Veteran U.S. show jumper Katie Monahan Prudent joined Chris Stafford on Stafford’s WiSP Sports Horse Show podcast on July 12 and gave a no-holds-barred opinion on the state of U.S. show jumping. Here’s a transcript of part of their interview:

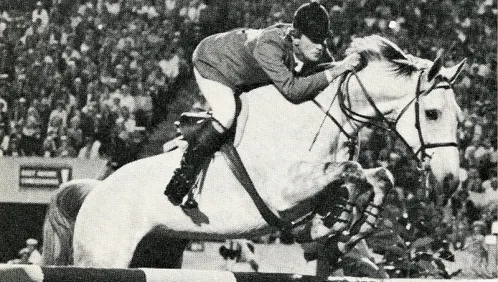

Chris Stafford: For more than two decades, Katie Monahan Prudent was one of show jumping’s most successful riders. In the first ever FEI World Cup Final, in Gothenburg, Sweden, in 1979, she finished second after tying for first place with Hugo Simon before losing a jump-off to him. She then went on to ride in five more Finals in the ‘80s. Katie dominated that decade of the ‘80s as few other riders have been able to do.

She was selected for the 1980 U.S. Olympic team but was denied the chance to compete because of the U.S. boycott. She was named the American Grandprix Association’s Rider of the Year three times in the ‘80s and awarded the Whitney Stone Cup for her superior record in international competition. As the Aachen [CHIO] gets underway this week, Katie will reflect on when she was a member of the gold medal-winning team there at the 1986 World Championships.

For many years, Katie has been a sought-after trainer who tells it like it is. And with a strong foundation in horsemanship, she now laments on how and why the sport has changed in the United States.

Katie, you’ve had so many top riders come through your hands in the course of your career, but it all began, of course, with the basis of a very successful career yourself. You are one of the most successful riders in the U.S., looking back on it, but it all began when you were very young, didn’t it?

Katie Prudent: I got into horses at a time in America that was unspoiled. Whoever rode in that age did it because they loved the horses. We loved to foxhunt, we loved to ride bareback, we loved to spend all day with the horses. Not just coaching has changed, but people have changed, the sport has changed. The idea of what a horse means in competition has changed.

I was very lucky to get into it at an age when I could enjoy everything about the horse and not be spoiled.

Stafford: It’s interesting that you say so many things have changed over time, some for the good and some things we’ve lost that really formed the basis of good horsemanship. Katie, when you look back at the benefits that you had from growing up in that era of the sport and what might be missing now, that informs you as a coach to adjust with those things in mind. I’m interested in that transition.

Prudent: For example, in America now, in competition, there are levels of competition that start at 80 centimeters. I’m thinking of jumpers, not hunters. They start at the lowest level. As George Morris would say, it’s practically subterranean. And it’s true!

When I was a kid, you did junior hunters, and that was 3’6″, which is a little more than a meter. And if you wanted to do jumpers, you did the junior jumpers. But there was not low children’s jumper, children’s jumper, modified children’s jumper, low junior jumper. The way it’s been dummied down in today’s world, it’s amazing that anyone can ride at all. The sport has become for the fearful, talentless amateur. That’s what the sport has been dummied down to.

Unfortunately, because of money, the fearful, talentless amateur can rise to a certain level. And that’s sort of what the sport has become—how far can the amateur go by buying the greatest horse in the world. It’s not where can a good riding kid go on any horse that comes down the pike. It’s just a totally different sport now.

And many coaches have become coaches who just bring along amateur riders and make it easy for them. “Oh baby, here’s a bottle of water. Are you too hot? Are you too cold? Let’s get a fan. Let’s get someone else to ride your horse because it’s too difficult.” It’s just become a sport for rich, talentless people. And I don’t coach like that. I’m a mean teacher.

I make those kids work hard. If they sass me, I take those stirrups off. I still teach like I grew up, where I want the riders to be tough and to appreciate the horse and to learn how to ride every problem. In today’s world, the trainers take away the problems. They don’t want the riders to have a problem. Every horse has to go out of the barn with earplugs in, so that they don’t hear or look or spook at anything.

The sport makes me sick nowadays. And in America, what’s very sad is that we’re not producing a ton of great riders. We have all the Irish boys coming over here and riding all the horses and getting all the owners. Because we’re just producing a bunch of weak amateurs.

Stafford: How do you think this effect started to happen and pick up momentum? To undermine horsemanship in this country, to—if you will—mollycoddle the riders and for this culture among trainers to buy into it, the parents too. How did this start, and why do you think it kept up the momentum that is has and taken over the sport to the extent that is has done?

Prudent: I remember many, many years ago, we went to France to show. I probably was just dating my husband or we’d just met. When we went to France, the dollar was 10 to 1 on the French franc. So a great horse from France, and there were many great horses in those days in France, priced in French francs was 1/10 in dollars. So for a short time, horses could be bought in Europe for incredibly good prices. And people came from Europe with great horses, and then all of the sudden everybody started shopping in Europe.

ADVERTISEMENT

If you had an amateur rider or a junior rider, you got on a plane and went to Europe to find a horse. For about a decade it was like that. I think in the beginning, it was because the prices were so good. And as it evolved, it became clear that bad amateur riders who had a lot of money could buy really good horses and compete with the professionals. I think over time, especially in America—I’m not even going to say in the rest of the world, even though I have to say the rest of the world is catching up to us now—rich parents saw a way to buy their children success.

One thing led to another, and now we’re in a terrible place.

Stafford: And do you see a way out of this trough now, to pull us out of this and produce the riders that we need for international success?

Prudent: I don’t see a way out right now. I think we’re going to have to hit rock bottom. And the team and all of us are talking about it, and how to get us out of it. But I think in about five to 10 years, we’re going to have a very hard time putting together a good team. I really think we are.

Stafford: It really is a sad situation when you look at it in terms of the U.S.’s position in the international sport.

Prudent: I agree. You know, you look at McLain [Ward], who was the son of a dealer and had a lot of hard times with family problems. You look at Kent Farrington, who was a boy who didn’t have a lot of money and worked for a lot of different people like Leslie [Howard] and Tim Grubb and came up through the ranks just really working hard. And Laura Kraut, who rode anything and everything that came down the pike. And she still can get on any horse and make it go well.

We just don’t have those riders coming along anymore. We just don’t. Beezie [Madden], when she started working with John [Madden] and doing all his sales horses, she also can ride any type of horse and turn it around to go her way. Those are our four top riders right now, and they’re always the four top riders for the last decade.

Once they’re gone, I don’t know what we’re going to have.

Stafford: What about that next tier down; I’m thinking of Reed Kessler, Jessica Springsteen, Katie Dinan. There’s a whole tier of these younger girls, some of whom have gone through your hands as well.

Prudent: They all have great basics. They’re all very good riders. But they have all, the ones you’ve named, only ridden the best horses money can buy. In their lives, from the time they were little children, they have only ridden the best horses that money can buy.

That’s how you can’t compare them to a McLain or a Kent or a Beezie. You can’t compare them.

Stafford: So what happens when they run out of good horses? Does that ever happen, do you think, or have we developed a culture now where we won’t allow that to happen because we need them on the team for future generations?

Prudent: Well, it depends on how much money they have, right?

Stafford: Let’s talk about the trainers themselves, the coaches. They are feeding into the culture that you’re talking about, Katie, by enabling the owners, the parents, to buy these expensive horses. The athlete, the rider themselves, doesn’t have to have the responsibility. They’ve got someone to blame if the horse doesn’t go well—they can blame the coach.

Prudent: Yeah. And the coaches have learned to try and make it easy for the riders. They want their riders to like the sport. They want their riders to stay with them. They want it to be a nice day at the horse show.

You know what? It isn’t always a nice day at the horse show. Sometimes you have to work really hard to get through a day, and a lot of these kids, they don’t even know what that means.

ADVERTISEMENT

Stafford: Another thing we don’t see in the hunter/jumper world is that the trainers don’t encourage the young riders who are taking up the sport or getting a horse, they don’t want them in the barn, to spend time in the barn, to learn the basics of horsemanship. How do we stop that decline?

Prudent: I don’t know. Years ago—I’m not even going to mention the rider’s name—one girl rider had had a bad day, and the trainer wanted that rider to ride another horse and maybe work without stirrups. To pay her dues.

And the barn manager said, “Oh no, she has an appointment to go get her nails done.” I have to tell you, that is America in a nutshell right there. That is where we’re going in our sport in America. It makes me sick. And I don’t know a way out of it.

Stafford: There doesn’t seem to be an easy solution. Obviously, the top riders will always be the role models for the younger generations to come. Do you see the level of dedication amongst younger riders who come through your hands now? Is there a willingness to learn the basics, the foundation, to do the hard slog to be the rider they need to be? Or are they just talented because they have the top horses money can buy?

Prudent: I have to say that most of the riders whose families have a lot of money, they don’t have the same desire to work at their sport as the kids who grew up without money. I guess that’s maybe the same in everything; I don’t know. But I see it as a problem.

Stafford and Prudent’s conversation continued, touching on the topics of the cultural differences between the U.S. show jumping and the one in Europe, the need for the sport to stand up to animal rights activists, and more. To hear the interview in its entirety, listen to the podcast:

Stafford finished the podcast with:

Stafford: I’m going to ask you finally what you value most about spending a life in horse sports?

Prudent: I most value the love of the animal. I just love horses. I ride every day, and I just love to train horses. I love to take an animal whose natural instinct, when he’s afraid, is to run away, and make him so confident and loving that he’ll do whatever I ask him to.

Stafford: And if you had to give a message to young girls listening to this program about coming into the sport and how to educate themselves for a career in horses, what would you say?

Prudent: I think that with whatever horse they’re lucky enough to ride, their goal should be to get a communication with that horse to have the ability to make that horse do whatever they ask it to do. We get away from that in people who buy horses for high prices. They think horses should just do it for them, because they paid a lot of money. When actually, their communication with the animal and relationship with the animal is what can bring success.

And so to any young rider coming into the sport, I would say, “You get on that horse, and through a long time, spending hours with the horse, getting a good education in basics—how to use your leg, how to use your reins—see if you can take that animal and get him to do what you want to do.

And join the discussion on the Chronicle’s discussion forums.

This podcast and transcription kindly shared by permission of The Horse Show Podcast, a WiSP Sports Production—episodes are available at www.wispsports.com.