Music fans everywhere were pleased to see the announcement last month that Kiss will finally make it into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, along with Cat Stevens, Hall and Oates, and producer Andrew Loog Oldham. The class of 2014 brings the total number of people inducted into the Hall to 719, a vaunted list that includes many performers but also at least a dozen producers, including heavyweights like George Martin, Quincy Jones, Phil Spector, and Jerry Wexler.

But there’s a key name that’s missing among them, and it is a travesty that the Hall has yet to acknowledge one of the most important producers of the fifties and sixties. Without this producer, Bob Dylan would not have broken through like he did—effectively bringing on the swinging sixties and changing music forever. Without this producer, Simon and Garfunkel might have quit before they ever got started, the Velvet Underground might have stayed underground, Frank Zappa might have spent his career recording on hapless independent labels, and jazz greats Sun Ra and Cecil Taylor would definitely have labored longer in obscurity than they already did. This producer helped them all find their voices and realize their visions, revolutionizing American music. He was a Harvard graduate. He was a Republican. He was a black guy from Waco, Texas.

Tom Wilson was born on March 25, 1931, and grew up in a mixed neighborhood just east of Baylor University. His mother, Fannie Odessa Brown Wilson, was a librarian, and his father, Thomas Blanchard Wilson, was a diligent insurance salesman who worked long hours and made enough money ($2,080 in 1940, well above the national average of $1,368) to keep them in the middle class.

Music was a constant presence in the Wilson family. They attended New Hope Baptist Church, the oldest black church in town, whose most famous member was Jules Bledsoe, who sang “Old Man River” on Broadway in 1927 and became the first black opera star. Wilson’s father directed one of New Hope’s three choirs, including leading a performance at a Texas Centennial celebration in 1936, when Tom Jr. was five. His grandfather owned a rug laundry, where he hosted Saturday afternoon jam sessions. Tom learned to play the trombone at segregated Moore High School.

After Wilson graduated from Moore, he moved to Nashville and spent a year at Fisk University before transferring to Harvard, where, according to writer Eric Olsen, who wrote the entry on Wilson in The Encyclopedia of Record Producers, he headed the Young Republican Club and officially studied economics. Unofficially, the handsome six-foot-four Wilson studied jazz, joining the Harvard New Jazz Society and working at the college radio station, WHRB, where he set up jam sessions and got more and more involved in the local jazz scene.

After graduating cum laude in 1954, he borrowed $900 and started his own label, Transition Records. It was a new era in jazz, and Wilson wanted to release some of the sounds he was hearing. One of his first signings was the pioneer bebop trumpeter Donald Byrd, whom he recorded with pianist Horace Silver and drummer Art Blakey. Wilson went to Chicago to record an album by avant-garde pianist and bandleader Sun Ra, who at that point had made only a couple of 45’s. Wilson also recorded 23-year-old post-bop pianist Cecil Taylor, putting out Jazz Advance, which The Penguin Guide to Jazz calls “one of the most extraordinary debuts in jazz.” Wilson—who by now was married with a couple of kids—wasn’t just a producer, he was a small businessman who took photographs, designed album covers, and wrote liner notes. He was DIY before DIY was cool.

In four years Wilson produced 22 albums (including an unreleased one featuring John Coltrane), but he ran into financial struggles and was forced to fold the label. He was offered a job as a jazz A&R (Artists and Repertoire) representative at United Artists in New York, the first in a series of similar jobs for other labels like Savoy Records and Audio Fidelity Records. He finally landed as a staff producer at Columbia Records in 1963, becoming the first African American to hold the position there.

His first significant job at Columbia was to finish an album by a young folk singer named Bob Dylan, who had done an album of mostly covers and was now halfway through a second album of mostly originals. Producers do a lot of different things. They take care of their artists, make them comfortable, push their buttons (it’s the engineer who actually twirls the knobs). Some producers, like Phil Spector, are heavy-handed auteurs, using musicians and singers to create something specific heard in their heads. Others are more like coaches, putting the right people together, setting the tone, making suggestions, giving encouragement, then getting out of the way. That was Wilson—a confident, genial man. “He was such an ebullient spirit,” remembered singer and songwriter Van Dyke Parks, whom Wilson signed around this time. “Charismatic, statuesque, and curiously empowering for those in his orbit.”

At first Wilson wasn’t thrilled with the prospect of working with someone like Dylan. “I didn’t even particularly like folk music,” he later told Melody Maker. “I’d been recording Sun Ra and John Coltrane, and I thought folk music was for the dumb guys. This guy played like the dumb guys. But then these words came out.” He told Albert Grossman, Dylan’s manager, that they should put a band behind him—“you might have a white Ray Charles”—but Dylan was comfortable doing things solo.

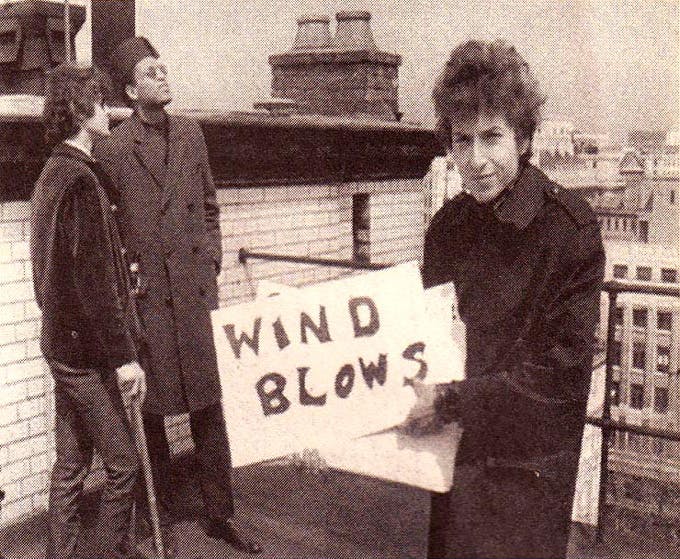

The scruffy 20-year-old clicked with the well-dressed 30-year-old, and they developed a good working relationship, doing two more acoustic albums (The Times They Are a-Changin’ and Another Side of Bob Dylan) before Wilson helped usher in the modern age in 1965 with Bringing It All Back Home, Dylan’s half-electric, half-acoustic tour de force. The year before, Wilson had overdubbed a band onto three of Dylan’s older songs, including “House of the Rising Sun,” but the sound didn’t work. On Bringing It All Back Home, Wilson got it right, bringing in a band of electric guitarists, a couple of bassists (including Bill Lee, director Spike Lee’s father), and a drummer. The result was Dylan’s first modern masterpiece, “Subterranean Homesick Blues,” whose frantic, lurching bluesy vibe would set the tone for the rest of the sixties. You can actually hear Wilson at the beginning of another song on the album, “Bob Dylan’s 115th Dream,” in which Dylan makes a false start, stops, starts laughing, and is joined by a laughing Wilson; after a few seconds you can hear Wilson say, “Wait a minute now. Okay, take two.” Then the band kicks in. As a listener, it sounds like you’ve been let in on a secret: Oh, so that’s the way they make records.

It was the beginning of a new Dylan—and a new era. Wilson would always say about Dylan going electric (as he did in a 1976 interview), “It came from me.” When Rolling Stone’s founder Jann Wenner interviewed Dylan in 1969 and asked him about Wilson’s claims to have brought Dylan to rock ’n’ roll, Dylan laughed but added, “He did to a certain extent. That is true. He did. He had a sound in mind.”

Wilson only did one more song with Dylan, and it was his biggest hit ever: “Like a Rolling Stone,” considered the number one rock song of all time by Rolling Stone magazine. Again Wilson recruited the band, and also invited a friend of his, Al Kooper, to watch. At some point, Kooper, a guitar player, slipped behind the organ during recording and began to play a simple line, ultimately giving the song its signature riff. At the start of one of the alternate takes, you can hear Wilson say, “Okay, Bob, we got everybody here, let’s do one.” This sums up Wilson’s production style: bring people together, get them ready, and let it rip.

Wilson signed or produced others at Columbia, including Tim Hardin, Pete Seeger, and Dion. His biggest hit, though, came in a bizarre, roundabout fashion when he recorded a young duo called Simon and Garfunkel. At first the result was a mopey acoustic album called Wednesday Morning 3 AM that sold terribly. Garfunkel went back to school while Simon moved to England. But in the meantime, a song from the album, “The Sounds of Silence,” was receiving airplay in Florida and Boston, and Wilson sensed an opportunity. He knew what a good rock band could do to a song and brought in some musicians—including a couple he had used to back up Dylan—to do overdubs. Columbia released the new version as a single—and it became a hit, climbing to number one by the end of 1965. Simon and Garfunkel reunited, folk rock was born, and Wilson was now a kingmaker.

In early 1966 Wilson left Columbia and took a job as head of A&R at Verve/MGM records. One of the first groups he signed was the Mothers of Invention, a gang of weirdos led by Frank Zappa who were fusing blues and psychedelia, jazz and noise, rock and the absurd into something altogether new. Wilson liked their sound so much that he demanded $21,000 from the label to make Freak Out!, the band’s first album (which was actually two LPs), a staggering sum in the mid-sixties. “Tom Wilson was a great guy,” Zappa later said. “He had vision, you know? And he really stood by us.” Wilson wound up producing their second album too.

Around this time he was also trying to figure out how to sign the Velvet Underground. He’d seen them play in a New York club and liked their provocative mix of melody and noise. He had even talked with band members Lou Reed and John Cale about recording for Columbia a year before. Wilson convinced the band to sign to Verve, because, in guitarist Sterling Morrison’s words, he said that “at Verve we could do anything we wanted. And he was right.” The band had already recorded most of its debut album, The Velvet Underground and Nico, and after signing with Wilson, MGM gave band members money to re-record three songs, including “Waiting for the Man,” “Heroin,” and “Venus in Furs.” In addition, Wilson took them into the studio and recorded the album’s sublime opener, “Sunday Morning.” Wilson was in the studio for the entirety of the band’s second album, the chaotic masterpiece White Light/White Heat, in 1967, where he sat back and let the band do what it did best. John Cale later said to the authors of Up-Tight: The Velvet Underground Story, “The band never again had as good a producer as Tom Wilson.”

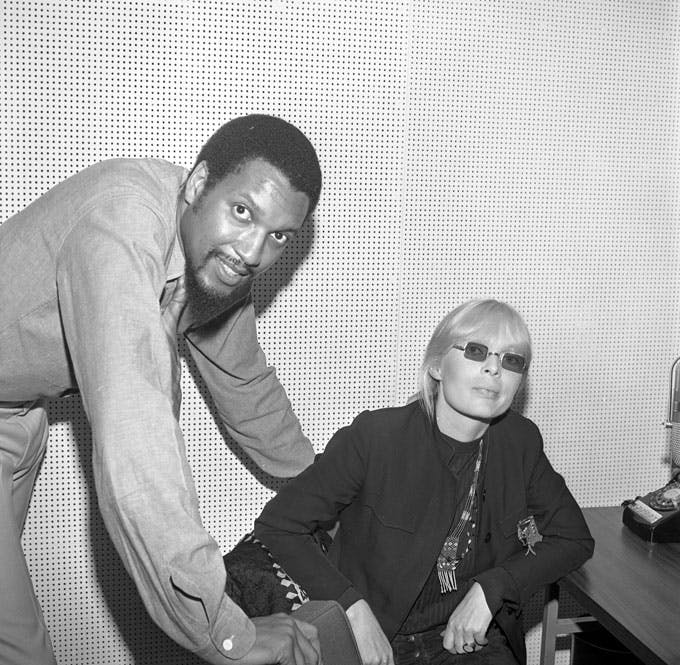

While he was at MGM, Wilson also produced Hugh Masekela, the Animals (“Sky Pilot”), the Blues Project, and the first album by psychedelic prog-rock pioneers Soft Machine. He helmed Nico’s first solo album, Chelsea Girl, writing flute arrangements* and bringing in guests like Reed and Jackson Browne. In 1967 Wilson had eight albums in the Top 100 but was active outside the studio too. In 1968 he hosted a radio show called “The Music Factory” that was syndicated to college radio stations. He also helped found the Record Plant, a modern 12-track recording studio in Manhattan.

At the start of 1968 Wilson left MGM and started his own Brooklyn-based production company and talent agency, the Tom Wilson Organization. By then he was one of the most successful producers in America, making $100,000 a year. He had two publishing companies, Terrible Tunes and Maudlin Melodies. He was producing two acts a month, young bands like the Bagatelle (soul rock from Boston), the Central Nervous System (psychedelic rock from Nova Scotia), and the Fraternity of Man (country rock from California; the group had a hit on the Easy Rider sound track with “Don’t Bogart Me”—a.k.a. “Don’t Bogart That Joint, My Friend”).

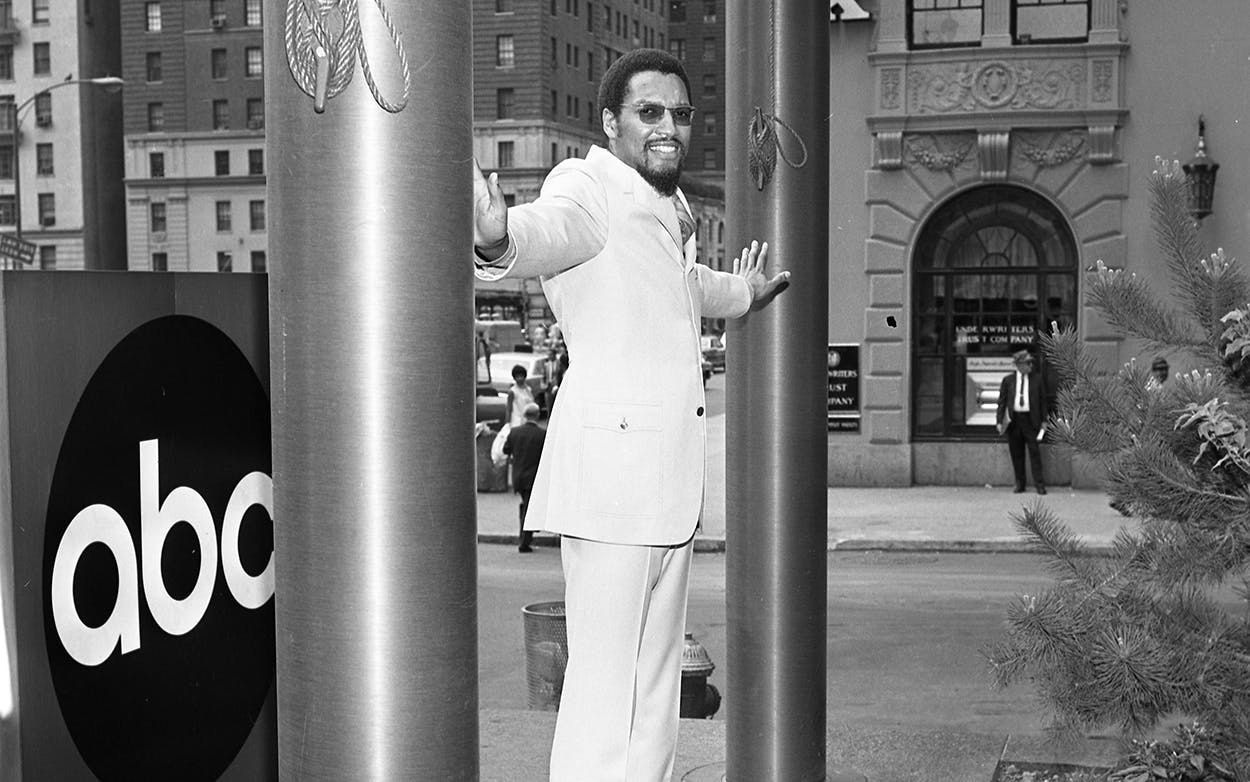

Later that year the New York Times Magazine did a long cover story on Wilson called “A Record Producer Is a Psychoanalyst With Rhythm.” The story called him “an exotic man in an exotic field” and noted his sartorial splendor. “Wilson strolls in wearing his work-a-day special: antelope suede jacket, lightweight white candy twill bell-bottom trousers, purple crepe shirt.” The writer, Ann Geracimos, noted that Wilson drove a blue 1960 Aston Martin sports car and that his apartment had “magenta walls, blueprint paper on the ceiling, fur carpeting and a vermilion lacquer bed, green-felt walls and German helmet lamps. He goes after change and sensation, almost by instinct, as though experience was always its own reward.” Wilson wasn’t into jazz anymore, Geracimos said; it was, in his mind, dead. Rock was the new jazz, the music that soaked up everything around it, and Wilson was the guy with the sponge.

And yet, as the sixties ended, Wilson seems to have lost his mojo. The hits stopped and soon the bands stopped coming to him. According to the discography compiled by journalist and music historian Irwin Chusid, Wilson produced only a handful of groups in the first years of the seventies, then found himself mostly co-producing and mixing for the remainder. He spent a lot of time in England, where he was working in other areas of the music business. A 1976 Melody Maker story noted that Wilson and his business partner, producer Larry Fallon, were working with Danny Sims, the manager of singer Johnny Nash. Wilson and Fallon had written an R&B opera called Mind Flyers of Gondwana that (the writer said) “weaves together the legend of Atlantis and the story of the black man in America from his roots in Africa.” It was to star Nash, Gladys Knight, Gil Scott-Heron, and the Righteous Brothers.

But the opera was not to be, nor was anything else. On September 6, 1978, Wilson died of a heart attack in Los Angeles. He was only 47.

What happened in his last decade? We don’t know. Geracimos wrote, “The pressures of the profession evidently lead him to seek diversion in a number of unorthodox ways.” What did that mean? Taking drugs? Writing fan letters to Richard Nixon? Perhaps this merely referred to Wilson’s status as a resolute ladies’ man (several musicians later told of how he spent much of his time in the studio on the phone talking to women; Cale would say, “Tom Wilson had this parade of beautiful girls coming through all the time”). Geracimos also wrote, “The private, darker side of Wilson (as he might refer to it, feeling, as he does, that he is composed of at least two separate personalities) is as consistent as a boomerang.” Did he get fed up with the spoiled rock ’n’ roll kids he was mentoring? Did he feel left behind by the very era he had helped foster? Wilson had never aligned himself with any of the radical changes going on around him, including the black power movement. A girlfriend of his from those days later told writer Eric Olsen, “Tom felt let down by blacks. He felt that after the civil rights successes of the fifties and sixties, blacks should stop complaining and get on with it. He felt they caused many of their own problems by carrying such large chips on their shoulders.”

Wilson was such an enigma—a conservative in a liberal time, a black man producing white artists whose songs were often at the forefront of the new age. The times they were a-changin’, and maybe Wilson felt out of step with them. By all accounts he didn’t care about the expectations of others. “He lived his life unapologetically as a human being,” said his friend Wally Amos (founder of Famous Amos cookies), “not as a black man.” Chusid has put up a comprehensive web site devoted to Wilson (http://www.producertomwilson.com/) and notes that it’s important to put the man’s Republican politics in context. “Historically, Democrats were the party of Jim Crow,” Chusid says. “The GOP stood for free enterprise, individual liberty, less government, and personal responsibility. Wilson had an honors degree in economics from Harvard. He was an entrepreneur. He didn’t want a handout, and didn’t claim victimhood because his skin was black. He felt the keys to success for all, regardless of race, were discipline and hard work. He was a Booker T. Washington kind of guy.”

Today, just as Tom Wilson gets no respect in Cleveland, home of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, he gets none in Waco, his hometown. Few know his name there, and even his gravestone, in Doris Miller Memorial Park, has the wrong year of his death. For some reason, it says 1975.

Much of Wilson’s life is a mystery—especially the beginning. How did a boy raised in Jim Crow–era Waco become one of the great music men of the twentieth century? How did he cultivate such an ear for talent? His end is a riddle too. What happened to Wilson in his final years?

What we do know is this: for a good chunk of time in between his beginning and his end, especially from 1955 to 1968, Tom Wilson made history. Modern music wouldn’t be the same without him, and, a word to the Hall, he deserves to be honored for that.

*Correction: A previous version of this story said Wilson wrote string arrangements on Chelsea Girl. He did not; his business partner Larry Fallon did. We regret the error.

- More About:

- Music

- Music Business