Feet Lost and Found in the Pacific Northwest

When feet started floating into the dark, coastal bays of British Columbia, it wasn’t hard to imagine the worst, especially when the Mounties went silent. Even paradise has an underbelly.

Heading out the door? Read this article on the Outside app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

When you're dealing with a tale of intrigue and suspicion in which nothing wants to be what it seems, the best place to start is at the beginning, before everything about the Mystery of the Feet got complicated. Before the dogged reporter and her theory of the Smiley Face Killers. Before the funeral feast of the submerged pig and the ravenous lobsters. And way before my afternoon with a knife-wielding man named Mountain Mike. Before all this, there is only the bucolic image of a little girl on a beach, looking for shells.

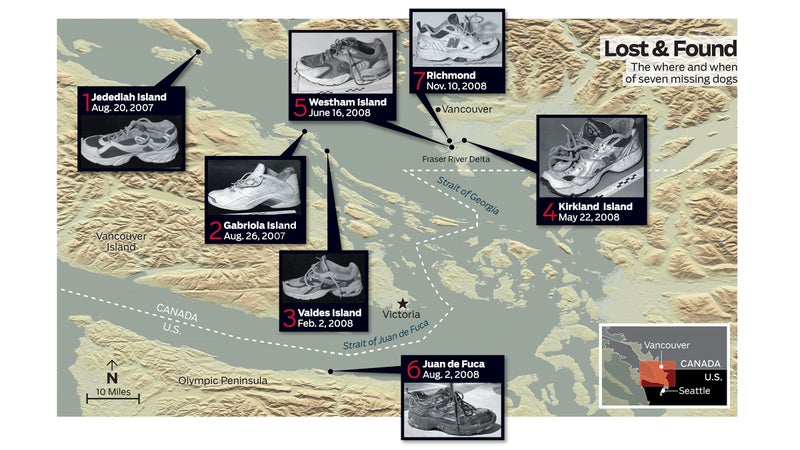

It's August 20, 2007. The girl and her family are on a sailing trip in British Columbia. They toss anchor at uninhabited Jedediah Island, 50 miles northwest of Vancouver. It's high summer, but the day is moody with drizzle, the cedars dark and foreboding above the pretty curl of cove.

The girl finds four sneakers on the sand. She lines them up, chooses one. It's a Campus-brand shoe, a righty, white with blue mesh, size 12. She unties the laces, tugging at a sandy sock within.

And, right then, out plops the Start of Everything. Because inside the sock is a human foot. Over the next 15 months, six more feet, also clad in socks and sneakers, will wash ashore at six different places on the puzzle of islands in the Georgia Strait, between Vancouver and Vancouver Island, and in the nearby Fraser River delta.

At first the feet are all men's feet, all right feet. Then a woman's foot appears. Then a left foot. Four of the feet match: one pair of women's feet, one pair of men's. That's seven feet, bow-tied in seaweed, that were once attached to a total of five bodies bodies that don't turn up.

The media arrive by helicopter and boat and do what the media do best: go apeshit. Reporters deliver fevered sound bites and write punny headlines (“Investigators Seek Leg-Up in Mystery Feet Case”), and for a few news cycles in early 2008, the whole world widens its eyes and scratches its head. Even the United News of Bangladesh clucks at the odd and tragic goings-on up there in British Columbia.

In Vancouver, at the HQ of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, the authorities know little and say less, and they do it in that grumpy, pinch-lipped way that makes people wonder what they aren't being told. In November 2008, Corporal Annie Linteau, a Mountie spokeswoman, tells me over the phone that they aren't even close to coming up with an explanation. But that, she says, is mainly because there's no reason to think anything fishy is going on.

Seriously? Yes, Linteau says, pointing out that there were no saw marks on the bones, no evidence of foul play. Without that, what do seven feet amount to, really, other than ghoulish serendipity?

By the time I head out from New York for a personal look-see, in early 2009, detectives haven't solved the mystery, but they haven't given up. The Major Crimes Unit is trying to put names to the feet by tracking down DNA from relatives of 57 high-probability men on B.C.'s missing-persons rolls. (At press time, only one foot, the first, had been identified: It belonged to a missing man whom the authorities won't name, in deference to his family.) But even this gumshoe work might not crack the case. As Corporal Linteau tells me when we meet in person inside a windowless briefing room, where she flips through pictures of empty shoes set against rulers, like grim flash cards the search is limited to people known to be unaccounted for.

And so, as I head for the water-licked fringes of Greater Vancouver, the mystery is still as open-ended as a drinking straw.

No Reception

One foot on a beach might've only made a splash in the local Alberni Valley Times. But six days after the first foot was found, on a Sunday afternoon in late August 2007, Vancouver couple George Baugh and his wife, Michèle Géris, went hiking on Gabriola Island, about 40 miles south of Jedediah Island and across the Georgia Strait from Vancouver.

“We were on a trail that obviously hadn't been used for a while ferns were all grown up over it,” George is telling me. It's February, and we're sitting inside a café in downtown Vancouver. He says he and Michèle were walking single file, Michèle in the lead, when suddenly she stopped and said, “Look, there's a foot.”

This is why I especially wanted to talk to George and Michèle. It's not just that they found a foot (though that helps); it's that, in all the newspaper accounts, the couple seemed so sensible. And that's what a story about severed feet cries out for, isn't it? Grounding? Credibility?

George is a slim, 52-year-old wine importer whose entire presence whispers Canadian civility. He's wearing a forest-green turtleneck and a tight, gray-flecked Caesar haircut. When Michèle came across the shoe, a Reebok runner sitting a couple of yards off the trail at the base of a madrona tree, they both kept walking at first. It was just a sneaker in the woods, after all; maybe it had been carried up from the beach by a dog. But then they went back, because something bothered them about that shoe. It looked so…full.

George poked it with Michèle's hiking stick. He saw “something white, not dried out at all, sort of greasy-looking” nesting inside a fringe of frayed white sock. He called 911: no reception. Michèle suggested that they knock on the doors of homes near the path homes that just happened to be sitting on an isolated country lane called Stalker Road.

George: “I said, 'No, we're not going to knock at any houses. These guys could be involved.'”

Now, here in the café, he's talking, with characteristic thoughtfulness, about how humans crave patterns. It's how we make sense of things, he says. That day on Gabriola, as they sat waiting for the Mounties to arrive, he pulled a newspaper out of a rural mailbox. “Then we read about the Jedediah foot, which was the first one,” he says. “I thought, I think we've found the other foot! We've solved the mystery.”

But the mystery was just getting started. In February 2008, workers clearing brush on Valdes Island, just south of Gabriola, found Foot Number Three. It was another righty! Another runner! Another size 12! (Well, actually, size 11. But…close enough!)

And this well, this was when things sorta went nuts.

Northwest Noir

Oddity breeds speculation. Deny the people a quick answer to strange doings and they'll gladly make up a story to fill in the gaps.

They're victims of the 2004 Asian tsunami.

They're part of the rising body count in VanCity's mushrooming war of gangbangers.

Somewhere in there was the mouse peep of another story, perhaps a truer story that these were just distraught people who took a long walk off a short pier, or the unfound victims of some half-forgotten plane crash. Conspiracy abhors a vacuum.

And, of course, there was always that other possibility.

A couple of years ago, a sociologist named James DeFronzo ran the numbers. The northwestern United States, he found, has more serial killers per capita than anywhere else in the nation.

Argue the reason, but this land of Most Livable Cities Portland! Seattle! breeds killers the way Texas sires halfbacks. The Want-Ad Killer. The Box Car Killer. Ted Bundy. The Green River Killer, who likely murdered more than 48 women around Seattle in the eighties and nineties before getting nabbed in 2001. Long before that, in the 1910s, there was Dr. Linda Hazzard, in Olalla, Washington, whose cure for patients consisted of frequent enemas and a few teaspoons of asparagus broth a day. She killed at least 40 people at her “sanitarium,” Wilderness Heights. The locals called it Starvation Heights.

Like the apple maggot and American Idol, some unfortunate things don't stop at the border. Perhaps you've heard of Robert Pickton, B.C.'s shame? For several years, starting in the nineties, he brought prostitutes from Vancouver's heroin-plagued Downtown East side to his pig farm outside the city. There, he threw wild parties at his Piggy Palace Good Times Society and killed perhaps 49 women, grinding some of them up to feed the pigs and serving pork chops to visitors. Before Pickton, there was the “Boozing Barber,” Gilbert Paul Jordan, who killed at least seven Vancouver prostitutes. Farther north, between Prince Rupert and Prince George, as many as 19 women are missing along the so-called Highway of Tears.

There's a reason The X-Files was filmed in Vancouver and not Phoenix. Call it Northwest noir. It has its own hallmarks: winter's sooty, daylong dusk; the look of neon bleeding into the gutters; the way people sometimes head into the mountains and simply disappear. For all its deep-green beauty, the Northwest has more than enough mist and mystery to give a body chicken-skin.

So, for people up here, when three feet appeared, it wasn't much of a leap to imagine the worst. The Reebok Ripper? Sure, why not? After all, as the poet said, we have been acquainted with the night.

Savage Road, No Exit

The feet kept coming in 2008. After Foot Three was found in February, Four, a woman's New Balance, washed up in May, just south of Vancouver on Kirkland Island, in the Fraser River delta. In June, Five came ashore downstream, on the rural farming enclave of Westham Island, at the dock of married fishermen Mike and Sharon Bennett. Was the tide sweeping the feet upriver from the same spot? I wondered. What could savvy watermen like the Bennetts tell me?

Driving out to Westham Island in midwinter makes you think of that Annie Dillard line about the Northwest: “It was not quite raining, but everything was wet.” Moss on roofs. Ducks floating in drowned berry fields. All this can put you in a dark and darty-eyed state of mind if you're on an errand to talk about severed feet. It doesn't help that the sign guiding me to the water's edge reads SAVAGE ROAD (NO EXIT).

When I first called Mike, he'd said, “It's sure been an odd one around here, because I know two of the other people who found feet. Now that's weird, eh?” Yes, I agreed, that was weird. Obviously, we had a shared sensibility; he told me to drop on by when I got to town.

Now Mike is walking into his kitchen from outside, where he's been readying the family herring boat for the season. He's a strong-looking guy, buzz-cut. Out of the gate, he'd like to share some thoughts about the Mounties' working theory that all these feet are a coincidence, just so much cosmic buckshot. “They're trying to make it look like a freak random thing,” he says. “But that's just complete bullshit.”

So what's his take? “I would say they all came from up the river,” he says. “In fact, I'm sure of it. We found ours during the freshet time of year.” The freshet, he explains, is when the spring snowmelt down the Fraser is so big that nothing gets upriver by wind or tide.

“This is one of the great rivers of the world,” Mike continues, proud to live on its banks. After coursing nearly 900 miles through the Rockies and the Cariboos and the Coast Range, B.C.'s longest river ends here in a spraddle of channels and rich black mud, but not before it drains a Utah-size piece of provincial real estate. O Fraser, Drainpipe of the Canadian West! That foot could've come from anywhere! (Except downstream, is Mike's point.)

Mike and Sharon's foot showed up on June 16, 2008. “It was in the morning,” he recalls, “coffee time.” On a gorgeous late-spring day, they took their joe and headed out to see a friend whose boat was tied up at the end of their dock. As they walked out, they saw a runner floating sole side up. “There's a sneaker for you,” Sharon joked. “That's not good,” Mike replied, sounding serious. “It's a low floater.”

“We had a friend who drowned a few years ago, on the Fraser. And that was the first thing we thought of when we found it. That it was him.”

This one was inside a Nike, size 11, the first lefty. Eventually police would match it up with Foot Three.

Long after it was bagged and tagged, the foot kept bothering Mike and Sharon. “The sock was in perfect shape,” Mike says. “And…ah!” he adds, as if he nearly forgot, “the shoe had what appeared to be a bloodstain on the tongue.”

Wait a bloodstain? The police never mentioned a bloodstain. Mike gives me this look, like, Now you know.

Everybody I talk to has a pet solution to the feet mystery, but Mike offers one I haven't heard yet: the Container Theory. “My thought was, if somebody killed a bunch of guys and put their bodies in a container, and after a couple of years the container popped open, the shoes would be the only thing that came up.”

He adds, “It could be a car gone over a bank, when I said 'a container.'”

“So it's not necessarily nefarious?”

“But remember the blood on the tongue,” he says, chiding me.

Bloody footwear, “containers” stuffed with bodies my head is spinning. Sharon agrees to walk me down to where they found the foot. By the water, a skiff dangles from a winch. A gull cries overhead. Sharon stands on the dock and jabs a cigarette at the green, glassy water. Back at the house, she told me that finding the foot had left her with an ugly feeling. “I cried a little bit,” she said. “And after I lifted the foot, I couldn't wash my hand enough.”

Now, standing here, I feel foolish and selfish. What did I expect to gain by making her walk down to the dock? Behind us, the late-afternoon sky is exploding, pink cotton-candy clouds edged with gold adrift on the mirrored water. It's ridiculously peaceful.

Sharon says, “We had a friend who drowned a few years ago, on the Fraser. And that was the first thing we thought of when we found it. That it was him.”

And suddenly I understand: Crying is an entirely appropriate reaction to finding a foot floating outside your peaceful island home.

When Twenty Two Vanished

The Big Picture. That's what this tale lacks. Context. Perspective. A frame, to show how the puzzle pieces fit together. But the police won't or can't say much about it. Who else knows the shape of things?

Nobody writes as often or as well about missing British Columbians as Sandra, a pleasant bulldog of a reporter for the twice-a-week, 140,000-circulation Vancouver Courier. Sandra is 50, a heavy-breasted woman with a recent islands tan and red nails as perfect as Chiclets. When I drop by her house, she admits that, for a while, she didn't think much about the feet. She remembers the day she started to care, though. “It was after Bryan Braumberger went missing. It will be two years this June.”

On the evening of June 1, 2007, Braumberger, a 17-year-old from the Vancouver suburb of Burnaby, left a friend's house. His car was found not far from his home the next day, unlocked, lights on. “He just vanished,” says Sandra.

A few months later, around the time the first foot turned up, a young guy named John Kahler disappeared. Then Derek Kelly. Then Kellen McElwee. “It was after Kellen went missing in March that I really started to think,” Sandra says. Her research led to a shocking discovery: Not just a few but dozens of men had gone missing in southwestern B.C. in the previous four years. Even if you took away the ones who had any reason at all to disappear the tweakers, the drug mules, the psychically ravaged you still had, Sandra wrote, “22 healthy, apparently happy men from southwestern B.C. who have simply vanished.”

No way, you're thinking. This is Vancouver. Olympic City! And you'd be right, up to a point. From some angles, the place really is Emerald City, with its green-glass high-rises ringed by mountains that wear a geisha face of fresh powder, the air smelling of all good things earth and mountains and salt water. But shift your gaze a little, or pick up a newspaper, and your perspective changes. You read about seven young people shot in the past six days. You see the shuffling knots of junkies and whores at Hastings and Main. You find out that young men are vanishing like cigarette smoke. Even paradise has its underbelly.

The day after Sandra's first story came out, a foot was found. And again on June 16, after she was on the radio discussing the missing men, another foot washed up.

And it's not just Vancouver. All of B.C. has a missing-persons problem. Since 1950, more than one in five people who've gone missing in Canada have disappeared here, even though the province is home to just 13 percent of the population. That adds up to more than 2,400 people gone as of August 2009. By rough comparison, Kentucky, with the same population, is looking for 515.

For decades, you could rightly blame it on B.C.'s role as North America's breakwater. Charlie was last seen hauling in his nets? OK, sad, but at least we know how he died. Yet today hardly anybody disappears by falling off his Chris-Craft. Other things are making them go away and in much greater numbers during this decade than ever before. Nobody knows why.

Back at Sandra's dining-room table, I'm feeling dizzy. Again. Every puzzle piece I pick up fractures into smaller pieces. Through the sliding glass door, I can see her backyard, and above that the sky, which is white, or maybe smudged with the first bits of a front a sky waiting for color.

“But where do the feet fit in, Sandra?” I ask.

She smooths the newspaper stories on the table and says that, once she began writing about the missing men, “I start wondering if there's a connection between the three of them the feet, the missing men, and the Smiley Face Killers.”

According to two former NYPD detectives, Kevin Gannon and Anthony Duarte, there's a loose-knit gang of murderers at work across North America. They've killed 35 or more healthy, college-age men over the past decade or so, and they've gotten away with it by making the deaths look like drowning accidents. Graffiti'd smiley faces have been found at the alleged crime scenes.

Or so the detectives claim. Most law-enforcement officials aren't convinced. There's simply not much evidence that these deaths are attributable to anything but the sad confluence of young men, booze, and deep water. Still, Duarte and Gannon have hawked their theory on outlets from the Today show to CNN, and Sandra has pondered in the Courier whether the Smiley Face Killers have anything to do with the feet or with Vancouver's missing men. So far, the feet don't match any of the absent locals, and the Mounties are dismissive. But Sandra's point is, Who knows?

She raps a nail on the table. “The day after my first story came out,” she says, “a foot was found near the Massey Tunnel. And again on June 16, after I was on the radio discussing the missing men, another foot washed up.”

Wait, is she saying there was a message from the killer?

“I'm sure it's coincidental,” she says. “But, still, it's creepy.”

Footloose Beach

Many statistical problems have one piece of data that doesn't seem to fit. For B.C. police, it was a black Everest hiking shoe that washed up almost exactly one year after the first foot appeared. The trouble with Foot Six? It was found on Washington State's Olympic Peninsula, a good 100 miles southwest of Vancouver, on the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Could it be related? Was a copycat at work?

On the scene that foggy afternoon was Detective Sergeant Lyman Moores, of the Clallam County sheriff's office, who just now is steering his black Ford Excursion toward the beach where the foot was discovered. If there's a dress code somewhere for middle-aged detectives, Moores got the memo. He has the bald crown, the mustache, the thick-soled black loafers. A Styrofoam cup of bad filling-station coffee balances on a knee of his prune-colored wash-and-wear pants. With his non-steering hand, he gestures his way through an overview of what he and his detectives have learned about that shoe.

Only 252 size 11's of that model were made, Moores says. “They were all sold in Canada.”

A-ha! So the foot came from Canada! I mean, it had to. Right?

Well, maybe. But it could have been bought there and worn down here. Moores knows he needs more evidence before reaching any conclusion.

He pulls over at the rusting gate of an old seaside camp, the Silver King Resort, and we follow the seashore smell of clams to a small bay lined with skipping stones. By the steps to the water, some wit has written FOOTLOOSE BEACH on a piece of driftwood. Not 50 yards away, Moores points out where he found the foot. He toes a thick mulch of tide wrack with a black loafer.

“The wind'll often come from the north, and this is what happens,” he says. “The day we found the shoe, the wind had been blowing real hard from the north. There's no doubt in my mind that what's out in the strait is gonna wash up here.” So, given this, he says, maybe the foot did come from up in Canada.

That all makes sense, but I ask Moores a slightly broader question: What the hell is going on?

He answers with a detective's caution. “My mind's wide-open that it could be a combination of things,” he says. “Did a plane crash that we don't know about? Was this something related to a sports team? Because they were all wearing athletic shoes…”

A cop doesn't become a detective without being good at what he does, which means being suspicious. “I can't help thinking, being a cop, that someone's trying to dispose of bodies,” he says. “I remember a few years ago, there was a mortician down south who was burying them in his backyard.” And what about that other guy, who was supposed to be burying people's cremated ashes at sea but instead stacked them in a storage locker?

Yeah, what about those guys? Surely they could have imitators?

“It's just too much of a coincidence,” Moores says, squinting out toward the strait, where Canada lurks in the mist.

The Knife-Wielding Stranger

Water is the common denominator to this mystery. Water embraces these islands. It carried the feet to shore. I've got to get closer to the water to get closer to the answer. But how?

Then Mountain Mike calls back. Mountain Mike, who found Foot Four and who's called Mountain Mike, he says, “because I can survive just about anywhere.” Which includes, apparently, an island in the Fraser River, alone, with only his dog, Sophie, for company.

The town of Ladner is a sloughy place south of Vancouver where farmland, sea, and suburb meet and where Mountain Mike comes in sometimes for a beer. “Ask him how many knives he's carrying!” the boys at Speed's Pub said when I went there looking for him. (One guessed five.) Now, as Mountain Mike motors toward me up the dead harbor, I can hear their laughter again, and I think, Uh-oh. Because now that I see Mountain Mike, he sure looks like he might be the One, with his crazy Taliban beard crawling up his face to meet his low-tugged camo hat, and his feral caterpillar eyebrows wrestling atop his nose.

A ginger dog bounds off the skiff to sniff my boots. “She's the one that found the foot,” Mountain Mike says. Not much of a retriever, he says. Won't touch dead things. She's left-handed, he adds. A real rat killer.

This seems like a lot of information. And very little. So I just nod and climb aboard.

As we head out of the slough, I take stock: I'm deepening my knowledge of missing and possibly murdered and dismembered citizens by heading out alone with a disheveled, knife-wielding stranger who looks and smells like a Sergio Leone villain.

But it's too late to turn back, so I decide to enjoy the morning sun, which is making the waters as bright as hammered sheeting, empty and beautiful. I comment on the river's beauty. Mountain Mike corrects me. There's crap all over the place, he says, pointing out a log off the port bow. Run into one of those babies at full speed and you can forget about it. Mike's 57, a lifelong fisherman, and he's helped fish out his share of watermen's bodies over the years.

“How many times have you seen shoes hanging on telephone wires? Did anyone ever look in those?”

We cross Ladner Reach, tie up at Kirkland Island, and hop onto an ATV. Mountain Mike is the caretaker of four islands clumped in the Fraser's south arm, a private bird-hunting preserve. While he drives, he talks about fishing, about birds, about trees. He pretty much talks the whole time.

The ATV rounds the northeastern tip of the island; the main channel of the Fraser, which bounds Kirkland Island's north side, swings into view. It's a good half-mile from our shore to the river's far shore: home to the city of Richmond. “They found the other foot right across the way there,” he says, pointing at a distant riprapped shore. Foot Seven, he means the last one found, and the one that matched Mountain Mike's Foot Four. It was picked up last November by a local politician's wife.

At a break in the trees, I stare hard at the Fraser's wind-scuffed water. Mountain Mike is right. It looks peaceful, but it's not, at all. The water is full of flotsam a deadhead nodding in a wave, a branch reaching up. Maybe the clue I'm supposed to absorb is that the bodies didn't necessarily come down the Fraser. They could've come from the Fraser.

I'm still a bit jumpy when we stop at a beach strewn with logs and matted canary grass. Here, Mountain Mike says, is where he stepped right on top of a woman's New Balance while out on one of his regular island walks. Sophie just kept staring at it, then back at him, then back at the shoe. “After the third time,” he says, “I knew this was something out of the ordinary.”

A coyote was following them that day, picking up the rats Sophie killed. I can't leave it here, Mountain Mike thought. He found a five-gallon bucket. Then he carried the foot all the way back across the island and rowed to town. For two hours, it was just the three of them: Mountain Mike, Sophie, and the foot.

After that, he says, Sophie changed for a long time. Wouldn't let people get near her. “She was really subdued. I don't know how they know.” I look at Sophie, worrying a stick on the beach. She seems better.

The foot rattled Mountain Mike, too, more than he thought it would. “It took me from May till September to come walk on these beaches,” he says. He's sitting on a driftwood log facing me now, smoking a hand-rolled cigarette. “I mean, you've found it, but you can't put the rest of it together. It's like when you get a craving for a chocolate bar, and you're in the middle of nowhere, and you don't have one, and there's like…a hole.”

I look at the man across from me. I don't see a knife-wielding loner anymore but one of the most thoughtful people I've met in a long time. I think that Mountain Mike is a good symbol for this entire Mystery of the Feet. He seems to be one thing in the imagination, but in reality he's something else entirely. And nothing to be frightened of.

What the Pig Knows

Why does a loose foot, or seven, skeez us out so badly? Why can't we shrug it off, let it sink back down and disappear, accepting the question mark?

Sinking is on my mind as I head up to see Gail Anderson. Gail is a renowned forensic entomologist who told me that, lately, her research has involved sinking dead pigs to the seafloor and watching what eats them.

This I really want to see.

Inside her office at Simon Fraser University, where she works in the School of Criminology, she presses some buttons on her computer and, through the magic of technology, we're 300 feet below the waters of Vancouver Island's Saanich Inlet. I watch as spot prawns mince across a pig carcass on delicate spot-prawn stilt legs. A squat lobster tears roughly at a jowl. I daydream about how delicious free-range, pork-fed lobster must taste. Anderson interrupts to say that, in three weeks, crabs and shrimp can reduce a 50-pound pig to a skeleton.

These experiments are showing Anderson what can happen to a body that, say, a bad guy sinks to the seafloor. But they're also a lesson in what nature can do on its own. And this is the point she wants to make when I ask about the feet: Nature can do weird-seeming stuff.

“Often, when we've found a body in the water, it looks like the guy has been through a terrible fight,” she says. “His knuckles can be all ripped up. His face can be ripped off. Your first thought is, My God, this guy's been through a helluva beating.” But that appearance can be caused by waves cheese-gratering the body against the bottom, she says.

Fair enough, you say. But if there's an answer for everything, why were the finds always feet? Well, our hands and feet are like kites, attached only by a few tendons. Underwater, they flap around and come off pretty easily when body tissues break down. Hands would dissolve and be eaten. Rubber-soled shoes would be natural flotation devices, and they would float sole up, protecting what's inside from gulls.

So why haven't we seen so much of this before? Well, in times past, leather and canvas shoes would disintegrate. Now the shoes survive.

Yeah, but this is seven freakin' feet. That doesn't sound a little odd to you?

Anderson shrugs as if to say, No, maybe it's not so odd after all. “I've spoken to a colleague in New Zealand who said, 'Oh, we get 15 feet in runners every year.'”

“How many times have you seen a shoe along a beach?” she asks. “How many times have you seen shoes hanging on telephone wires? Did anyone ever look in those?”

Closure Or Something Like It

I think I understand what Anderson is telling me: We are blind. We stumble through our world every day, unseeing, uncurious. Maybe we're just trying to keep it together and get the kids to soccer practice. We don't have time to look inside shoes on the beach. Then something happens. We look. And suddenly we see feet everywhere. And so we keep yearning to connect the dots. Even when we know that sometimes a foot is just a foot.

During one of my last afternoons in B.C., I meander in my rental car back to Westham Island. I turn onto a one-lane road that runs atop a dike over the Fraser, and I peer down, fascinated by the flotsam.

Ahead, an empty, wrecked shack slumps into the river. Time has flaked its fake red-brick siding. Driftwood shoals against its walls. And everywhere in the drain-clog-hair-mess of the scene there are reminders of a big river's appetite for junk: Quaker State bottles. A cooler. A crushed Bud can. A frayed bight of rope, coiled in the cattails like a serpent.

Then look! Right in the shack's window! A shoe! A boot! OK, actually sort of a low-cut boot thingy! Black, rubber. Sitting up on the shack's glassless wooden windowsill! My heart pole-vaults into my throat. I want to show somebody, but no one is around on this winter-bleak island. Somewhere, a dog barks. A boat's motor purls in the glassy channel.

It's definitely a man's boot. About a size 11, it looks like from here. And now I can see that the shack really isn't empty. Past the boot, where the underfed afternoon light hits the inside wall, something has been spray-painted that from up here looks an awful lot like is it? could it be? a smiley face.

My scalp crinkles electrically. My eardrums are pounding like a timpani. Then I'm heading down the embankment, laughing and terrified, to where the boot waits for me in the window as peacefully as a still-life in its weathered frame.

Correspondent Steven Rinella (@stevenrinella) is the author of American Buffalo: In Search of a Lost Icon (Spiegel & Grau), and author Christopher Solomon's (@chrisasolomon) work has appreared in The Best American Travel Writing series.