Iridescent Bones of a Lost Dinosaur Herd Discovered in an Opal Mine

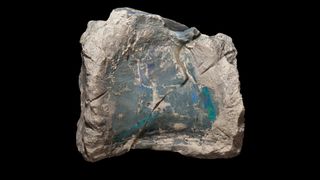

Gemstones are precious, especially when they come filled with dinosaur bones.

Back in the 1980s, a miner unearthed a slew of fossils preserved in opals in an opal mine near Lightning Ridge in Australia. A recent analysis of those opalized fossils revealed that they held the remains of a herd of dinosaurs — including the world's most complete opalized dinosaur. [Photos: Dinosaur Tracks Reveal Australia's 'Jurassic Park']

The fossils included parts of a previously undiscovered dinosaur species that is now named Fostoria dhimbangunmal after the opal miner Robert Foster who discovered the fossils back in the 1980s, according to a statement. The species name translates to "sheep yard" in local languages, which was given as a tribute to the opal field known as "Sheepyard," under which is the opal mine where the bones were discovered.

Though the fossils were discovered a couple decades ago, they weren't studied until recently when Foster's children donated them to the Australian Opal Center.

After the donation, a team of scientists at the University of New England at Armidale in Australia began to analyze them. They found bits and pieces of four Fostoria skeletons, some juveniles and some larger, likely adults that could have been 16.4 feet (5 meters) long when alive.

"We all assumed initially that this pile of bones was from a single individual, but it wasn't until I started piecing together the skeleton and examining each of the bones one by one that I realized something didn't quite fit," said lead author Phil Bell, a senior lecturer of paleontology at the University of New England. He realized the bones came from a herd or family when he identified parts of four different shoulder blades, from various-size animals.

"As a gentle herbivore, these dinosaurs didn't have much in the way of defence," Bell told Live Science. They didn't have sharp claws or horns, "so safety in numbers was probably their best bet."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This newfound two-legged species was related to Muttaburrasaurus, a plant-eating ornithopod dinosaur which was discovered decades ago in Queensland. "Most of the features that make Fostoria unique are quite subtle," Bell said. Indeed, it took many years to demonstrate that this was a new species of dinosaur, he said. But the team had in their hands a good part of a Fostoria skull, which is the "holy grail" for understanding what dinosaurs looked like, how they were related to other groups and what they ate, he added. (They can even look into the space where the brain would have been to figure out how the dinosaur perceived and smelled its world.)

Last year, the same group discovered another dinosaur preserved in opal in Lightning Ridge. They named that plant-eater, which also walked on two legs, the Weewarrasaurus pobeni. Lightning Ridge is the only place where opalized dinosaurs are found, Bell told Live Science previously.

These dinosaurs lived during the Cretaceous period when Lightning Ridge was a floodplain. Though most of the opalized fossils found in the area were from marine creatures that lived in the nearby sea, once in a while a bone from a land animal such as a dinosaur would wash out to sea and interact with silica minerals, according to the previous Live Science report. Silica minerals, the foundations of opal, would then build up in the cavities of fossilized bones or sometimes even seep into organic bones and form a replica of them.

"Without a doubt," Lightning Ridge still holds dinosaur fossils in its precious opals, Bell said. "The opal industry still thrives in Lightning Ridge, and where you find opals, you're just as likely to find fossils, too."

But these deeply buried fossil-holding opals aren't easy to get to, he added. So "it's really important to acknowledge the work of the miners, because without them we'd know nothing about this mysterious prehistoric world."

The study was published online June 3 in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.

- Photos: One of the World's Biggest Dinosaurs Discovered

- Photos: Spiky-Headed Dinosaur Found in Utah, But It Has Asian Roots

- Photos: Oldest Known Horned Dinosaur in North America

Originally published on Live Science.

Yasemin is a staff writer at Live Science, covering health, neuroscience and biology. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Science and the San Jose Mercury News. She has a bachelor's degree in biomedical engineering from the University of Connecticut and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.