose, one can surmise, as a cry for help or gesture of anger directed at his former boss, Jeff Perin.

The spot where Joe killed himself is out in the woods about six miles from Sisters. He left no suicide note.

Over the summer, Joe’s weeks of illegal guiding had caught up with him when the state police presented him with a ticket for the violation. He would be required to go to court, and in all likelihood his local guiding career would be through, at least for a good while. Joe thought Perin had turned him in to the authorities; and, in fact, Perin and other guides had done exactly that. Joe was often aggressive and contentious on the river, he competed for clients, and his illegal status made people even more irate. But, in the end, to say that Joe’s legal difficulties were what undid him would be a stretch, given his history.

Joe’s friend Diane Daviscourt, when she visited the scene, found an empty Marlboro pack stuck in a brittlebrush bush next to where Joe had parked. The pack rested upright among the branches, where it could only have been put deliberately. She took it as a sign of his having given up on everything, and as his way of saying, “Don’t forget me.”

John Hazel, the Deschutes River’s senior guide, said Joe was a charismatic fellow who took fishing too seriously. “I used to tell him, ‘It’s only fishing, Joe.’ He got really down on himself when he didn’t catch fish. Most guides are arrogant—Joe possessed the opposite of that. Whoever he was guiding, he looked at the person and tried to figure out what that person wanted.” Daviscourt, who had briefly been Joe’s girlfriend, said he was her best friend, and made a much better friend than a boyfriend. “He fooled us all,” she said. “I haven’t picked up a fly-fishing rod since he died.”

She made a wooden cross for him and put it up next to where she found the Marlboro pack. The cross says Joe R. on it in black marker, and attached to it with pushpins is a laminated photo of Joe, completely happy, standing in the river with a steelhead in his hands and a spey rod by his feet. On the pine needles beside the cross is a bottle of Trumer Pils, the brand Joe drank when she was buying.

Just before Joe died, J. T. Barnes was calling him a lot, partly to say hi, and partly because Joe had never paid him for helping on the trip with me. (He did split the tip, however.) For someone now out $600, J.T. had only kind words for Joe. “He was like the ideal older brother. And he could be so up, so crazy enthusiastic, about ordinary stuff. One day we were packing his driftboat before a trip, drinking beer, and I told him that I play the banjo. Joe got this astonished, happy look on his face, and he said, ‘You play the banjo? No way! That is so great—I sing!’ That made me laugh, but he was totally being serious. I play the banjo, Joe sings!”

Joe had six dollars in his wallet when he died. Kay, his sister, who lives in Napa, thought Joe’s chronic lack of money was why he lost touch with his family. “Joe was always making bad decisions financially. Maybe, because he had a lot of pride, that made him never want to see us. But he was doing what he loved, supporting himself as a famous fishing guide. He had no idea how proud his family was of him.”

Alex Gonsiewski, a highly regarded young guide on the river, who works for John Hazel, said that Joe taught him most of what he knows. When Gonsiewski took his first try at running rapids that have drowned people, Joe was in the bow of the driftboat helping him through. “It’s tough to be the kind of person who lives for extreme things, like Joe was,” Gonsiewski said. “His eyes always looked sad. He loved this river more than anywhere. And better than anybody, he could dial you in on how to fish it. He showed me the river, and now every place on the river makes me think of him. He was an ordinary, everyday guy who was also amazing. I miss him every day.”

The paths along the river that have been made by anglers’ feet are well worn and wide. Many who come to fish the Deschutes are driven by a deep, almost desperate need. So much of the world is bullshit. This river is not. Among the many natural glories of the Northwest that have been lost, this valley—still mostly undeveloped, except for the train tracks—and its beautiful, tough fish have survived.

So much of the world is bullshit. This river is not. Among the many natural glories of the Northwest that have been lost, this valley—still mostly undeveloped, except for the train tracks—and its beautiful, tough fish have survived.

Joe was the nakedest angler I’ve ever known. He came to the river from a world of bullshit, interior and otherwise, and found here a place and a sport to which his own particular sensors were perfectly attuned. Every-thing was OK when he was on the river… except that then everything had to stay that way continuously, or else horrible feelings of withdrawal would creep in. For me the starkest sadness about Joe’s death was that the river and the steelhead weren’t enough.

At the end of my float trip with Joe, just before we reached the river’s mouth, he stopped at a nondescript, wide, shallow stretch with a turquoise-flowing groove. He said he called this spot Mariano, after Mariano Rivera, the Yankees’ great relief pitcher, because of all the trips it had saved. I stood and cast to the groove just as told to, and a sudden river quake bent the spey rod double. The ten-pound steelhead I landed after a long fight writhed like a constrictor when I tried to hold it for a photograph.

The next evening, not long before I left for the airport, Joe and I floated the river above Maupin a last time. Now he wasn’t my guide; he had me go first and fish a hundred yards or so ahead of him. Dusk deepened, and suddenly I was casting well again. I looked back at Joe, and he raised his fist in the air approvingly. At the end of his silhouetted arm, the glow of a cigarette could be seen. I rolled out one cast after the next. It’s hard to teach a longtime angler anything, but Joe had taught me. He knocked the rust off my fishing life and gave me a skill that brought back the delight of learning, like the day I first learned to ride a bicycle. I remembered that morning when we were floating downstream among the crane flies in the sunlight. Just to know it’s possible to be that happy is worth something, even if the feeling doesn’t last. Hanging out with Joe uncovered long-overgrown paths back to childhood. Peace to his soul.

Contributing editor Ian Frazier is the author most recently of The Cursing Mommy’s Book of Days.