I started riding when I was 6. For many years, my riding dreams were simple: to love horses, be a good rider, and enjoy being competitive at the local shows my barn frequented. My horse world and knowledge of the show world were naïve and uncomplicated.

When I was in junior high, I started receiving compliments about my riding, and some people told me I should do the ASPCA Maclay Finals. I didn’t really know what the Maclay was, but I understood enough to know it was a compliment. During that timeframe, some of the girls in my barn began frequenting the local A shows, and I added showing at St. Louis National Charity (Missouri) as a goal. This was back in the day where rated shows still held an aura of prestige, and since the Charity was the show in St. Louis, it felt like a reputable goal—one I accomplished around the age of 14 in the pony jumpers. I still treasure the second-placed ribbon we won in the Marshall & Sterling Classic, though at the time I was so new to rated shows I didn’t really know what a “classic” was—too bad, because I haven’t had an opportunity to wear whites since!

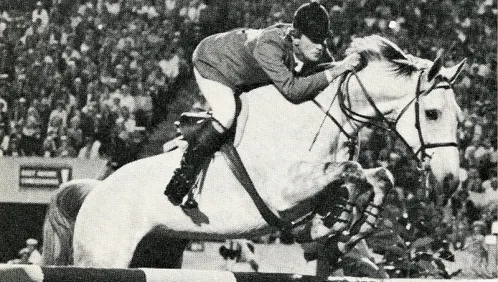

In high school, I became acutely aware that there was a broader rated show world beyond the local pond that remained mostly out of my reach. I watched the big jumper classes at the rated shows in Lake St. Louis (Missouri) and dreamed of someday being a legit jumper rider. But this was pre-social media, so it wasn’t until “Horse Power: Road to the Maclay” launched in 2006—the year after I graduated high school—that the true extent of the elite rated-competition scene hit me.

After watching the show, I instantly felt like I had missed the train. There weren’t just $25,000 regional grand prix classes—there were $100,000 or even $1,000,000 classes. There was Maclay Finals and Medal Finals and the Winter Equestrian Festival (Florida) and indoors and Devon (Pennsylvania) and Upperville (Virginia).

Overnight things had changed. In my mind, now my riding successes could only be compared with winning at the top levels. In that light, I felt like my years of riding and showing had fallen short.

I hadn’t just missed doing the Robert Murphy show in Kentucky each summer (which our barn attended but we couldn’t afford); I had missed being a Big Eq rider. And that, I had learned, is the pathway to being a legitimate U.S. rider. Internally, my honed horsemanship skills or ability to flat a horse correctly or experience with off-the-track Thoroughbreds and greenies and problem horses or avid consumption of all the right books felt meaningless alongside the absence of an impressive rated show ring resume.

Growing up in the St. Louis local horse show scene, Jennifer Baas never knew there was an extensive A circuit until she was exposed to the TV show “Horse Power: Road To The Maclay.”

As a result, I remember feeling so much more pressure to be something great, because I felt I had to compensate for all that I lacked. That feeling whispered (or yelled, mostly) in my ear during my stint as a professional, which ended somewhat forcibly at age 25. It took years to begin accepting my place in the sport and not see where I was as a failure but as a gift. And it took until last fall—after 15 years of feeling like a nobody—to finally feel a true competence, confidence and happiness in my riding regardless of outward success—something I honestly hadn’t felt since I was an oblivious kid.

Don’t get me wrong, I still have moments of biting regret and a deep sense of failure when I let the thoughts of what I should, could or wish I had been creep in—usually when watching live feeds of indoors or finals. But mostly I’ve learned to accept myself for all that I am and all that I’m not and to let that be enough—to recognize that I don’t need an A show resume to tell me I’m a good rider. I can nod to all the skill seen in the show rings and also nod to my own skills, which are usually seen only by the cyclists who pass by my arena.

ADVERTISEMENT

Because here’s the thing: As I’ve taken time to step back and evaluate what it takes to be successful at the top level, I see the sport through the lens of my 10-year-old self again. Back when what was most important was whether my pony was happy and whether I did a good job. Back when I gladly stayed home from a highly-anticipated show because my pony got hurt the night before. Back to when I had a very cool but incredibly sensitive OTTB who needed everything “just so,” who made me learn about saddle fit and farriery and diet and how to sit a spectacular rear.

Back to true horsemanship: putting the horse first. Truly and wholly first.

Which I’ve realized is something most people claim to do but sadly don’t execute at the top levels just as much as at the bottom. And the result is a sport that seemingly tolerates poor horsemanship and bad ethics even at the most elite levels. Levels which should be an example of the highest standard of riding and horsemanship.

I have to be honest, seeing so many stories of poor horsemanship being rewarded, of cheaters getting away through loopholes, of drugging and “prep” practices that are “legal” only because they won’t test or aren’t specifically against the rules (though certainly violating the spirit of the rules), of big-name trainers who have gotten away with abusing women or teens, of hearing first-hand stories of BNTs who are known to “like them young,” of seeing a sport that has developed into rewarding those who can show the most at whatever the cost to the horse, of a sport where one must show 75 percent of the year to be competitive on the big scale.

It’s not a sport I really ache to be a part of anymore. And I have a feeling there’s a lot of you out there who feel similarly. What does it say when I sit with my talented, brave amateur friends watching a big grand prix, shaking our heads saying, “I don’t even want that any more. It’s not worth it.”

And truly, I love competition. I love seeing where my horse and I stack up. I love getting recognized for all the hard work, blood, sweat and tears put into it. I love the shot at a year-end award. I love the camaraderie with fellow riders as we share beers while cleaning stalls after a long day of showing.

But I find my desire to be a part of the A show scene dwindling—a scene that defined my insecurities for so long—and not just because of the exorbitant expense, but because of its culture of silent complicity in the face of a lot of unacceptable practices.

Now I can hear you saying, “But, Jen, I see bad horsemanship and bad ethics at the bottom of the sport too.” Yes, you’re right, and it’s unacceptable at any level, though I would maintain that the top of the sport should be an example to the bottom and greater burden of excellence put upon those who are the face of the elite levels.

ADVERTISEMENT

I can also hear you saying, “But, Jen, there’s great horsemanship and great riding at the top of the sport; it isn’t all bad.” And I agree wholeheartedly. There are incredible riders and excellent horsemen at the elite levels, and I admire many of them. But what’s sad is that today’s sport admires the result regardless of the process. The good eggs are just as accepted, lauded and celebrated as the bad ones, many of whom are defended and legitimized simply because they have attained “BNT status.” This cheapens the value of the excellent horsemen and riders who do exist.

So I suppose my question is, why are all of us at the bottom fighting so hard to be a part of a show scene that, if we step back and really evaluate, isn’t really what we want or support?

Why do we internally devalue our own horsemanship and riding skills just because they’re not seen under the trees at Upperville? Why do we allow the elite A sector to make us feel “less than” because we’re trail riding on a Sunday instead of wearing whites?

I care the most about being a truly great horsewoman who makes decisions for the best of the horse first and for me second. I care about being an educated, soft, thoughtful rider, about my horses progressing and developing in a correct manner.

And I no longer need A show results to validate whether I am those things—and neither do you.

So let’s be less concerned with affording the elite levels and more concerned with creating a sport we’re proud of. Alongside accessibility, let’s make clean and honest sport hallmarks of our battle cry. Let’s see silence and feigned ignorance for what they are: complicity. Let’s work to create a culture that harkens back to how so many of us lived and breathed as children, when our love of horses was first, our enjoyment was paramount and our desire for sport simply an outflow of those characteristics.

Let’s stop defining ourselves by whether we can “make it to the top” and simply remain obsessed with being excellent horsemen, giving power not to awards or accolades but to how we’re seen through the eyes of our horses.

Let’s empower and inspire each other instead of settling. Let’s stop playing the game and instead reinvent it. To paraphrase Gandhi, let’s be the sport we wish to see instead of becoming the sport that’s in front of us.