One hundred miles is a long drive, an even longer bike ride, and for many, an unthinkable distance to run. Yet an increasing number of endurance athletes are taking on these longer ultramarathons. Ultrarunning.com estimates that 6,000 people raced 100 miles in 2013, leading Running Times to ask on the cover of a recent issue, “Is 100 miles the new marathon?”

But just because the distance is growing in popularity doesn’t mean it’s any less stressful on the human body. Even for the winningest runners, things tend to get pretty weird on the trail. Here, we explain exactly what’s going on in your body during a 100-mile run and, when possible, how to avoid the bad stuff.

Brain

The brain is the “most sensitive organ to heat damage,” says Matthew Laye, a physiologist who studies endurance athletes at the College of Idaho’s department of Health and Human Performance. (Laye is also an elite ultrarunner won last year’s Rocky Raccoon 100, his debut at that distance, in 13:17:42.) While heatstroke is quite rare—the brain generally prevents it by forcing the body to slow down—it can still be dangerous. Laye advises promoting cooling in hot conditions by packing ice around your neck and in your hat.

Less dangerous but more common are fantasies and hallucinations, which Laye believes result from general fatigue. To minimize the chances that your mind will play tricks on you, train in conditions that are “close to what you will experience in the race,” he says. For example, if you expect to be running through the night, start a few long training runs at 9 p.m. In the event you do start thinking—or worse, seeing—weird things, slow down and take a deep breath.

Even if your brain stays cool during a 100, you’ll inevitably experience something called central fatigue, which Laye describes as “a gradual decline in the nervous system’s ability to contract the muscles.” You might be able to prevent it by pairing cognitively challenging tasks with exercise while training. If you can’t manage Sudoku on the treadmill, however, consider scheduling a few hard training runs when you know you’ll already be mentally tired. Many successful ultrarunners intentionally head out on training runs at the end of a long, taxing day at the office.

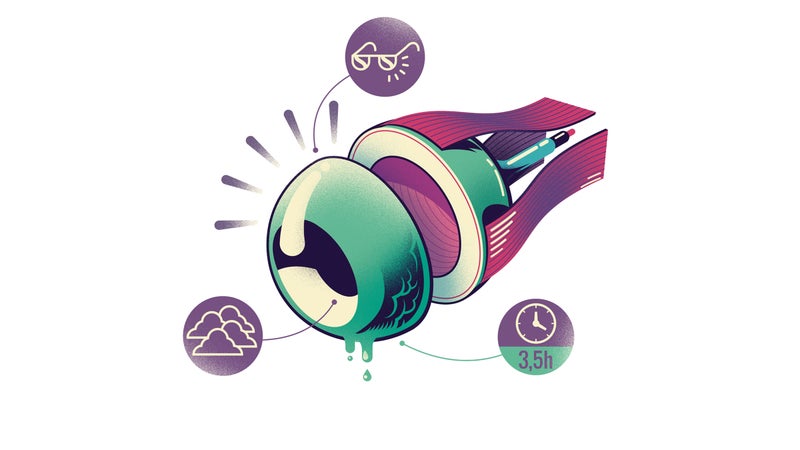

Eyes

Although very rare, according to a study in the journal Wilderness and Environmental Medicine, ultrarunners are susceptible to a “painless clouding of vision” that tends to occur beyond the 35-mile mark of some races. Researchers found that athletes who have had LASIK surgery are especially prone to in-competition optical irregularities. Fortunately, the authors note that these vision problems tend to resolve themselves within 3.5 hours of finishing.

While there is limited data on the causes of vision loss, Laye recommends wearing sunglasses, especially if you’ve had LASIK in the past. “The prevalence of these vision issues is far less in ultra-endurance athletes like cyclists or cross-country skiers who wear eye protection as a part of their sport.”

Mouth

Dehydration has long been a concern for endurance athletes. However, hyponatremia, a condition that results from drinking too much water and effectively diluting the sodium content of your blood, can actually be far more dangerous. Research in the Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology shows that substantial weight gain during exercise is the most useful predictor. “You think, ‘I need to elevate my sodium levels,’ so you pop a salt tab or high-sodium sports drink,” Laye says, “but that just makes you thirsty, so you end up drinking even more water, which further dilutes your blood.” If not addressed, the condition can lead to organ failure.

There’s been so much focus on and misunderstanding about dehydration that many athletes often overdrink when they should be worried about electrolyte balance instead. In reality, “mild dehydration is actually the norm during ultra-distance races, and it has no negative effects on performance or health,” says Laye. The best way to prevent hyponatremia is by drinking a well-balanced sports drink to thirst, explains Laye. Most commercial sports drinks, particularly those formulated for endurance athletes, contain between 120 and 190 milligrams of sodium per eight fluid ounces.

To really dial in your hydration needs, Doug MacLean, a running and triathlon coach with QT2 systems, suggests weighing yourself before and after a few long training runs (over three hours), during which you should drink and eat similarly to how you would on race day. Subtract the weight of whatever solid food you eat during the run from your post-run weight. If you’ve gained weight, you’re probably drinking too much. If you’ve lost more than 1 to 2 percent of your body weight, you’re not drinking enough.

Heart

As an ultra-distance race progresses, one of two things is likely to happen, says Larry Creswell, MD, a cardiac surgeon at the University of Mississippi and one of America’s most authoritative voices on the athlete’s ticker: Your heart rate will either increase or decrease. Each change is affected by the conditions at hand.

An increase in heart rate means the stroke volume, or the amount of blood pumped with each beat, may be declining, causing your heart to beat more frequently to push the same volume to the muscles. This is often caused by dehydration or hotter temperatures. A decrease in heart rate, on the other hand, is likely to occur if the muscular system becomes so fatigued that it no longer demands as much blood from the heart. Thus, a drop in heart rate almost always coincides with a drop in running speed. According to Creswell, appropriate pacing, hydration, and fueling all work to promote and prolong a steady heart rate.

Upon reaching the finish line, Creswell says it’s not uncommon for runners to become lightheaded, dizzy, and perhaps even collapse. This occurs so frequently that it has a name: exercise-associated collapse syndrome. Many races designate volunteers to catch finishers as they fall. Once you stop running, your heart rate drops, and your calves—which act like turkey basters, pumping blood through deep veins against gravity and back toward your heart—stop performing this task. Add a little dehydration, says Creswell, and you’ve got the perfect recipe for a drop in blood pressure that could cause lightheadedness and a subsequent fall. Creswell stresses that runners should be on the lookout for this and sit down at the first sign of dizziness.

As for whether long, slow exercise could cause long-term damage—an ongoing debate among exercise scientists—Creswell is suspect. “The heart is extremely well adapted to endurance exercise,” he says. “In long races like 100-milers, the heart is working at well below maximal levels, and to put things simply, it’s really good at doing that. As long as you’re well trained and healthy going into the race, I am hesitant to discourage this sort of endeavor.”

Stomach

GI issues are the most common reason runners drop out of 100-mile races, according to Kristin J. Stuempfle, a professor of health sciences at Gettysburg College in Pennsylvania. During a recent presentation at the Medicine and Science in Ultra-Endurance Sports conference, Stuempfle cited endotoximea—when molecules normally confined to the GI tract leak into the blood—as a likely cause of severe stomach problems.

Although the exact triggers of endotoximea are unknown, many experts speculate it is related to reduced blood flow to the gut. But Laye feels differently. He thinks endotoximea has more to do with the constant jostling of fluid and food caused by running. “You hardly, if ever, see endotoximea in cyclists,” he says, “and my hunch is that’s because cyclists are not bouncing up and down.”

Your best chance of thwarting GI problems during a race is to train your gut by practicing your fueling plan during training. Still, Laye says about 60 percent of competitors experience nausea at some point during an ultramarathon. If you do vomit, he says, “the only strategy is to keep eating and drinking. Aim to replenish what was lost ASAP.”

Arms

Arm fatigue can catch runners by surprise, but it is bound to happen, especially if you’re using a handheld water bottle or trekking poles.

Laye advises strengthening your arms during training by holding 2.5- to 5-pound weights and performing a natural running swing. Work in a few sets of 15 seconds on, 15 seconds off throughout the week. He also recommends long training runs using whatever gear you’ll have in the race. “What you don’t want to have happen,” warns Laye, “is for your arms to start hurting so much that you put down your water bottle. That’s a recipe for disaster.”

Legs

Running 100 miles is going to beat up your legs. There’s no way around it. The hours of pounding lead to accumulated damage of major muscles. In fact, studies show that it’s common for 100-mile finishers to have abnormal kidney values since they're working extra hard to filter residue of broken-down muscle from of the blood. Still, in 99 percent of cases, kidney values return to normal shortly after the race. However, seek medical attention immediately if your urine is cola-brown. Although extremely rare, a condition called rhabdomyolysis can occur when your kidneys are overwhelmed with particles from muscle breakdown and can cause permanent kidney damage.

To delay and minimize muscular damange in your legs, it is crucial to take in carbohydrates, which act as fuel for your muscles, explains Laye. He recommends shooting for 70 grams per hour. You want to start fueling immediately since you are burning through sugars at a faster rate than you can digest them. As Laye says, “It’s all about postponing depletion.”

Laye also recommends adding workouts that expose your leg muscles to the type of damage they’ll experience on race day. Running downhill is great for this. “Downhill-specific sessions were the single most important thing I did before Rocky Raccoon,” he says. “Even though the course was flat, those [downhill] sessions built up leg durability that delayed breakdown in the later stages of the race.”

Feet

Sweat, mud, river crossings, and pretty much everything else about running 100 miles contribute to foot friction. Most ultrarunners have issues with blisters.

According to Laye, applying an anti-chafe gel to problem spots—between your toes, along the sides of your feet, and on your heels—prior to racing is good first-line prevention. He also recommends wearing socks with individual toes for anyone prone to developing blisters between their toes.

To nip blisters in the bud during a race, Laye brings extra socks and an extra pair of shoes, often a different make than the ones he started with. This way, if he needs to change shoes, it’s less likely he’ll get the same hotspots. If you do get a blister during the race, Laye advises popping it with a sterile needle, draining it, taping it, and then putting on new socks.